Progesterone and ALLO. Chronic exposure to progesterone and ALLO (a main progesterone metabolite) and rapid withdrawal from ovarian hormones may play a role in the etiology of PMDD. Much like alcohol or benzodiazepines, ALLO is a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and has sedative, anesthetic, and anxiolytic properties. In times of acute stress, increased ALLO is known to provide relief.12,13 However, in women with PMDD, this typical ALLO increase might not occur.14

Patients with PMDD have been reported to have decreased levels of ALLO in the luteal phase.15-17 In one study, women with highly symptomatic PMDD had lower levels of ALLO compared with women with less symptomatic PMDD.14 A gonadotropin-releasing hormone challenge study showed the increase in ALLO response was less in PMDD patients compared with controls.17 Luteal-phase ALLO concentrations are reported to be lower in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a milder form of PMDD.14,17

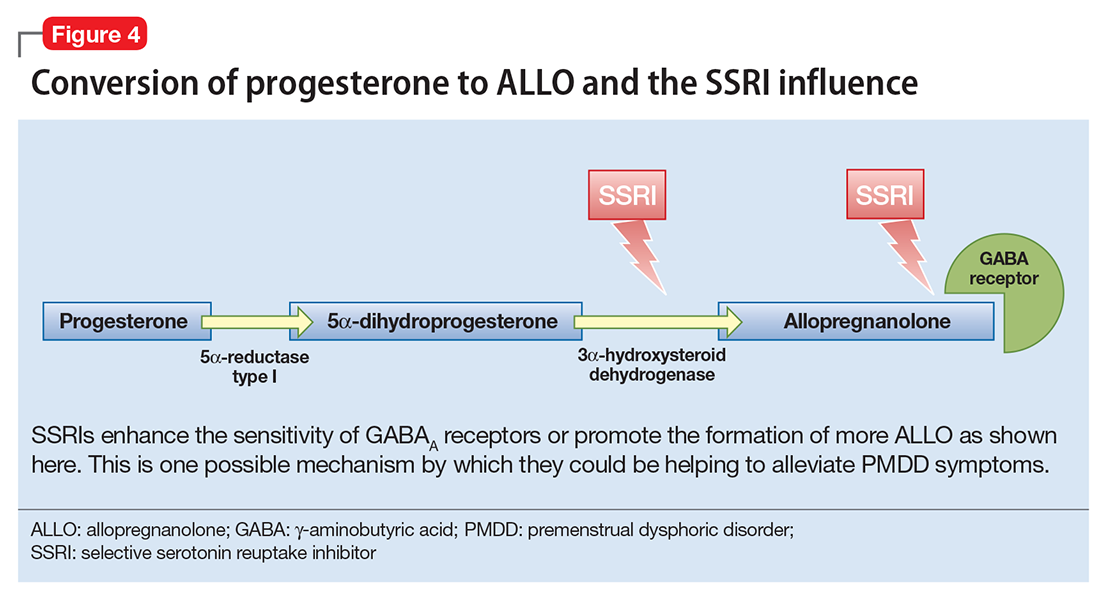

The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treating PMDD could be the result of the interaction of these medications with neuroactive steroids,18 possibly because SSRIs enhance the sensitivity of GABAA receptors or promote the formation of more ALLO (Figure 4).19-21

Estrogen, serotonin, and BDNF. Estrogen affects multiple neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood, cognition, sleep, and eating.22 Studying estrogen in context of PMDD is important because women with PMDD can have low mood, specific food cravings, and impaired cognitive function.

