These findings point to the importance of careful intraoperative assessment, both before and during the repair procedure.

Limited utility of imaging studies. The use of radiologic studies such as defecography or dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis may aid in the evaluation of defecatory disorders or suspected sigmoidocele or rectal prolapse, but have not been studied sufficiently to determine the impact on surgical outcome.

Unmasking SUI

As mentioned above, women with anterior wall prolapse do not always complain of stress incontinence. However, correction of the cystocele can relieve their obstructive voiding and unmask “occult” SUI. Various techniques have been described to elevate the anterior wall with pessaries, swabs, etc, during urodynamic testing to predict which women should have an incontinence procedure performed at the time of reconstructive surgery.

Conflicting rates of occult SUI have been reported, with estimates ranging from 36% to 80%.8 Although preoperative urodynamic testing indicates a high rate of occult stress incontinence, a study by Borstad et al9 suggests that the rate of de novo incontinence may be lower and that preoperative urodynamic findings are not predictive of postoperative continence status. In that study, 16 of 73 women (22%) developed stress incontinence following surgery for prolapse when no incontinence procedure was performed. Advanced age increased the risk of incontinence after surgery.

Contrast these findings with those of Chaikin and colleagues,10 who prospectively followed 24 patients with grade 3 or 4 cystoceles. Preoperative urodynamics showed a 58% rate of occult stress incontinence. All these patients were also defined as having intrinsic sphincter deficiency with leak point pressures below 60 cm water. The incontinent group underwent anterior colporrhaphy and concomitant pubovaginal sling, compared with anterior colporrhaphy alone for those without incontinence. Postoperatively, 2 patients who had the pubovaginal sling procedure reported continued stress incontinence (14%). No new symptoms of incontinence were reported in the patients without leakage on preoperative urodynamics. Thus, preoperative urodynamics were 100% accurate in determining which women did not need additional surgery for SUI.

Implications of a negative stress test. Our experience has shown that, despite our best attempts, a negative stress test with the prolapse reduced prior to surgery is less than 100% predictive. Occasionally, new SUI occurs after reconstructive surgery. It is unclear whether this incontinence is caused by straightening the urethra and reducing the bulge or secondary to the dissection of surgery.

Tips on technique

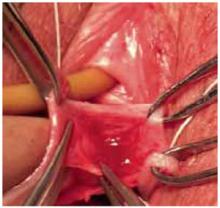

Anterior colporrhaphy traditionally is performed with plication of the “endopelvic fascia” or fibromuscular layer at the bladder neck with a Kelly plication stitch. Using “3-point” traction aids in dissecting the muscularis (FIGURE 4). Repair the remainder of the cystocele using vertical mattress stitches (1 or 2 layers) from the bladder neck to the apex.

Avoid creating weak areas. Using this technique, the repair frequently stops short of the apex, leaving a “gap” or weak area. One way to avoid this is to begin plication at the apex instead of the bladder neck (FIGURE 5).

Next, excise the excess vaginal tissue and close with interrupted fine absorbable sutures (FIGURE 6).

Recreate apical support. Another problem with traditional repairs is that they do not reestablish apical support. In many patients with anterior wall prolapse, reattachment of the apex reduces the cystocele. Therefore, it often is necessary to combine anterior colporrhaphy with an apical repair procedure such as uterosacral ligament suspension or sacrospinous ligament suspension.

Sutures for the apical repair should be placed and held prior to initiating the anterior colporrhaphy. At the end of the anterior repair, incorporate the apical sutures into the vaginal cuff.

Careful attention to the integrity and strength of the tissue is crucial. Regardless of the type of transvaginal suspension, we advocate bringing 1 arm of the suspension suture through the anterior wall of the cuff. Then place the other suture arm through the posterior cuff so that, when tied, anterior and posterior walls are brought together and suspended.

Using prolonged-delayed absorbable suture allows for a full-thickness bite, ensuring scarring to the suspensory ligament. If permanent suture is used for the uterosacral suspension, place the stitches along the inside surface of the anterior wall with a strong, broad bite that incorporates the muscularis or “endopelvic fascia.”

The occasional enterocele. When a transverse cystocele occurs following hysterectomy, the surgeon should be on the lookout for an enterocele, which sometimes accompanies anterior wall prolapse. The enterocele should be corrected at the time of surgery by closing the defect and suspending the cuff.

FIGURE 4 Three-point traction

Three-point traction using Allis clamps. The assistant retracts with DeBackey forceps to allow dissection of the muscularis. An index finger placed firmly against the vaginal mucosa enables the surgeon to judge depth of dissection.