Dao and colleagues concluded that the timing of pregnancy after gastric bypass is irrelevant.23 However, critical review of their data reveals an average weight gain of 4 lb in the group of women who became pregnant within a year after surgery (range, -70 to +45 lb), compared with 34 lb in the group that waited at least 1 year to conceive (range, +13 to +75 lb). As it was among our own patients, miscarriage was more common in the early group (24% vs 8% in the late group). Although these data are not statistically significant, they should arouse concern. I believe the most prudent advice to give women following bariatric surgery is to delay pregnancy until weight loss has stabilized.

The World Health Organization has estimated that there are 1 billion overweight adults on the planet. The problem of obesity, however, is concentrated in the United States. For well over a decade, the problem has escalated, with the US obesity rate referred to as “epidemic” and “a crisis”—among both adults and children.24

Among adults 20 years and older, the prevalence of obesity in the United States is 32%, and the prevalence of morbid obesity is almost 5%. Among adult women 20 to 39 years old, the prevalence of obesity and morbid obesity is 29% and 8%, respectively.27

Complications of bariatric surgery

Complications following bariatric surgery are intrinsic to the specific procedure performed. Because RYGB and the Lap-Band procedure constitute the overwhelming majority of bariatric operations, the most important complications associated with these surgeries will be addressed.

After RYGB, greatest risk is intestinal obstruction

Some of the early postoperative complications following RYGB are unlikely to be seen by physicians other than bariatric surgeons. They include anastomotic leaks, peritonitis, and bleeding. Pulmonary emboli should be managed as usual during the postoperative course. The amount of heparin necessary to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation may be quite substantial, but this fact should not deter the treating physician.

Nausea is almost universally present during the first few days after RYGB. When nausea and increasing food intolerance occur later (after the patient has demonstrated that food can be tolerated), it may indicate stenosis of the gastrojejunal anastomosis. The optimal study to evaluate these symptoms is a barium upper gastrointestinal (GI) swallow study. Stenosis can usually be managed by endoscopic dilatation.24

Intestinal obstruction. One of the most serious problems following RYGB is intestinal obstruction, which may be caused by internal hernia, adhesion, intussusception (not rare in the gastric bypass patient), and other less common causes ( FIGURE 1 ). Intestinal obstruction may occur early or years after the procedure.

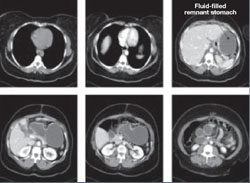

In the RYGB patient, obstruction manifests with prominent pain, but distension and vomiting are usually absent, and plain abdominal radiographs are generally normal. The reason for this unusual presentation? The biliopancreatic limb tends to be the segment involved in the blockage, thereby creating a closed-loop obstruction. The most efficient way to diagnose this potentially life-threatening problem is by computed tomography (CT) ( FIGURE 4 ).

FIGURE 4 CT facilitates diagnosis of closed-loop obstruction

These computed tomography images reveal obstruction of the remnant stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunum (the biliopancreatic limb) in a patient who has undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Lap-Band complications may be pervasive

The Lap-Band procedure is often touted as having very low morbidity and mortality. However, data from outside the United States, where longer follow-up has been conducted, have cast a shadow of doubt on the supposed benefits of this restrictive procedure.

One study involving nearly 900 patients and 12 years of follow-up identified a rate of late complication of nearly 28% (2.3%, band erosion; 15.5%, pouch dilatation; 8.9%, port problems) and a rate of major reoperation of nearly 30%. The failure rate increased over time, reaching 65% at 10 years.

Despite these concerns, there is widespread enthusiasm among patients and bariatric surgeons who are proponents of this procedure.

A life-threatening complication. Any physician who might care for a patient who has undergone a Lap-Band procedure should be aware of one potentially life-threatening consequence: a slipped band. This complication can lead to incarceration of the stomach—usually the fundus—which, if left untreated, causes gastric infarction.

The main symptom of band slippage is pain. Any patient who has a Lap-Band and who reports significant upper abdominal pain must be evaluated to exclude slippage. Evaluation usually consists of a swallow study. Surgical correction is mandatory and urgent.

Like complications of surgery, the nutritional demands following bariatric surgery depend on the type of procedure that is performed.