Prevalence of DDM in psychiatric disorders

The successful treatment of DDM with dopaminergic drugs is meaningful because of the coexistence of DDM in various neuropsychiatric conditions. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), disturbances in the dopaminergic system may explain the high comorbidity of apathy, which ranges from 47% in mild AD to 80% in moderate AD.33 In the dopamine-reduced states of cocaine and amphetamine withdrawal, 67% of patients report apathy and lack of motivation.8,34 Additionally, the prevalence of apathy is reported at 27% in Parkinson’s disease, 43% in mild cognitive impairment, 70% in mixed dementia, 94% in a major depressive episode, and 53% in schizophrenia.35 In schizophrenia with predominately negative symptoms, in vivo and postmortem studies have found reduced dopamine receptors.8 Meanwhile, the high rate of akinetic mutism in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease allows for its use as a reliable diagnostic criteria in this disorder.36

However, the prevalence of DDM is best documented as it relates to stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI). For instance, after experiencing a stroke, 20% to 25% of patients suffer from apathy.37 Many case reports describe abulia and akinetic mutism after cerebral infarction or hemorrhage, although the incidence of these disorders is unknown.2,38-40 Apathy following TBI is common, especially in younger patients who have sustained a severe injury.41 One study evaluated the prevalence of apathy after TBI among 83 consecutive patients in a neuropsychiatric clinic. Of the 83 patients, 10.84% had apathy without depression, and an equal number were depressed without apathy; another 60% of patients exhibited both apathy and depression. Younger patients (mean age, 29 years) were more likely to be apathetic than older patients, who were more likely to be depressed or depressed and apathetic (mean age, 42 and 38 years, respectively).41 Interestingly, DDM often are associated with cerebral lesions in distinct and distant anatomical locations that are not clearly connected to the neural circuits of motivational pathways. This phenomenon may be explained by the concept of diaschisis, which states that injury to one part of an interconnected neural network can affect other, separate parts of that network.2 If this concept is accurate, it may broaden the impact of DDM, especially as it relates to stroke and TBI.

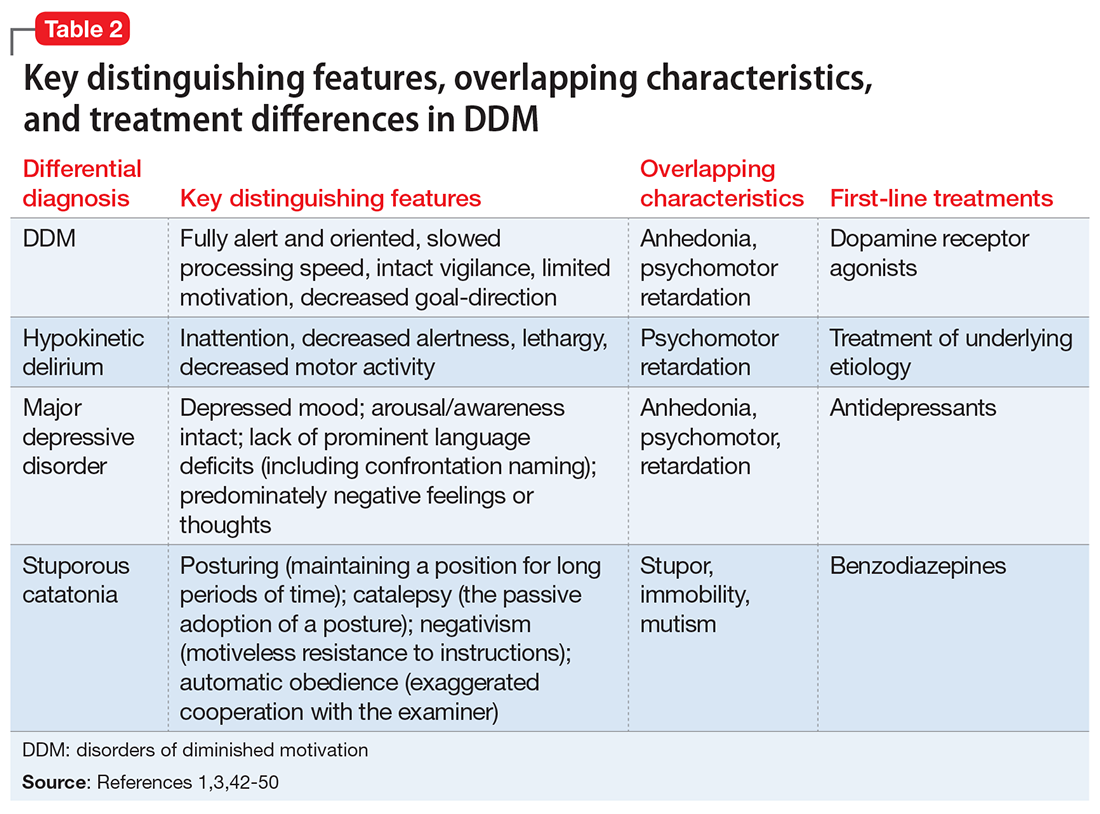

The differential diagnosis of DDM includes depression and hypokinetic delirium (Table 21,3,42-50). A potential overlapping but confounding condition is stuporous catatonia, with symptoms that include psychomotor slowing such as immobility, staring, and stupor.47 It is important to differentiate these disorders because the treatment for each differs. As previously discussed, there is a clear role for dopamine receptor agonists in the treatment of DDM.

Although major depressive disorder can be treated with medications that increase dopaminergic transmission, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are more commonly used as first-line agents.44 However, an SSRI would theoretically be contraindicated in DDM, because increased serotonin transmission decreases dopamine release from the midbrain, and therefore an SSRI may not only result in a lack of improvement but may worsen DDM.48 Finally, although delirium is treated with atypical or conventional antipsychotics vis-a-vis dopamine type 2 receptor antagonism,45 stuporous catatonia is preferentially treated with gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptor agonists such as lorazepam.50

What to do when your patient’s presentation suggests DDM

Assessment of DDM should be structured, with input from the patient and the caregiver, and should incorporate the physician’s perspective. A history should be obtained applying recent criteria of apathy. The 3 core domains of apathy—behavior, cognition, and emotion—need to be evaluated. The revised criteria are based on the premise that change in motivation can be measured by examining a patient’s responsiveness to internal or external stimuli. Therefore, each of the 3 domains includes 2 symptoms: (1) self-initiated or “internal” behaviors, cognitions, and emotions (initiation symptom), and (2) the patient’s responsiveness to “external” stimuli (responsiveness symptom).51

One of the main diagnostic dilemmas is how to separate DDM from depression. The differentiation is difficult because of substantial overlap in the manifestation of key symptoms, such as a lack of interest, anergia, psychomotor slowing, and fatigue. Caregivers often mistakenly describe DDM as a depressive state, even though a lack of sadness, desperation, crying, and a depressive mood distinguish DDM from depression. Usually, DDM patients lack negative thoughts, emotional distress, sadness, vegetative symptoms, and somatic concerns, which are frequently observed in mood disorders.51

Several instruments have been developed for assessing neuropsychiatric symptoms. Some were specifically designed to measure apathy, whereas others were designed to provide a broader neuropsychiatric assessment. The NPI is the most widely used multidimensional instrument for assessing neuropsychiatric functioning in patients with neurocognitive disorders (NCDs). It is a valid, reliable instrument that consists of an interview of the patient’s caregiver. It is designed to assess the presence and severity of 10 symptoms, including apathy. The NPI includes both apathy and depression items, which can help clinicians distinguish the 2 conditions. Although beyond the scope of this article, more recent standardized instruments that can assess DDM include the Apathy Inventory, the Dementia Apathy Interview and Rating, and the Structured Clinical Interview for Apathy.52

