It is important to understand the natural course of syphilis, its implication on psychiatric symptom production, and long-term psychiatric prognosis.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by T pallidum, a spirochete, that has varied clinical presentations. Osler called syphilis the “great imitator” for its array of system involvement, ranging from asymptomatic infection and afferent pupillary defect to depression, psychosis, and dementia. With wide use of penicillin, the rate of neurosyphilis declined steadily during the mid 1990s. By 1997, the overall rate reached its lowest point in the United States; in 1999 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a national plan to eliminate syphilis.1 By 2004, however, prevalence had increased to 4.7/100,000. It is thought that this increase is mainly associated with substance use (especially crack cocaine) and HIV co-infection. Most cases were distributed in economically depressed geographical areas.

Psychiatric patients are at higher risk of acquiring the infection because of substance use, lack of education on safer sex practices, and impulsive behavior.

Stages of syphilis

Syphilis does not follow a step-wise progression. One-third of cases progress to the tertiary stage, even many years after initial infection, without adequate treatment.2

Almost 10% syphilis cases present with neurologic symptoms,3 and neurologic involvement can occur at any stage of disease progression. The most common symptoms of syphilis are presented in Table 1.

A range of psychiatric symptoms have been reported among patients with syphilis, including anhedonia, suicidality, mania, grandiosity, persecutory delusions, auditory and visual hallucinations, paranoia, and cognitive impairment. The incidence of psychiatric symptoms is not clearly described in literature.

Diagnosis and treatment

Neurosyphilis, at any disease stage, should be suspected if a patient:

- exhibits suggestive symptoms

- does not respond to antibiotic treatment

- has late latent syphilis

- is immunocompromised.

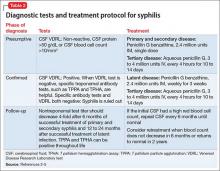

Lumbar puncture and examination of CSF is the most useful diagnostic test. Dark field microscopy to reveal T pallidum is definitive, but only is applicable during the primary stage. The role of dark field microscopy of the CSF sample to diagnose neurologic involvement has not been established. Tests and treatment protocol are described in Table 2.2-5

Treatment of psychiatric symptoms of neurosyphilis

There are inconsistent and limited data about the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in neurosyphilis. A retrospective study6 of 161 patients with neurosyphilis in South Africa reported that 50.9% exhibited a complex spectrum of symptoms that included delirium and dementia. Of treated patients, 17% continued to have residual symptoms during follow-up.

A review of the literature did not reveal any widely accepted guideline for screening for neurosyphilis in general psychiatry practice or a treatment protocol for psychiatric symptoms. This lack of guidance could be attributed to the rarity of the disease, cost-benefit analyses, and low specificity of antibody tests. In the literature, syphilis screening is recommended as a routine protocol when evaluating and treating dementia.7

In most studies, a diagnosis of neurosyphilis was confirmed by CSF examination; however, many of these studies did not report a specific follow-up CSF examination protocol. Most of these patients were treated with an antipsychotic with partial improvement in symptoms, even after standard antibiotic protocol.8

First- and second-generation antipsychotics and mood stabilizers have been shown to be useful in the acute treatment of psychosis and agitation.8 In few instances, the psychotropic medication was continued beyond several months and the patient was placed in a long-term care facility. Psychiatric symptoms persisted for many years with or without residual neurosyphilis symptoms, possibly because of permanent neuronal loss.

Clinical considerations

It often is difficult to distinguish a preexisting psychiatric disorder made worse by neurosyphilis from a secondary psychiatric disorder caused by neurosyphilis. The 2 might coexist, or psychiatric symptoms could be wrongly attributed to schizophrenia because of a lack of careful clinical evaluation.

Often, the follow-up diagnostic protocol for neurosyphilis is not followed; as a result, the need for re-treatment remains unclear. Rarity of the disease makes it difficult to perform a prospective, randomized study to determine the duration and effect of long-term psychiatric treatment.

Close follow-up and consideration of the risk vs benefit of psychotropic medication is key. Because there are no proven guidelines for the length of treatment with antipsychotics, it is prudent to minimize their use until psychiatrically indicated. Side effects, such as (in Mr. C’s case) changes in the QTc interval, should warrant consideration of discontinuing psychotropic medication. Interdisciplinary collaboration with neurology and infectious disease will improve the overall outcome of a complex clinical presentation.