Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

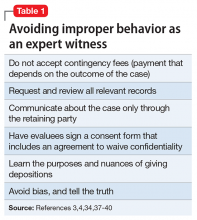

Table 13,4,34,37-40 lists ways forensic psychiatrists can avoid actions that constitute improper expert witness work.How to protect yourself

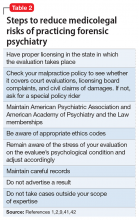

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

Table 21,2,9,41,42 lists steps to take to reduce medicolegal risk in forensic psychiatric work. As a final thought, a wise fellowship training program director once passed on some sage advice from Mark Twain: “When in doubt, tell the truth.”43 It’s a useful maxim not just for forensic practice, but for life in general.