Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer

• whether a photograph was enclosed

• whether additional items were enclosed (eg, gifts, drawings)

• whether the letter was rejected by prison authorities

• the writer’s purpose.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Letters were assigned to 1 of 5 categories:

Acquaintance letters sought ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer. They focused largely on conveying information about the writer.

Show of support letters also sought an ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer, but instead focused on him, not the writer.

Romance letters used words that conveyed romantic or non-platonic affection.

Spiritual letters gave advice to the murderer with a religious tone.

Words of wisdom letters offered advice but lacked a religious tone.

Given the nonstandardized nature of categorization and the lack of a formal questionnaire, we were unable to perform an exploratory factor analysis on our categorizations. Inter-rater reliability of letter categorization was 0.79.

Results: Writer profiles, purpose for writing

In all, we reviewed 819 letters:

• Thirty-five letters were excluded because they were written by family members, children, or other prisoners

• Of the remaining 784 letters, there were 333 unique writers

• Two-hundred sixty letters were written by women, 61 by men; 2 were co-written by both sexes; sex could not be determined for 10.

Women were more likely than men to write a letter (P = .014) and to write ≥3 letters (P = .001). The age of the writer was determined for 117 (35.1%) letters; mean age was 27.8 (± 8.9) years (range, 18 to 59 years).

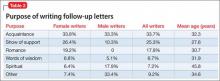

The purpose of the letters differed by sex (P < .001) but not by the writer’s age (P = .058). Women were more likely than men to write letters categorized as “Acquaintance,” “Romance,” and “Show of support”; in contrast, men were more likely than women to write a letter categorized as “Spiritual” (Table 1). Approximately 95% of letters were handwritten. Letters averaged 3 pages (range, 1 to 16 pages).

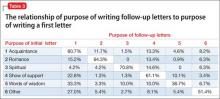

Two-hundred sixteen writers wrote a single letter; 53 wrote 2 letters; 18 wrote 3 letters; 11 wrote 4 letters; 30 wrote 5 to 10 letters; and 9 wrote 11 to 43 letters. The purpose of follow-up letters was associated with the age of the writer (P < .001) and with the writer’s sex (P < .001). Women were more likely to write “Show of support” and “Romance” follow-up letters; men were more likely to write “Spiritual” follow-up letters (Table 2).

Results suggested that the purpose of the initial letter was a reasonable predictor of the purpose of follow-up letters (P < .001) (Table 3). The murderer never responded to any letters. Letters were most often written from his state of incarceration; next, from contiguous states; then, from non-contiguous states; and, last, from international locations (P < .001).