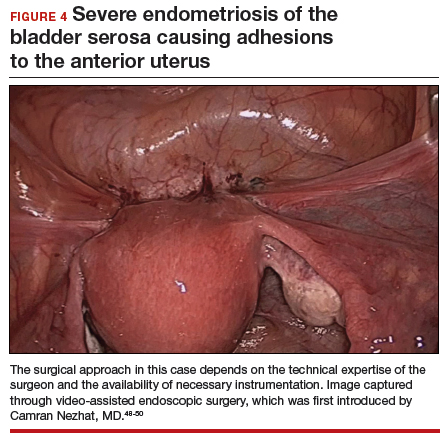

Bladder endometriosis. Surgical treatment for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and the location of the lesion (FIGURE 4). Lesions of the superficial aspect of the bladder identified at the time of laparoscopy can be treated with either excision or fulguration28,35,44 In our group, we perform excision over fulguration to remove the entire lesion and obtain a pathologic diagnosis. Deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle are likely to be an endometrioma of the bladder. In these cases, laparoscopic excision is recommended.7 Rarely, lesions close to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy.19,45

In our experience, laparoscopic resection of bladder endometriomas is associated with better results in terms of symptom relief, progression of disease, and recurrence risk compared with other approaches. When performing laparoscopic excision of bladder lesions, we concomitantly evaluate the bladder lesion via cystoscopy to ensure adequate margins are obtained. Double-J stent placement is advised when lesions are within 2 cm of the urethral meatus to ensure ureteral patency during the postoperative period.45 A postoperative cystogram routinely is performed 7 to 14 days after surgery to ensure adequate repair prior to removing the urinary catheter.9,25,46,47

Postsurgical follow-up

Follow-up after treatment of genitourinary tract endometriosis should include monitoring the patient for symptoms of recurrence. Regular history and physical examination, renal function testing, and, in some instances, pelvic ultrasonography, all have a role in surveillance for recurrent ureteric disease. IVP or MRI may be warranted if a recurrence is suspected. A high index of suspicion should be maintained on the part of the clinician to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss. Patients should be counseled about the risk of disease recurrence, especially in those not undergoing postoperative hormonal suppression.

In conclusion

While endometriosis of the genitourinary tract is rare, patients can experience significant morbidity. Medical management of the disease is often limited by substantial adverse effects that limit treatment duration and is best used postoperatively after excision. An adequate physical exam and preoperative diagnostic imaging can be employed to characterize the extent of disease. When extensive disease involving the ureter is suspected, preoperative consultation with a urologist is encouraged to plan a multidisciplinary approach to surgical resection.

The ideal approach to surgery is laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance. Treatment of ureteral disease most commonly involves ureterolysis for cases of extrinsic disease but may require total resection of the ureter with concurrent ureteral reconstruction when disease is intrinsic to the ureter. Surgery for bladder endometriosis depends on the depth of invasion and location of the lesion. Superficial bladder lesions can be treated with fulguration or excision, while deeper lesions involving the detrusor muscle require excision. Lesions in close proximity to the interureteric ridge may require ureteroneocystostomy. Follow-up after excisional procedures involves monitoring the patient for signs and symptoms of disease recurrence, especially in cases of ureteral involvement, to avoid the devastating consequences of silent kidney loss.

The definitive cause of endometriosis remains unknown, but several prominent theories have been proposed.

Sampson's theory of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes is the most well-known theory,1 although Schron had acknowledged a similar thought 3 centuries before.2 This theory posits that refluxed endometrial cells enter the abdominal cavity and invade the peritoneum, developing a blood supply necessary for survival and growth. Early reports supported this theory by suggesting that women with genital tract obstruction have a higher incidence of endometriosis.3,4 However, it was later confirmed that women without genital tract obstruction have a similar incidence of retrograde menstruation. In fact, up to 90% of women are found to have retrograde menstruation, but only 10% develop endometriosis. This suggests that once endometrial cells have escaped the uterine cavity, other events are necessary for endometrial cells to implant and survive.3,5 Other evidence to support the theory of retrograde menstruation is the observation that endometriosis is most commonly observed in the dependent portions of the pelvis, on the ovaries, in the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and on the uterosacral ligament.6

The coelomic metaplasia theory holds that endometriosis results from spontaneous metaplastic change to mesothelial cells derived from the coelomic epithelium (located in the peritoneum and the pleura) upon exposure to menstrual effluent or other stimuli.7 Evidence for this theory is supported by the observation that intact endometrial cells have no access to the thoracic cavity in the absence of anatomical defect; therefore, the implantation theory cannot explain cases of pleural or pulmonary endometriosis.

Immune dysregulation also has been invoked to explain endometriosis implants both inside and outside the genitourinary tract. Studies have shown a higher incidence of endometriosis in women with other autoimmune disorders, including hypothyroidism, chronic fatigue syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, and multiple sclerosis as well as in women with allergies, asthma, and eczema.8 In such women, dysregulation of the innate and adaptive immune system might promote the disease by inhibiting apoptosis of ectopic endometrial cells and by promoting their attachment, invasion, and proliferation into healthy peritoneum through the secretion of various growth factors and cytokines.9,10

Other possible theories that might explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis exist.11-13 While each theory has documented supporting evidence, no single theory currently accounts for all cases of endometriosis. It is likely, then, that endometriosis is a multifactorial disease with a combination of immune dysregulation, molecular abnormalities, genetic and epigenetic factors, and environmental exposures involved in its pathogenesis.

References

- Sampson J. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-469.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, et al. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:151-154.

- Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG, Schikler KN, et al. Endometriosis in association with uterine anomaly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39-43.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Vercellini P, Chapron C, Fedele L, et al. Evidence for asymmetric distribution of lower intestinal tract endometriosis. BJOG. 2004;111:1213-1217.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, et al. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2715-2724.

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1-10.

- Sidell N, Han SW, Parthasarathy S. Regulation and modulation of abnormal immune responses in endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955: 159-173; discussion 199-200, 396-406.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013;252-258.

- Buka NJ. Vesical endometriosis after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1117-1118.

- Price DT, Maloney KE, Ibrahim GK, et al. Vesical endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Urology. 1996;48:639-643.