Underlying the nation’s opioid abuse epidemic is the fact that physicians are undertrained, underresourced, and using incorrect assessment tools to diagnose and treat chronic pain, according to an expert panel.

“I don’t know how a primary care doctor can manage a chronic pain patient,” said Dr. William S. Jacobs, chief of addiction medicine at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta. “They’re given 15 minutes to treat multiple medical problems, from diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, to asthma, and oh, by the way, the patient has chronic pain. I couldn’t handle one of those problems in 15 minutes. How can they manage to do it?” asked Dr. Jacobs, who also serves as medical director of the Bluff Plantation addiction recovery center, also in Augusta.

He spoke during a Nov. 17 webcast called “Opiate Misuse, Overdose & Addiction – Causes & Solutions” as part of the Fall Lecture Series at the Drug Enforcement Agency Museum in Arlington, Va.

About 2.5 million Americans are addicted to prescription pain medications and increasingly to heroin, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Nearly two-thirds of those people were introduced to opiates in their physician’s office, according to panelist Theodore Cicero, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and vice chairman for research at Washington University in St. Louis.

According to NIDA, in 1991, 76 million opioid prescriptions were written, compared with the 207 million written in 2013.

Although that figure is down from the 219 million opioid prescriptions written in 2011, Dr. Cicero presented new data indicating this is not as promising as it might seem, because the less legal opiates are prescribed, the more people addicted to them are crossing over to heroin. “It’s cheaper, easy to get, easy to inject, and provides an intense high,” Dr. Cicero said.

Whereas stigma might have prevented users in the past from crossing over to heroin, once addicted, users care less about their reputation and more about avoiding withdrawal, Dr. Cicero said.

Compounding the situation, said Dr. Jacobs, is the insidious nature of a legal drug being prescribed by a trusted source, who too often has not been specifically educated in pain management, and who does not pay enough attention to patient education and informed consent. Dr. Jacobs said chronic pain patients already treated with opiates such as oxycontin and hydrocodone before their referral to a pain specialist often “have no idea how dangerous the medications that they were being prescribed were.”

Both presenters said not enough data exist currently to predict who is most likely to become addicted to prescription medication, but Dr. Cicero said his research (N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1789-90), based on a survey of 267 prescription painkiller medicine users who crossed over to heroin, indicate they tend to have in common “extremely low self-esteem and lots of problems with anxiety and depression, and they find that, at least temporarily, the opiates relieve these.”

This might be in part tied to what Dr. Jacobs said is the brain’s inability to distinguish physical pain from emotional pain. “It’s no wonder that when we give a patient chronic opiates, and they develop emotional stress in their lives, that they turn to the opiates to try and fix that.”

That pain is subjective, and not as easily quantified as hypertension, for example, which also makes it difficult for physicians to know the appropriate timing of intervening with opiates when a patient reports pain. Plus, said Dr. Jacobs, since the 1990s when pain became “the fifth vital sign,” the parameters of chronic pain gradually have shrunk from a condition that lasted a year, to 6 months, to 3 months, until now, patients undergoing any given surgery are sent home with a prescription for pain medication to last for 2 weeks, whether or not it is indicated.

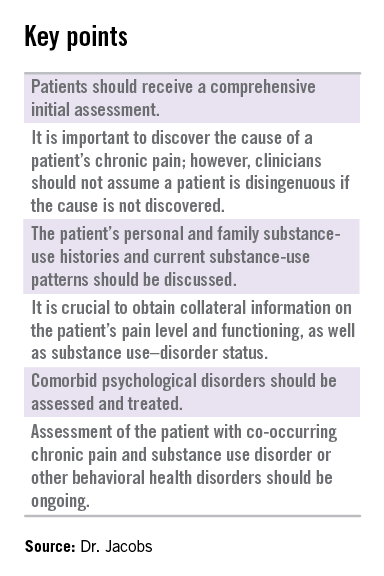

When prescribers do suspect that a pain medication might be indicated, Dr. Jacobs said, analog scales for assessing pain are “worthless,” because they don’t help to identify the cause of a patient’s pain, nor do they indicate any psychiatric comorbidities. Instead, Dr. Jacobs specifically recommended the validated Mankoski Pain Scale, which he said provides a comprehensive and specific initial assessment, not only of pain, but the context in which it occurs.

Dr. Jacobs and Dr. Cicero had no disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight