What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

First, some cognitive decline is expected at midlife based on increasing age. Second, above and beyond the role of chronologic aging (ie, getting one year older each year), ovarian aging plays a role. A role of estrogen was verified in clinical trials showing that memory decreased following oophorectomy in premenopausal women in their 40s but returned to presurgical levels following treatment with estrogen therapy (ET).17 Cohort studies indicate that women who undergo oophorectomy before the typical age of menopause are at increased risk for cognitive impairment or dementia, but those who take ET after oophorectomy until the typical age of menopause do not show that risk.18

Third, cognitive problems are linked not only to VMS but also to sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and increased anxiety—all of which are common in midlife women.15,19 Lastly, health factors play a role. Hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and smoking are associated with adverse brain changes at midlife.20

Giving advice to your patients

First, normalize the cognitive complaints, noting that some cognitive changes are an expected part of aging for all people regardless of whether they are male or female. Advise that while the best studies indicate that these cognitive lapses are especially common in perimenopausal women, they appear to be temporary; women are likely to resume normal cognitive function once the hormonal changes associated with menopause subside.15,16 Note that the one unknown is the role that VMS play in memory problems and that some studies indicate a link between VMS and cognitive problems. Women may experience some cognitive improvement if VMS are effectively treated.

Advise patients that the Endocrine Society, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), and the International Menopause Society all have published guidelines saying that the benefits of HT outweigh the risks for most women aged 50 to 60 years.21 For concerns about the cognitive adverse effects of HT, discuss the best quality evidence—that which comes from randomized trials—which shows no harmful effects of HT in midlife women.5-7 Especially reassuring is that one of these high-quality studies was conducted by the same researchers who found that HT can be risky in older women (ie, the WHI Investigators).5

Going one step further: Protecting brain health

As primary care providers to midlife women, ObGyns can go one step further and advise patients on how to proactively nurture their brain health. Great evidence-based resources for information on maintaining brain health include the Alzheimer’s Association (https://www.alz.org) and the Women’s Brain Health Initiative (https://womensbrainhealth.org). Primary prevention of AD begins decades before the typical age of an AD diagnosis, and many risk factors for AD are modifiable.22 Patients can keep their brains healthy through myriad approaches including treating hypertension, reducing body mass index, engaging in regular aerobic exercise (brisk walking is fine), eating a Mediterranean diet, maintaining an active social life, and engaging in novel challenging activities like learning a new language or a new skill like dancing.20

Also important is the overlap between cognitive issues, mood, and alcohol use. In the opening case, Jackie mentions alcohol use and social withdrawal. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), low-risk drinking for women is defined as no more than 3 drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week.23 Heavy alcohol use not only affects brain function but also mood, and depressed mood can lead women to drink excessively.24

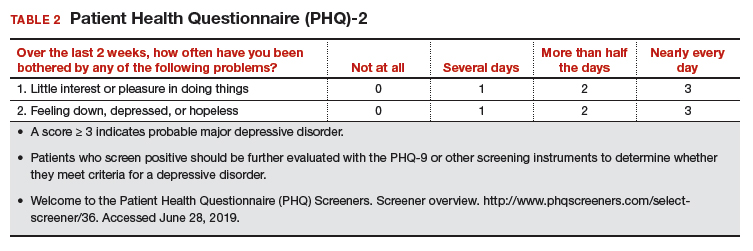

In addition, Jackie’s mother has AD, and that stressor can contribute to depressed feelings, especially if Jackie is involved in caregiving. A quick screen for depression with an instrument like the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; TABLE 2)25 can rule out a more serious mood disorder—an approach that is particularly important for patients with a history of major depression, as 58% of those patients experience a major depressive episode during the menopausal transition.26 For this reason, it is important to ask patients like Jackie if they have a history of depression; if they do and were treated medically, consider prescribing the antidepressant that worked in the past. For information on menopause and mood-related issues, providers can access new guidelines from NAMS and the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC).27 There is also a handy patient information sheet to accompany those guidelines on the NAMS website (https://www.menopause.org/).

Continue to: CASE Resolved...