Clinical trials: Bipolar mania. Researchers conducted a pooled analysis of two 12-week randomized trials comparing quetiapine with placebo in a mixed-age sample with bipolar mania.35 In a subgroup of 59 older patients (mean age, 62.9 years), manic symptoms improved significantly more with quetiapine (modal dose, 550 mg/d) than with placebo. Adverse effects reported by >10% of older patients were dry mouth, somnolence, postural hypotension, insomnia, weight gain, and dizziness. Insomnia was reported by >10% of patients receiving placebo.

In a case series of 11 elderly patients with mania receiving asenapine, Baruch et al36 reported a 63% remission rate. One patient discontinued the study because of a new rash, 1 discontinued after developing peripheral edema, and 3 patients reported mild sedation.

Beyer et al37 reported on a post hoc analysis of 94 older adults (mean age, 57.1 years; range, 50.1 to 74.8 years) with acute bipolar mania receiving olanzapine (n = 47), divalproex (n = 31), or placebo (n = 16) in a pooled olanzapine clinical trials database. Patients receiving olanzapine or divalproex had improvement in mania; those receiving placebo did not improve. Safety findings were comparable with reports in younger patients with mania.

Other clinical data. Adverse effects found in mixed-age samples using secondary analyses of clinical trials need to be interpreted with caution because these types of studies usually exclude individuals with significant medical comorbidity. Medical burden, cognitive impairment, or concomitant medications generally necessitate slower drug titration and lower total daily dosing. For example, a secondary analysis of the U.S. National Institute of Health-funded Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder study, which had broader inclusion criteria than most clinical trials, reported that, although recovery rates in older adults with bipolar disorder were fairly good (78.5%), lower doses of risperidone were used in older vs younger patients.38

Clinical considerations

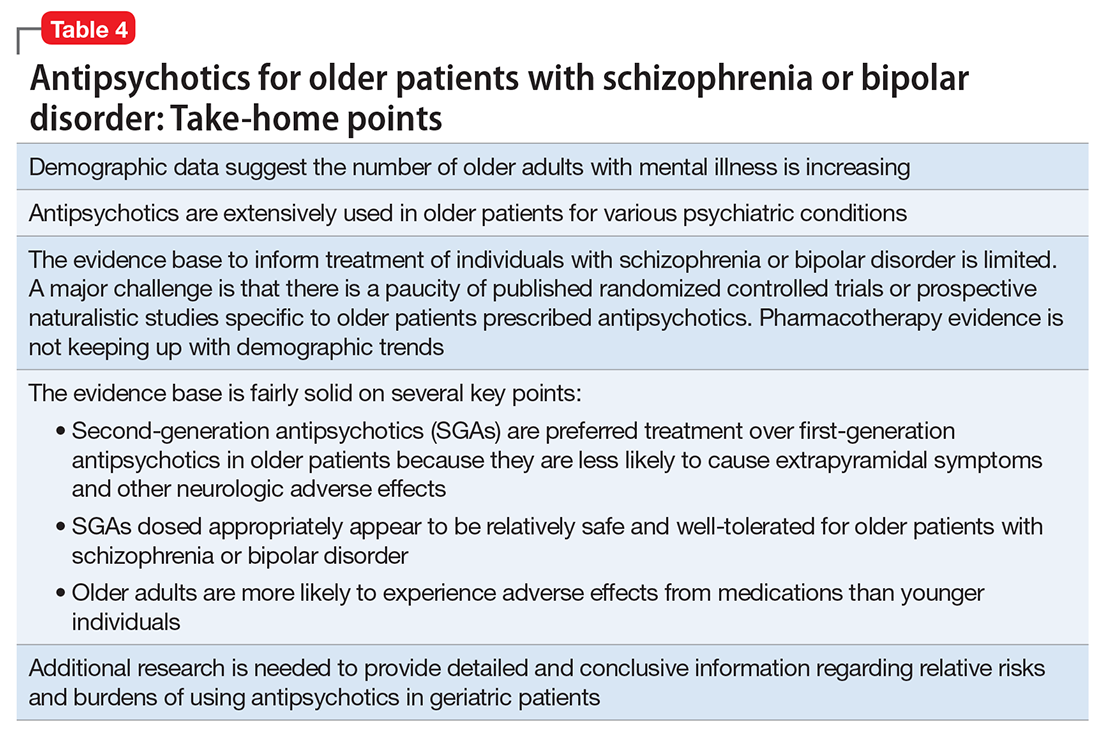

Interpretation of the relative risks of antipsychotics in older people must be tempered by the caveat that there is limited high-quality data (Table 4). Antipsychotics are the first-line therapy for older patients with schizophrenia, although their use is supported by a small number of prospective RCTs. SGAs are preferred because of their lower propensity to cause EPS and other motor adverse effects. Older persons with schizophrenia have an EPS threshold lower than younger patients and determining the lowest effective dosage may minimize EPS and cognitive adverse effects. As individuals with long-standing schizophrenia get older, their antipsychotic dosages may need to be reduced, and clinicians need to monitor for adverse effects that are more common among older people, such as tardive dyskinesia and metabolic abnormalities. In healthy, “younger” geriatric patients, monitoring for adverse effects may be similar to monitoring of younger patients. Patients who are older or frail may need more frequent assessment.

Like older adults with schizophrenia, geriatric patients with bipolar disorder have reduced drug tolerability and experience more adverse effects than younger patients. There are no prospective controlled studies that evaluated using antipsychotics in older patients with bipolar disorder. In older bipolar patients, the most problematic adverse effects of antipsychotics are akathisia, parkinsonism, other EPS, sedation and dizziness (which may increase fall risk), and GI discomfort. A key tolerability and safety consideration when treating older adults with bipolar disorder is the role of antipsychotics in relation to the use of lithium and mood stabilizers. Some studies have suggested that lithium has neuroprotective effects when used long-term; however, at least 1 report suggested that long-term antipsychotic treatment may be associated with neurodegeneration.39

The literature does not provide strong evidence on the many clinical variations that we see in routine practice settings, such as combinations of drug treatments or drugs prescribed to patients with specific comorbid conditions. There is a need for large cohort studies that monitor treatment course, medical comorbidity, and prognosis. Additionally, well-designed clinical trials such as the DART-AD, which investigated longer-term trajectories of people with dementia taking antipsychotics, should serve as a model for the type of research that is needed to better understand outcome variability among older people with chronic psychotic or bipolar disorders.40