Communities across the United States have experienced a near-epidemic of opioid abuse. Deaths from opioid overdose have doubled since 2000 and increased 14% from 2013 to 2014.1 Treatment strategies for opioid use disorder (OUD) target individual well-being with the goal of preventing relapse. Most treatment approaches help patients gain self-confidence and have been described by patients as “giving them their life back.”

Broadly, the major phases of treatment for OUD are similar to those for other substance use disorders, and involve acute detoxification followed by long-term maintenance of sobriety. There are 3 main phases of treatment for OUD:

- treatment engagement

- stabilization and harm reduction

- sustained abstinence.

Long-term maintenance of sobriety in OUD could involve medications that are FDA-approved for this indication: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Psychosocial interventions can be used individually and in combination with pharmacotherapy. Because OUD is a chronic disorder typically characterized by intermittent relapse, patients could move back and forth between the different phases of treatment.

In this article, we highlight the medication and non-medication treatment options for the long-term management of OUD.

Defining abuseExogenous opioids are synthetic substances used for their analgesic and morphine-like properties. Opioids are indicated for the treatment of certain pain conditions and exist in varying potencies and delivery systems, which are tailored for specific types of pain.2 Opioids work through activity at opioid receptors found in the brain, spinal cord, gut, and other organs. Agonism of specific opioid receptors results in a decreased perception of pain and contributes to their abuse potential.

Because of their abuse potential, prescription of opioids is governed by the Controlled Substances Act3 of the United States. Despite these regulations, approximately 4.5% of U.S. adults from a nationally representative sample were found to be misusing prescription opioids.4 Another study used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and showed an increasing prevalence of OUD involving prescription drugs and resulting in increased mortality.5 The mortality rate from prescription opioids was found to be higher than for all other illicit drugs combined in 2013.6 Recently, Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which is intended to address the opioid crisis by expanding access to treatments for opioid overdose and addiction treatment services.7

The term “opioid use disorder” is found in DSM-58 and replaces the previous diagnoses of opioid abuse and dependence in DSM-IV-TR.9 OUD is characterized by a strong desire to continue using opioids despite problems associated with their use. Patients with OUD often experience cravings for opioids, tolerance, repeated failures at cutting down or limiting use, and decreased involvement in social activities.

Maladaptive use of opioids can result in physiologic dependence and lead to withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, drug craving, insomnia, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, diarrhea, and piloerection. However, physiologic dependence might not necessarily lead to development of OUD, which can be diagnosed when enough other diagnostic criteria present in the absence of physiologic dependence.

Misuse of prescription opioids is more prevalent among patients who meet criteria for other substance use disorders than among patients who do not.10 Misuse of prescription opioids often results in greater health care utilization, including the need for emergency services, hospitalization, and detoxification.

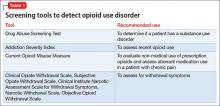

Assessing for OUDThe Addiction Severity Index was designed to classify and monitor misuse of opioids. The Index has poor sensitivity; it detects recent opioid use but fails to differentiate patients using prescribed opioids from those who are abusing opioids.11 By comparison, the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) was developed to monitor opioid use in chemical dependency treatment settings.12 The COMM has reliable internal consistency13 and validity and can be used to assess use of opioids outside of routine medical care. To gauge the severity of withdrawal symptoms, the Objective Opioid Withdrawal Scale or Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale14 can be used. Table 1 summarizes some standardized tools used to assess OUD.

Neurobiological considerationsOpioids work through activity at mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors. These receptors are present in both the peripheral and the central nervous system. Exogenous opioids work through activity at G protein-coupled receptors and by activating specific neurotransmitter systems. The effect of a given opioid drug is dependent on the type and location of receptors it modulates and can range from CNS depression to euphoria.

For example, mu receptor activation produces sedation, euphoria, or analgesia depending upon the location, frequency, and duration of receptor occupancy. Activation of CNS mu receptors can cause miosis and respiratory depression, whereas mu receptor activation in the peripheral nervous system can cause constipation and cough suppression. Mu receptor stimulation through various G-proteins triggers the second messenger cascade, generating enzymes such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate.