The proportion of older adults in the world population is growing rapidly. In the next 10 to 15 years, the population age >60 will grow 3.5 times more rapidly than the general population.1 As a result, there is an increased urgency in examining benefits vs risks of antipsychotics in older individuals. In a 2010 U.S. nationally representative observational study, antipsychotic use was observed to rise slowly during early and middle adulthood, peaking at approximately age 55, declining slightly between ages 55 and 65, and then rising again after age 65, with >2% of individuals ages 80 to 84 receiving an antipsychotic.2 This is likely due to the chronology of psychotic, mood, and neurocognitive disorders across the life span. In this large national study, long-term antipsychotic treatment was common, and older patients were more likely to receive their prescriptions from non-psychiatrist physicians than from psychiatrists.2 Among patients receiving an antipsychotic, the proportion of those receiving it for >120 days was 54% for individuals ages 70 to 74; 49% for individuals ages 75 to 79; and 46% for individuals ages 80 to 84.

This 3-part review summarizes findings and risk–benefit considerations when prescribing antipsychotics to older individuals. Part 1 focused on those with chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder,3 and part 3 will cover patients with dementia. This review (part 2) aims to:

- briefly summarize the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and other major studies and analyses in older patients with major depressive disorder (MDD)

- provide a summative opinion on the relative risks and benefits associated with using antipsychotics in older adults with MDD

- highlight the gaps in the evidence base and areas that need additional research.

Summary of benefits, place in treatment armamentarium

The prevalence of MDD and clinically significant depressive symptoms in communitydwelling older adults is 3% to 4% and 15%, respectively, and as high as 16% and 50%, respectively, in nursing home residents.4 Because late-life depression is associated with suffering, disability, and excessive mortality, it needs to be recognized and treated aggressively.5 Antidepressants are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for late-life depression. Guidelines and expert opinion informed by the current evidence recommend using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as escitalopram or sertraline, as a first-line treatment; serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as duloxetine or venlafaxine, as a second-line treatment; and other antidepressants, such as bupropion or nortriptyline, as a third-line treatment.5,6 However, antipsychotics also have a role in treating late-life depression.

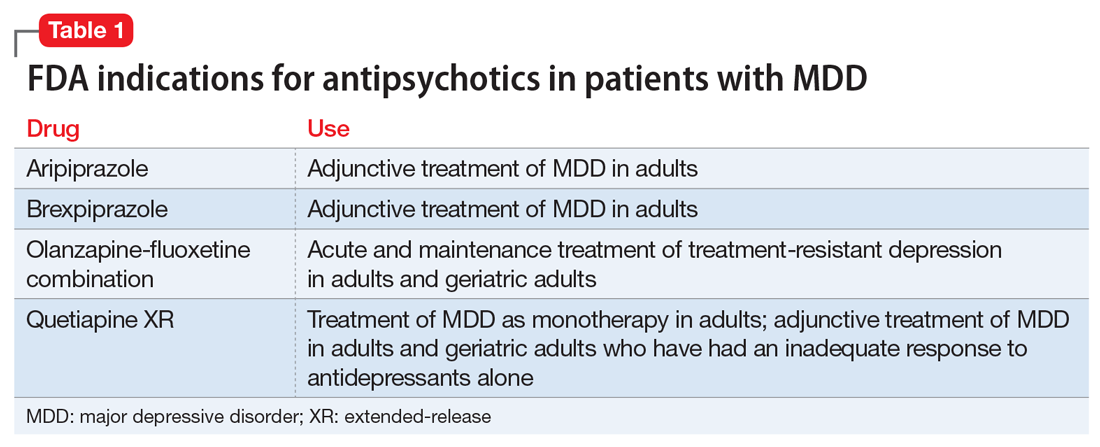

Over the past decade, several antipsychotics have been FDA-approved for treating MDD: aripiprazole and brexpiprazole as adjunctive treatment of MDD in adults; olanzapine-fluoxetine combination for acute and maintenance treatment of treatment-resistant depression in adults and geriatric adults; and quetiapine extended-release (XR) as monotherapy for MDD in adults and as adjunctive treatment of MDD in adults and geriatric adults who have had an inadequate response to antidepressants alone (Table 1). However, “black-box” warnings for all first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and SGAs alert clinicians that these medications have been associated with serious adverse events in older adults with dementia, including “deaths […] due to heart-related events (eg, heart failure, sudden death) or infections (mostly pneumonia),” with 15 of 17 placebo-controlled trials showing a higher number of deaths with an antipsychotic compared with placebo.7 Although similar controlled data on the mortality risk of antipsychotics in older adults with mood disorders do not exist, most experts limit their use to 2 groups of older patients: those with MDD and psychotic features (“psychotic depression”) and those with treatment-resistant depression.

Data from several rigorously conducted RCTs support using an antidepressant plus an FGA or SGA as first-line pharmacotherapy in younger and older patients with “psychotic depression.”8-12 SGAs also can be used as augmenting agents when there is only a partial response to antidepressants.13-15 In this situation, guidelines and experts favor an augmentation strategy over switching to another antidepressant.5,9,10,16 Until recently, most published pharmacologic trials for late-life treatment-resistant depression supported using lithium to augment antidepressants.14,17 However, because several antipsychotics are now FDA-approved for treating MDD, and in light of positive findings from several studies relevant to older patients,18-21 many experts now support using SGAs to augment antidepressants in older patients with nonpsychotic depression.5,15