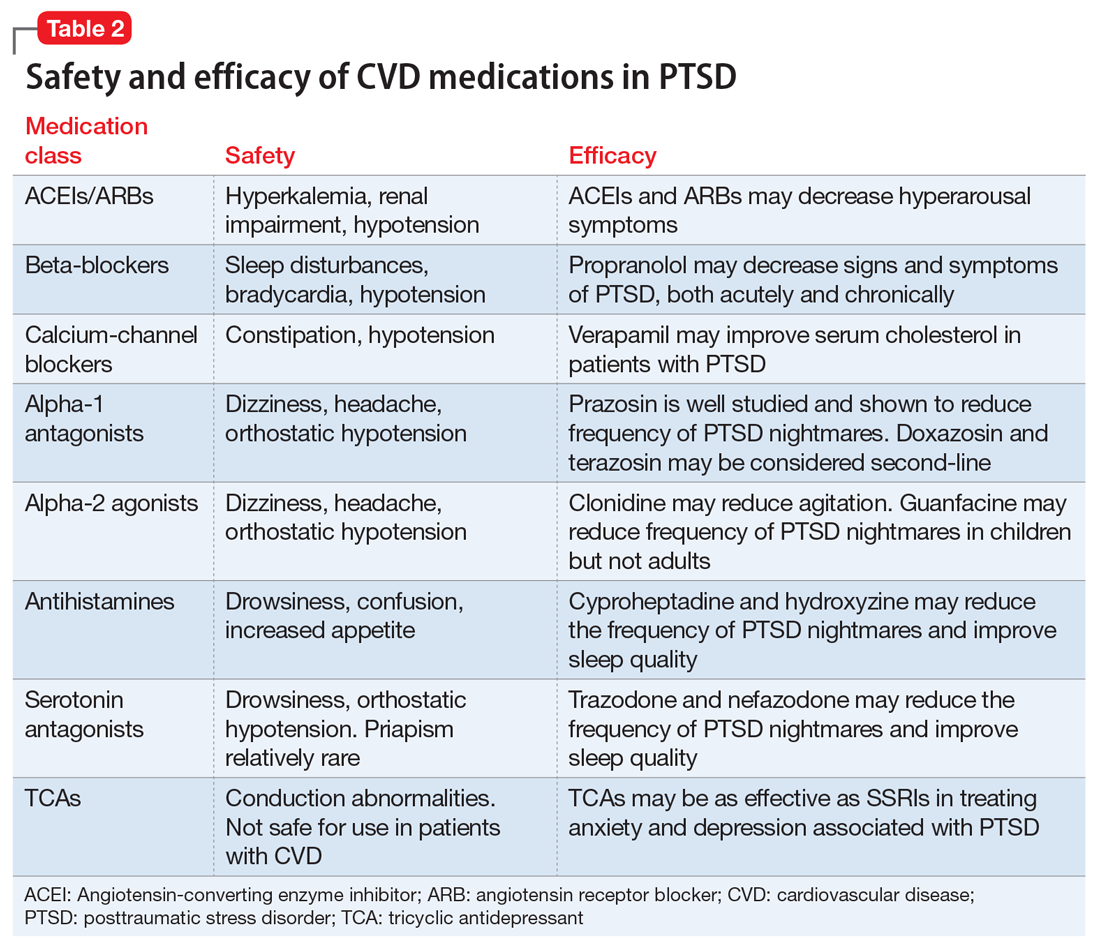

ACEIs, ARBs, beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) inhibit the renin-angiotensin system: ACEIs prevent formation of angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor, and ARBs prevent interaction between angiotensin II and its receptor. In one study, patients were recruited from a large public hospital serving primarily a highly traumatized, low-income population. Patients taking an ACEI or ARB who had experienced at least 1 traumatic event exhibited significantly decreased hyperarousal symptoms and decreased intrusive thoughts on the PTSD Symptom Scale and Clinician Administered PTSD Scale.5 Other studies have reported that blockade of angiotensin II AT1 receptors may result in decreased stress, anxiety, and inflammation.15

