At her first prenatal visit at 14 weeks’ gestation, a 41-year-old woman (G2P1) presents with a dichorionic twin gestation, blood pressure (BP) of 105/68 mm Hg, and a body mass index (BMI) of 40 kg/m2. The pregnancy was achieved through in vitro fertilization. Ten years earlier, the patient’s first pregnancy was complicated by preeclampsia, requiring preterm delivery at 33 weeks’ gestation.

By 28 weeks’ gestation, the patient has gained 26 lb. Her BP is 120/70 mm Hg, with no proteinuria detected by urine dipstick. By 30 weeks, she has gained an additional 8 lb, her BP is 142/84 mm Hg, and no proteinuria is detected. At 32 weeks, her BP is 140/92 mm Hg, she has gained another 8 lb, and no proteinuria is present. She also reports new-onset headaches that do not respond to over-the-counter analgesics. She is sent to the obstetric triage area for BP monitoring, blood testing for preeclampsia and nonstress test fetal monitoring.

During the 2-hour observation period, the patient continues to report headaches, and swelling of her face and hands is present. Her systolic BP values range from 132 to 152 mm Hg, and diastolic values range from 80 to 96 mm Hg. No proteinuria is detected, blood testing results for preeclampsia (complete blood count, liver enzymes, serum creatinine, and uric acid) are normal, and the nonstress tests are reactive in both fetuses.

The patient is given a diagnosis of gestational hypertension, along with a prescription for oral labetalol 200 mg daily and two tablets of acetaminophen with codeine for the headaches (to be taken every 6 hours as needed). She is sent home with instructions to return to her physician’s office in 1 week.

Two days later, she wakes in the middle of the night with a severe headache, blurred vision, and vomiting. Her husband calls the obstetrician’s answering service and is instructed to call 911 immediately. While waiting for an ambulance, the patient experiences a grand mal eclamptic convulsion. A second convulsion occurs during her transfer to the ED.

This scenario could have been avoided.

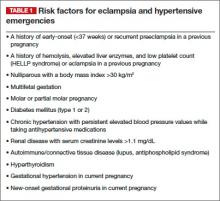

The obstetrician in this case was negligent for failing to recognize preeclampsia in a patient who had two clear risk factors for it: multifetal gestation and a history of early-onset (<37 weeks) preeclampsia in an earlier pregnancy (other risk factors are listed in TABLE 1).

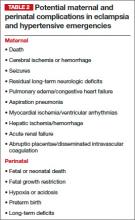

As a result, the patient developed eclampsia, a serious condition that can lead to grave maternal complications (TABLE 2), including death. It also can cause fetal complications, including growth restriction, hypoxia, acidosis, preterm birth, long-term developmental deficits, and death.1,2

The obstetrician in this case also overlooked published evidence indicating that, in the setting of hypertension and headaches, as many as 20% to 30% of pregnant women whose tests for proteinuria show a negative or trace result via dipstick will develop eclampsia.3 Instead of initiating outpatient administration of oral antihypertensive agents, the obstetrician should have hospitalized this patient for at least 48 hours, with steroid administration, to determine whether outpatient management was feasible.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia Baha Sibai, MD (November 2011)

Eclampsia is marked by the onset of convulsions (during pregnancy or postpartum) in association with gestational hypertension alone, proteinuria, preeclampsia, or superimposed preeclampsia. Although it is rare, eclampsia is potentially life-threatening. For that reason, obstetricians, anesthesiologists, ED physicians, neurologists, and critical-care physicians should be well versed in its diagnosis and management. In this article, I focus on management.

Eclampsia can develop any time during the antenatal period (>16 weeks’ gestation), during labor and delivery, and as long as 6 weeks after delivery. Therefore, we should be vigilant for preeclampsia whenever a pregnant patient visits our office, as well as when she makes unscheduled visits to the ED or obstetric triage area or is hospitalized.

Early recognition of women at high risk for preeclampsia and eclampsia may allow for prompt intervention, including early hospitalization for close observation prior to delivery and postpartum.1,2,4–10

Hospitalization of high-risk women allows for use of antihypertensive agents to treat severe BP, administration of magnesium sulfate to prevent convulsions, and timely delivery of the infant. It also allows for intensive maternal support during and after an eclamptic seizure.

Hospitalization is essential for women who exhibit features that suggest severe disease. More specifically, the presence of gestational hypertension with any of the following features is an indication for immediate hospitalization for evaluation and management:

- persistent severe hypertension (systolic

BP ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥110 mm Hg) for at least 1 hour - gestational hypertension requiring oral antihypertensive therapy

- progressive and excessive weight gain (≥20 lb prior to 28 weeks’ gestation)

- generalized swelling (edema of hands or face)

- new-onset or persistent headaches despite analgesics

- persistent visual changes (blurred vision, scotomata, photophobia, double vision)

- shortness of breath, dyspnea, orthopnea, or tightness in the chest

- persistent retrosternal chest pain, severe epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

- persistent nausea, vomiting, malaise

- altered mental state, confusion, numbness, tingling, or motor weakness

- platelet count below 100 3 103 µL

- aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), or lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) levels more than twice the upper limit of normal

- serum creatinine level >1.1 mg/dL

- suspected abruptio placentae.