As previously mentioned, researchers have proposed that DDM are simply a continuum of severity of reduced behavior, and akinetic mutism may be the extreme form. The dilemma is how to formally diagnose states of abulia and akinetic mutism, given the lack of diagnostic criteria and paucity of standardized instruments. Thus, distinguishing between abulia and akinetic mutism (and apathy) is more of a quantitative than qualitative exercise. One could hypothesize that higher scores on a standardized scale to measure apathy (ie, NPI) could imply abulia or akinetic mutism, although to the best of our knowledge, no formal “cut-off scores” exist.53

Treatment of apathy. The duration of pharmacotherapy to treat apathy is unknown and their usage is off-label. Further studies, including double-blind, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are needed. Nonetheless, the 2 classes of medications that have the most evidence for treating apathy/DDM are psychostimulants and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs).

AChEIs are primarily used for treating cognitive symptoms in NCDs, but recent findings indicate that they have beneficial effects on noncognitive symptoms such as apathy. Of all medications used to treat apathy in NCDs, AChEIs have been used to treat the largest number of patients. Of 26 studies, 24 demonstrated improvement in apathy, with 21 demonstrating statistical significance. These studies ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 1 year, and most were open-label.54

Five studies (3 RCTs and 2 open-label studies) assessed the efficacy of methylphenidate for treating apathy due to AD. All the studies demonstrated at least some benefit in apathy scores after treatment with methylphenidate. These studies ranged from 5 to 12 weeks in duration. Notably, some patients reported adverse effects, including delusions and irritability.54

Although available evidence suggests AChEIs may be the most effective medications for treating apathy in NCDs, methylphenidate has been demonstrated to work faster.55 Thus, in cases where apathy can significantly affect activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living, a quicker response may dictate treatment with methylphenidate. It is imperative to note that safety studies and more large-scale double-blind RCTs are needed to further demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of methylphenidate.

Published in 2007, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines56 state that psychostimulants are a possible treatment option for patients with severe apathy. At the same time, clinicians are reminded that these agents—especially at higher doses—can produce various problematic adverse effects, including tachycardia, hypertension, restlessness, dyskinesia, agitation, sleep disturbances, psychosis, confusion, and decreased appetite. The APA guidelines recommend using low initial doses, with slow and careful titration. For example, methylphenidate should be started at 2.5 to 5 mg once in the morning, with daily doses not to exceed 30 to 40 mg. In our clinical experience, doses >20 mg/d have not been necessary.57

Treatment of akinetic mutism and abulia. In patients with akinetic mutism and possible abulia, for whom oral medication administration is either impossible or contraindicated (ie, due to the potential risk of aspiration pneumonia), atypical antipsychotics, such as IM olanazapine, have produced a therapeutic response in apathetic patients with NCD. However, extensive use of antipsychotics in NCD is not recommended because this class of medications has been associated with serious adverse effects, including an increased risk of death.55

Bottom Line

Apathy, abulia, and akinetic mutism have been categorized as disorders of diminished motivation (DDM). They commonly present after a stroke or traumatic brain injury, and should be differentiated from depression, hypokinetic delirium, and stuporous catatonia. DDM can be successfully treated with dopamine agonists.

Related Resources

- Barnhart WJ, Makela EH, Latocha MJ. SSRI-induced apathy syndrome: a clinical review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(3):196-199.

- Dell’Osso B, Benatti B, Altamura AC, et al. Prevalence of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-related apathy in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(6):725-726.

- D’Souza G, Kakoullis A, Hegde N, et al. Recognition and management of abulia in the elderly. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2010;14(6):24-28.

Drug Brand Names

Bromocriptine • Parlodel

Bupropion • Wellbutrin XL, Zyban

Carbidopa • Lodosyn

Dexamethasone • DexPak, Ozurde

Donepezil • Aricept

Levodopa/benserazide • Prolopa

Levodopa/carbidopa • Pacopa Rytary Sinemet

Lorazepam • Ativan

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Methylin

Metronidazole • Flagyl, Metrogel

Modafinil • Provigil

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Ropinirole • Requip

Rotigotine • Neurpro

Scopolamine • Transderm Scop

Ziprasidone • Geodon