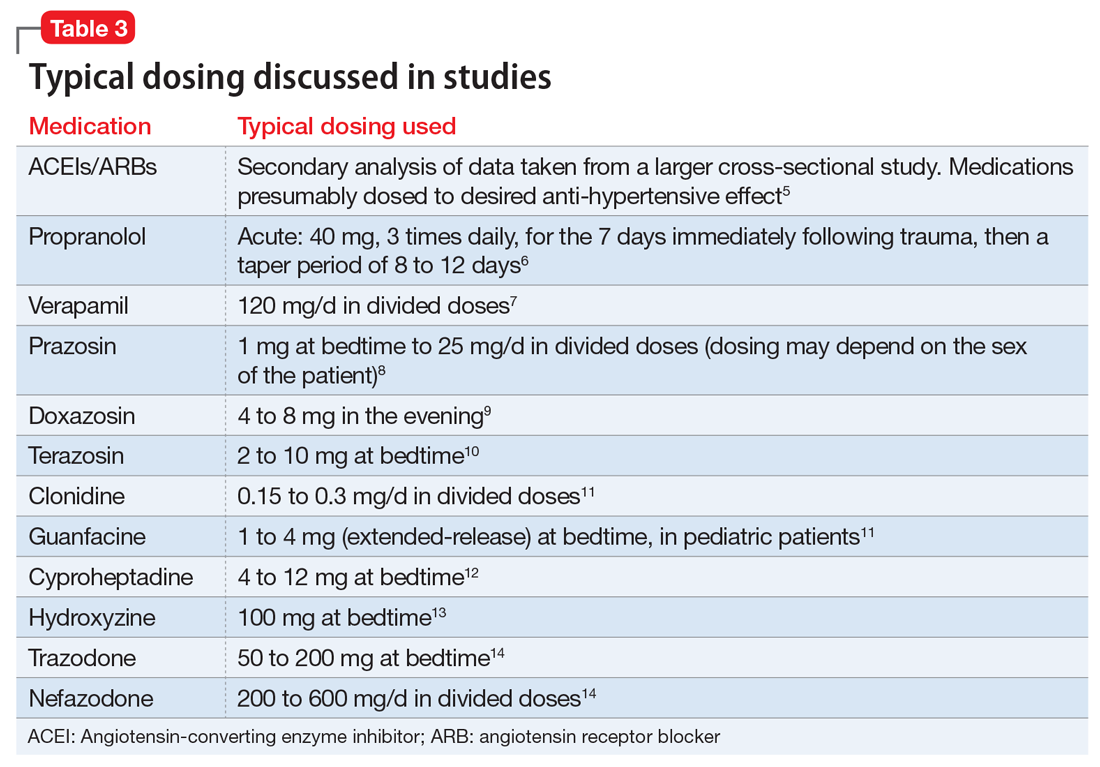

Evidence supports the use of the centrally acting, beta-adrenergic antagonist propranolol for decreasing the physiologic reactivity to acute trauma. Emotional arousal enhances the consolidation of emotional experiences into long-term memories via the adrenal stress hormones epinephrine and corticosterone. The amygdala mediates these stress hormones and releases norepinephrine, which subsequently activates noradrenergic receptors essential for memory enhancement. Several studies have reported that patients who received propranolol within several hours of a traumatic event experienced fewer physiologic signs of PTSD at follow-up 1 month later.16 Moreover, researchers have hypothesized that chronic treatment with propranolol may be effective in decreasing hyperarousal symptoms in patients with chronic PTSD by reducing tonically elevated norepinephrine signaling.6

Chronic elevation of noradrenergic activity may induce lipoprotein lipase and suppress low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor activity, which in turn elevates serum cholesterol levels. The results of one study suggested that verapamil, a non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, significantly improves serum cholesterol levels in patients with PTSD by increasing LDL receptor activity and decreasing norepinephrine release.7

