Since 2008, the FDA has cleared 4 transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) devices for treating depression (Related Resources). In that time, the availability of TMS has steadily grown within and outside the United States.

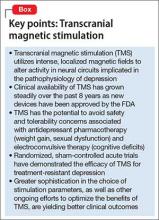

Parallel with increasing clinical utilization of this technology, research continues into the benefit of TMS for treatment-resistant depression; such research includes additional, supportive, acute, sham-controlled trials; comparison trials with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for more severe episodes of depression; short- and long-term real-world outcome studies; exploration of alternative treatment parameters to further enhance its efficacy; and the development of other TMS approaches. In this article, we review recent developments in the application of TMS to treat major depressive disorder—in particular, treatment-resistant depression (Box).

Therapeutic neuromodulation

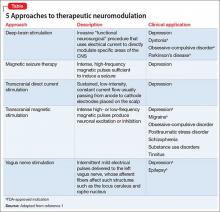

The underlying premise of neuromodulation is that the brain is an electrochemical organ that can be modulated by pharmacotherapy or device-based approaches, or their combination.1 ECT is the prototypic device-based neuromodulation approach, and remains one of the most effective treatments for severe depression.

More recently, however, other methods have been, and continue to be, developed to treat patients who do not achieve adequate benefit from psychotherapy or medical therapy, or both, and who might not be an ideal candidate for ECT (Table,1). In addition to the potential therapeutic benefit of these alternative strategies, some could avoid safety and tolerability concerns associated with medication (weight gain, sexual dysfunction) and ECT (eg, cognitive deficits).

TMS, which utilizes intense, localized magnetic fields to alter activity in neural circuits implicated in the pathophysiology of depression, represents an important example of this initiative.2

TMS has established efficacy for depression

Sham-controlled trials. Several randomized, sham-controlled acute trials have demonstrated the efficacy of TMS for treatment-resistant depression.

A recent meta-analysis considered 18 studies (N = 1,970) that met the authors’ criteria for inclusion.3 They found that TMS monotherapy was statistically and clinically more effective than a sham procedure based on:

- improvement in depressive symptoms (mean decrease in baseline Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS] score, −4.53 [95% CI, −6.11 to −2.96])

- response rate; response was 3 times more likely with TMS (relative risk 3.38 [95% CI, 2.24 to 5.10])

- remission rate; remission was 5 times more likely with TMS (relative risk, 5.07 [95% CI, 2.50 to 10.30]).

Another meta-analysis (7 studies, N = 279) considered TMS as an augmentation strategy to standard medication for treatment-resistant depression.4 The authors reported that, based on change in HDRS scores, the pooled standardized mean difference between active and sham TMS augmentation was 0.86 (P < .00001). Furthermore, the pooled response rate with TMS augmentation was 46.6%, compared with 22.1% with the sham procedure (P < .0003).

Acute naturalistic TMS studies. The efficacy of TMS is supported by a large, naturalistic study of 307 patients with treatment-resistant depression who were assessed at baseline and during a standard course of TMS.5 Considering change score in the Clinician Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) scale, significant improvement was seen from baseline to end of treatment (−1.9 ± 1.4; P < .0001), with a clinician-assessed response rate of 58.0% and remission rate of 37.1%. Of note: Self-reported quality-of-life measures (on the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey and EuroQol 5-Dimensions) also significantly improved during this relatively brief period.6

Maintenance strategies after acute TMS response. Most patients referred for TMS have a depressive illness characterized by a chronic, relapsing course and inadequate response to pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, or their combination. An effective maintenance strategy after acute response to TMS is paramount. This includes:

- prolonged tapering schedule after an acute TMS course is completed

- maintenance medication or psychotherapy, or both

- scheduled periodic maintenance TMS sessions (usually as an augmentation strategy)

- reintroduction of TMS as needed with early signs of relapse. In this context, several trials have assessed the durability of acute TMS benefit.

A semi-controlled maintenance study followed 99 patients who had at least a 25% decrease in baseline HDRS score after acute TMS treatment.7 They were then tapered from their TMS sessions over 3 weeks while an antidepressant was titrated up. If, at any time during the subsequent 6 months, early signs of depression relapse were noted (ie, change of at least 1 point on the CGI-S for 2 consecutive weeks), TMS was reintroduced. At the end of the trial, 10 patients (13%) had relapsed and 38 (38%) had an exacerbation of symptoms sufficient to warrant reintroduction of TMS. Of those, 32 (84%) re-achieved mood stability.

In another study, 50 patients who had achieved remission during an acute course of TMS were followed for 3 months.8 After TMS taper and continued pharmacotherapy or naturalistic follow-up, 29 (58%) remained in remission; 2 (4%) maintained partial response; and 1 (2%) relapsed.