Surgical exploration of the plexus is often advised when biceps muscle function is absent at 3 months of age. Some surgeons recommend waiting until 9 months before pursuing surgical exploration.10 No randomized trials have been performed demonstrating the value of surgical intervention, but case series report that surgical intervention with nerve grafting or nerve transfer is superior to management without neurosurgery.

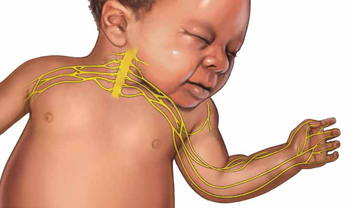

The consequences of permanent OBP injury

A lifetime of corrective therapy for the child. OBP injury may result in a permanent brachial plexus injury—permanent arm weakness requiring decades of physical therapy and multiple surgeries to try to reduce functional disabilities. Problems that frequently occur in children with OBP injury include:

- shoulder contractures

- limb length differences

- winged scapula

- behavioral and developmental problems.

A patient’s care may be coordinated at a brachial plexus injury specialty center, where coordinated access to pediatric neurologists, neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and neurophysiologists is available and physical and occupational therapy are provided.

Years of emotional response for the parents. Following a birth complicated by shoulder dystocia, the parents may experience grief and anger. During the decades following the birth, the parents of the child will wonder if the injury could have been avoided. They may be asked by friends and relatives, “Would a cesarean delivery have prevented the injury?” Physical therapists, pediatric neurologists, orthopedic and neurosurgeons may reinforce the idea that the injury was caused when the obstetrician applied excessive lateral force to the head and neck, resulting in an injury to the brachial plexus.

Decades-long exposure to these ideas, unresolved anger, financial stress, and lingering doubts may result in the parents and child pursuing civil litigation against the delivering clinician.

Can we reduce the incidence of OBP injury and our risk of litigation?

There are no interventions proven to reduce the incidence of OBP injury. However, many experts advise that a multifaceted approach to this obstetric emergency may reduce the incidence of severe OBP injury at the same time that we reduce our risk of litigation.

When counseling patients about the risk for OBP injury, use teach-back. Patients tend to misunderstand or forget much of what their clinicians teach them.11 Teach-back is an iterative communication process in which the clinician teaches the patient a concept or technique, then asks the patient to repeat the concept in their own words or demonstrate the technique. The clinician then amplifies the concept or technique and corrects misunderstandings. The patient is then asked to repeat the concept or demonstrate the technique. When using teach-back, the clinician never asks, “Do you understand?” The clinician encourages the patient to teach the concept to the clinician using the patient’s own words.12

In the case above, the patient has multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia, including obesity, short stature, insulin-treated gestational diabetes, and a large fetus. Given the high risk for shoulder dystocia, teach-back might help the patient better understand the situation. After explaining the concepts to the patient, the teach-back questions to the patient might include:

- “Can you tell me what is a shoulder dystocia?”

- “Can you list the health conditions that you have that increase your baby’s risk of shoulder dystocia?”

- “When a shoulder dystocia occurs, what actions will we take at birth to try to fix the shoulder dystocia?”

- “When a baby has experienced a shoulder dystocia, what can happen to the baby’s arm?”

Regularly perform multidisciplinary shoulder dystocia drills. The Joint Commission recommends that clinical drills be performed to help staff prepare for high-risk labor and delivery events, including shoulder dystocia, emergency cesarean delivery, and maternal hemorrhage.13

When shoulder dystocia occurs, extensively chart the event and interventions used. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has developed a patient safety checklist focused on key clinical elements in the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum periods and overall timing of the delivery to document when a shoulder dystocia occurs.14

Stop using the term “traction” in the medical record and obstetric literature. Words are meaningful and open to multiple interpretations. Often, words have unintended consequences. Plaintiff attorneys often highlight the obstetrician’s use of “traction” or “excessive traction” as the cause of an OBP injury. Orthopedic surgeons and pediatricians often state in their records that the OBP injury was a “traction injury,” further supporting the plaintiff attorney’s contention that excessive traction applied by the obstetrician caused the traction injury. Obstetricians do not use traction to deliver a baby. Motorized tractors generate traction, not obstetricians. We use gentle downward guidance to deliver the fetal shoulders and body.

In a high-risk situation, proceed quickly to delivery of the posterior arm. When you recognize a shoulder dystocia in a high-risk situation (maternal diabetes and large fetus), it may be wise to move quickly to delivery of the posterior arm.15,16 In high-risk situations, delivery of the posterior arm is the maneuver with the greatest likelihood of resolving a severe shoulder dystocia, with the least force applied to the brachial plexus that is trapped under the mother’s symphysis pubis.