This cephalad apical attachment can be accomplished in a variety of ways, by suspending the vaginal apex from the uterosacral ligaments, from the sacrospinous ligament, or via abdominal sacrocolpopexy.

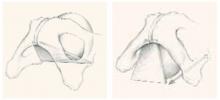

FIGURE 1 Anatomy of the anterior wall

The anterior vaginal wall resembles a trapezoidal plane, with ventral and more medial attachments near the pubic symphysis, and dorsal and more lateral attachments to the ischial spine. Detachment from the pelvic sidewall and ischial spine results in anterior wall prolapse (right).

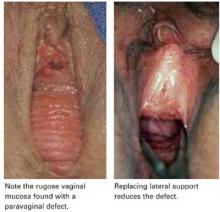

FIGURE 2 Paravaginal defect

FIGURE 3 Transverse defect

A transverse defect with loss of the anterior fornix. The loss of cephalad apical attachment at the level of the ischial spine leads to anterior wall prolapse. Suspending the upper vagina from shortened cardinal/uterosacral ligaments, the sacrospinous ligament, or via abdominal sacrocolpopexy is as important as plication.

Symptoms of anterior wall prolapse

As with other forms of pelvic organ prolapse, many patients complain of a bulge or feeling of pelvic pressure when the anterior vaginal wall has come through the introitus. However, some symptoms of anterior wall prolapse are unique.

Incontinence is not universal. A common misperception is that most patients with cystocele also experience stress urinary incontinence (SUI), which can develop when there is loss of urethral support and descent of the lower vaginal wall along with urethral hypermobility. However, there is no defining degree of hypermobility that links anterior wall prolapse with SUI. That is because the continence mechanism relies not only on urethral position and lateral attachments, but also on the neuromuscular function of the pelvis and lower urinary tract.

In fact, descent of the midvagina under the bladder base may actually reduce the chance of SUI. The reason: As a woman strains, the increased abdominal pressure pushes the cystocele farther and farther out. As the cystocele enlarges, it creates a functional outlet obstruction by kinking the urethra shut. When this is the case, patients may complain of prolonged voiding, an intermittent urine stream, and/or urinary retention. The woman may have to elevate the vaginal wall to empty her bladder. Patients with chronic urinary retention are at risk of developing recurrent urinary tract infections.

Bladder outlet obstruction and detrusor dysfunction. Women with grade 3 or 4 cystoceles often have evidence of bladder outlet obstruction on urodynamic testing, according to a study that found such evidence in 57% of subjects.5 After reduction of the prolapse with a pessary, obstructed flow reverted to normal in 94% of these women.

A large proportion (52%) of women with cystoceles also have detrusor instability, as well as evidence of impaired detrusor contractility. Many complain of urinary frequency and urgency and difficulty emptying the bladder.5

Again, this phenomenon is complex, related not only to anatomy but to altered neuromuscular function of the lower urinary tract. Incomplete emptying, frequency, and urgency may arise from stretching of the bladder base as it prolapses through the vaginal introitus, resulting in urinary retention. These symptoms often are less pronounced at night when the patient is supine.

We reviewed 35 cases of anterior wall prolapse greater than 1 cm outside the hymen, with elevated postvoid residuals exceeding 100 cc on 2 separate occasions.6 Thirty-one (89%) had normal postvoid residuals following reconstructive surgery and correction of their anterior wall prolapse.

Preoperative assessment

A careful physical exam is a prerequisite for all surgical repairs of pelvic organ prolapse. During this exam, identify the sites of defects and detachments.

Maximize the defect. Have the patient perform the Valsalva maneuver, cough, and/or strain while sitting upright or standing. As she is performing these maneuvers, ask her if this feels like her maximum prolapse. A split speculum often aids in visualizing the anterior and posterior compartments without pressure from the opposite vaginal wall.

Assess the apex. Place a large swab in the vagina, hold it gently against the apex, and ask the patient to strain. If the swab is pushed out, the apex needs suspension.

This technique can help identify apical relaxation that may be masked by a large anterior or posterior wall defect. A standardized staging system, such as the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantitative Examination (POP-Q) or Baden-Walker, aids in communicating and documenting the prolapse. In addition, it allows the surgeon to track anatomical outcomes after surgery.

Look for paravaginal defects by supporting the lateral anterior walls with a ring forceps at the level of the ATFP. Barber et al7 found this maneuver to be highly sensitive (90–94%): If no paravaginal defect was suspected clinically, none was found intraoperatively. However, the positive predictive value was poor (57%), in that defects suspected preoperatively were confirmed during surgery in less than two thirds of patients.