Estrogen–serotonin interactions are thought to be involved in hormone-related mood disorders such as perimenopausal depression and PMDD.23,24 However, the nature of their relationship is not yet fully understood. Ovariectomized animals have shown estrogen-induced changes related to serotonin metabolism, binding, and transmission in the regions of the brain involved in regulation of affect and cognition. Research in menopausal women also has provided some support for this interaction.24

Positron emission tomography studies in humans have found increased cortical serotonin binding modulated by levels of estrogen, similar to those previously seen in rat studies.24-27 One study showed an increased binding potential of serotonin in the cerebral cortex with estrogen treatment. This study further showed an even greater binding potential with estrogen plus progesterone, signaling a synergistic effect of the 2 hormones.28

SSRIs are an effective treatment for the irritability, anxiety, and mood swings of PMDD.29-30 Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, the serotonergic properties are certainly of primary attention. For some PMDD patients, SSRIs work within hours to days, as opposed to days or weeks for patients with depression or anxiety, which suggests a separate or co-occurring mechanism of action is in place. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, researchers administered the serotonin receptor antagonist metergoline to women with PMDD whose symptoms had remitted during treatment with fluoxetine and a group of healthy controls who were not receiving any medication.31 The women with PMDD experienced a return of symptoms 24 hours after treatment with metergoline but not with placebo; the controls experienced no mood changes.31

BDNF is a neurotransmitter linked to estrogen and likely related to PMDD. BDNF is critical for neurogenesis and is expressed in brain regions involved in learning and memory and also affects regulation.32 BDNF levels are increased by serotonergic antidepressants, affected by estradiol, and have cyclicity throughout the menstrual cycle.33-35

Putative brain structural and functional differences. Imaging studies have suggested differences in brain structure in women with PMDD, with a focus on the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. Women with PMDD have greater gray matter volume in the posterior cerebellum,36 greater gray matter density of hippocampal cortex, and lower gray matter density in the parahippocampal cortex.37

Some studies have shown a functional variability of the amygdala’s response to stress in women with PMDD vs healthy controls.38,39 A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) study of the displays the possibility of an altered GABAergic function in patients with PMDD.40

Patients will PMDD have enhanced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reactivity when anticipating negative stimuli (but not to the actual exposure) during the luteal phase. A positive correlation between this reactivity and progesterone levels also was observed.41 Some researchers have suggested that prefrontal cortex dysfunction may be a risk factor for PMDD.42

HPA axis and HPG axis: Trauma, resiliency, inflammation. Altered cortisol levels (higher during the luteal phase43 and lower during times of stress14,44) suggest a possibly altered HPA axis in some women with PMDD. However, studies on this topic have been few and inconsistent.

Dysregulation of the HPG axis could cause vasomotor symptoms, sleep dysregulation, and mood symptoms during menopause; women with PMDD can also experience these symptoms. The influence of estrogen and progesterone on mood is also highly dependent on this axis.

Ultimately, the interplay between the HPA axis and the HPG axis is important. One study found that women with PMDD who had high serum ALLO levels (HPG-related) had blunted nocturnal cortisol levels (HPA-related) compared with healthy controls who had low ALLO levels.45

Significant stress and trauma exposure have been associated with PMDD. A study of 3,968 women found a history of trauma and PTSD were independently associated with PMDD.46 Another study of approximately 3,000 women found a strong correlation between abuse and PMS.47 However, a third study found no correlations between PMDD and trauma.48

Patients with a predisposition to PMDD may be more vulnerable to develop a posttraumatic stress-related disorder, perhaps due to decreased biologic resiliency. For example, the startle response (hypervigilance) has been shown to be different in women with PMDD. One study suggested that suboptimal production of premenstrual ALLO may lead to increased arousal and increased stress reactivity to psychosocial or environmental triggers.49

The possible role of inflammation in PMDD deserves further investigation. The luteal phase entails an increase in the production of proinflammatory markers.50,51 A 10-fold increase in progesterone is correlated with a 20% to 23% increase in C-reactive protein levels.52,53 Women with inflammatory diseases (eg, gingivitis or irritable bowel syndrome) show worsening of symptoms prior to menstruation.54-56 One study found increased levels of proinflammatory markers in women with PMDD compared with controls.57