Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking risperidone, 3 mg/d, lamotrigine, 200 mg/d, metformin, 2,000 mg/d, medroxyprogesterone, 150 mg every 3 months, and prazosin, 8 mg/d. Her mood has been stabilized for the last 3 years with this medication regimen.

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

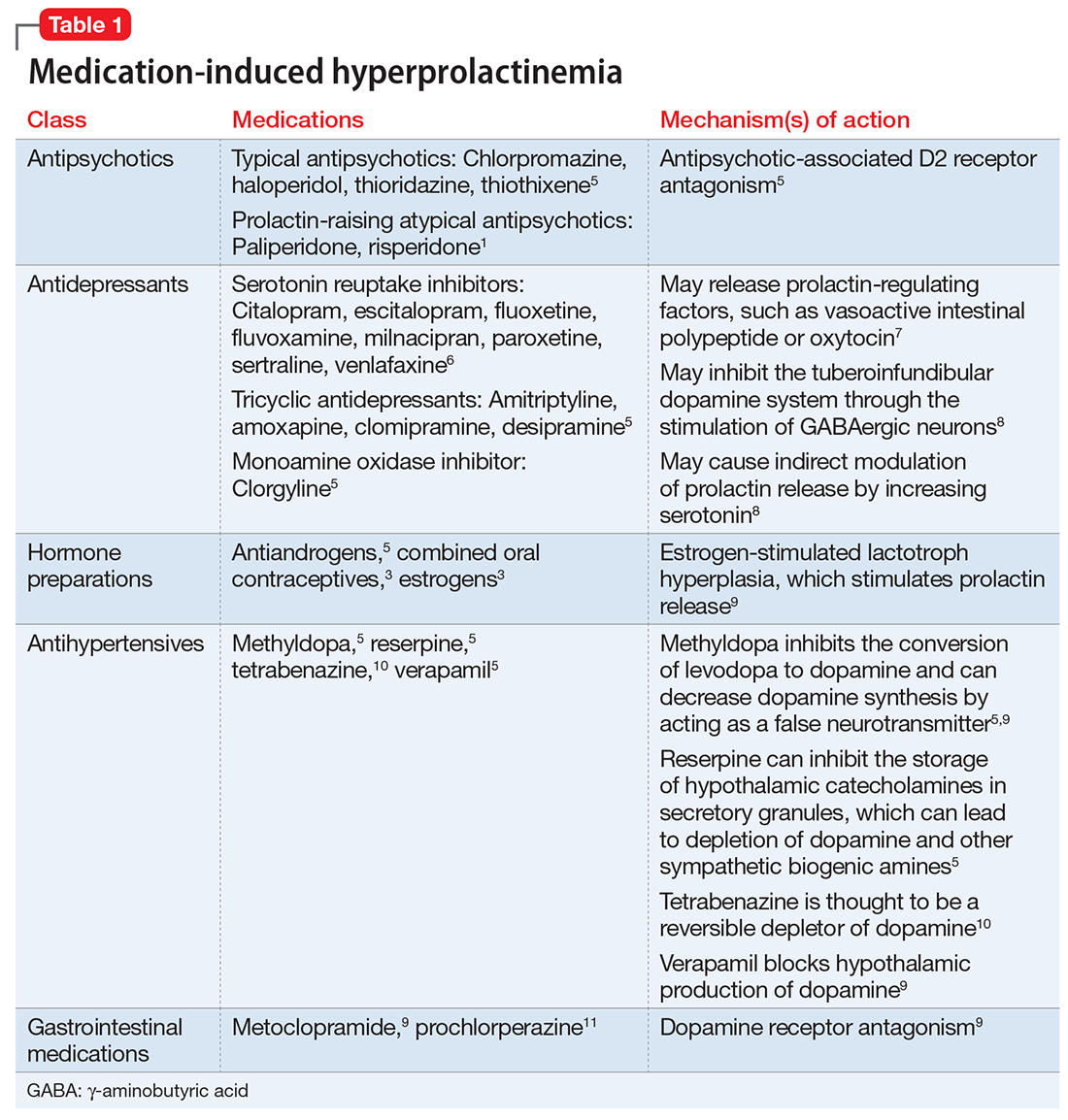

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17