Renal disease can play a large role in altering the pharmacokinetics of medications, especially in elimination or clearance and plasma protein binding. Specifically, renal impairment decreases the plasma protein binding secondary to decreased albumin and retention of urea, which competes with medications to bind to the protein.1

Electrolyte shifts—which could lead to a fatal arrhythmia—are common among patients with renal impairment. The risk can be further increased in this population if a patient is taking a medication that can induce arrhythmia. If a drug is primarily excreted by the kidneys, elimination could be significantly altered, especially if the medication has active metabolites.1

Normal renal function is defined as an estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) of >80 mL/min. Renal impairment is classified as:

- mild: eCrCl, 51 to 80 mL/min

- moderate: eCrCl, 31 to 50 mL/min

- severe: eCrCl, ≤30 mL/min

- end-stage renal disease (ESRD): eCrCl, <10 mL/min.2

Overall, there is minimal information about the effects of renal disease on psychotropic therapy; our goal here is to summarize available data. We have created quick reference tables highlighting psychotropics that have renal dosing recommendations based on manufacturers’ package inserts.

Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Dosage adjustments based on renal function are not required for any FGA, according to manufacturers’ package inserts. Some of these antipsychotics are excreted in urine, but typically as inactive metabolites.

Although there are no dosage recommendations based on renal function provided by the labeling, there has been concern about the use of some FGAs in patients with renal impairment. Specifically, concerns center around the piperidine phenothiazines (thioridazine and mesoridazine) because of the increased risk of electrocardiographic changes and medication-induced arrhythmias in renal disease due to electrolyte imbalances.3,4 Additionally, there is case evidence5 that phenothiazine antipsychotics could increase a patient’s risk for hypotension in chronic renal failure. Haloperidol is considered safe in renal disease because <1% of the medication is excreted unchanged through urine.6

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Overall, SGAs are considered safe in patients with renal disease. Most SGAs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism before excretion, allowing them to be used safely in patients with renal disease.

Sheehan et al7 analyzed the metabolism and excretion of SGAs, evaluating 8 antipsychotics divided into 4 groups: (1) excretion primarily as an unchanged drug in urine, (2) changed drug in urine, (3) changed drug in feces, (4) and unchanged drug in feces.

- Paliperidone was found to be primarily excreted as an unchanged drug in urine.

- Clozapine, iloperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone all were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in urine.

- Aripiprazole and ziprasidone were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in feces.

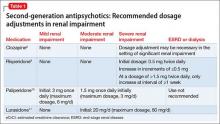

The manufacturers’ package inserts for clozapine, paliperidone, risperidone, and lurasidone have recommended dosage adjustments based on renal function (Table 1).8-11

Ziprasidone. Although ziprasidone does not have a recommended renal dosage adjustment, caution is recommended because of the risk of electrocardiographic changes and potential for medication-induced arrhythmias in patients with electrolyte disturbances secondary to renal disease. A single-dosage study of ziprasidone by Aweeka et al12 demonstrated that the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone are unchanged in patients with renal impairment.

Asenapine. A small study by Peeters et al13 evaluated the pharmacokinetics of asenapine in hepatic and renal impairment and found no clinically relevant changes in asenapine’s pharmacokinetics among patients with any level of renal impairment compared with patients with normal renal function.

Aripiprazole. Mallikaarjun et al14 completed a small study evaluating the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in patients with renal impairment. They found that the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in these patients is no different than it is in patients with normal renal function who are taking aripiprazole.

Quetiapine. Thyrum et al15 conducted a similar study with quetiapine, which showed no significant difference detected in the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in patients with renal impairment. Additionally, quetiapine had no negative effect on patients’ creatinine clearance.

Lurasidone. During clinical trials of lurasidone in patients with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, the mean Cmax and area under the curve was higher compared with healthy patients, which led to recommended dosage adjustments in patients with renal impairment.11

As mentioned above, renal impairment decreases the protein binding percentage of medications. Hypothetically, the greater the protein binding, the lower the recommended dosage in patients with renal impairment because the free or unbound form correlates with efficacy and toxicity. Most FGAs and SGAs have the protein-binding characteristic of ≥90%.16 Although it seems this characteristic should result in recommendations to adjust dosage based on renal function, the various pharmacokinetic studies of antipsychotics have not shown this factor to play a role in the manufacturers’ recommendations.