Alpha-1 and alpha-2 antagonists

Alpha-1 antagonists relax vascular smooth muscle by blocking norepinephrine stimulation at postsynaptic α-1-adrenergic receptors. They frequently are prescribed for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy. One α-1 antagonist in particular, prazosin, appears especially useful in treating sleep disturbances, which occur in up to 90% of patients with PTSD.17 Because of its relatively greater lipophilicity, prazosin crosses the blood–brain barrier and acts centrally to reduce the fight-or-flight and hyperarousal reactions related to nightmares caused by PTSD.18 Common adverse effects include dizziness and orthostatic hypotension. These usually can be mitigated with titration to effective dose. In a study of active-duty soldiers who returned from Iraq and Afghanistan, Raskind et al8 found that prazosin doses up to 25 mg/d in men and 12 mg/d in women were tolerated with weekly adjustments and blood pressure monitoring.

Other α-1 antagonists have shown efficacy in a limited number of trials and may be considered second-line treatment of PTSD hyperarousal symptoms. Doxazosin has a longer half-life compared with prazosin (22 hours vs 3 hours) and may be useful in treating daytime hyperarousal with once-daily dosing. However, its hydrophilicity prevents it from crossing the blood–brain barrier to the same degree as prazosin.19 Terazosin also has a longer half-life (12 hours) and reaches peak plasma concentration in 1 hour. It undergoes minimal first-pass metabolism, leaving almost the entire circulating dose in the parent form, but clinical data are limited to only a small case report.10

Alpha-2 agonists inhibit sympathetic outflow in the CNS, which ultimately relaxes vascular smooth muscle like α-1 antagonists. Clonidine exhibits sedative properties, which derive from its nonspecific binding to α-2a-, -2b-, and -2c-adrenergic receptors. Several case studies have described a reduction in agitation in PTSD patients with the use of clonidine, likely through the induction of sleep and relaxation. Guanfacine, on the other hand, selectively binds to the α-2a-adrenergic receptor and therefore lacks the sedative properties of clonidine. Several placebo-controlled trials showed no alleviation of PTSD symptoms in adults with the use of guanfacine.11 However, case reports and open-label trials have suggested that guanfacine may reduce trauma-induced nightmares in pediatric patients. Further investigation is needed to clarify the potential use of guanfacine in pediatric PTSD.19

Antihistamines and antidepressants

Several second-line pharmacologic agents may be useful in patients with PTSD who are already taking cardiovascular medication. A limited number of studies have demonstrated reduced frequency of PTSD nightmares with the histamine-1 antagonists cyproheptadine and hydroxyzine, both of which exhibit minor anti-serotonergic properties.12,13 Likewise, the serotonin antagonists nefazodone and trazodone have been shown to reduce the frequency of PTSD nightmares, as well as improve overall sleep quality.14 Nefazodone should be considered an option only after treatment failure of multiple other medications, because it is associated with a small, but significant, risk of life-threatening hepatotoxicity.20

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may reduce anxiety and depression associated with PTSD to the same degree as SSRIs.21 However, their effect on PTSD-associated sleep disturbances is much less pronounced than other available medications.14 TCAs should be avoided in patients with CVD because they may exacerbate cardiac conduction abnormalities. This is especially true for those recovering from acute MI.22

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. S is started on prazosin, 1 mg at bedtime, titrated weekly to 6 mg at bedtime with regular blood pressure monitoring because of the risk of orthostatic hypotension. Although the frequency of his nightmares decreases to 1 or 2 per month, he still experiences flashbacks at the same frequency and intensity as before. Prazosin, 1 mg every morning, is added, titrated weekly to 4 mg every morning. This combination of morning and bedtime dosing leads to resolution of both nightmares and flashbacks along with a significant reduction in hyperarousal. Lisinopril is increased from 5 to 10 mg/d to address Mr. S’s uncontrolled hypertension; this change also could have contributed to the reduction in hyperarousal. CPT and fluoxetine are continued.