CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

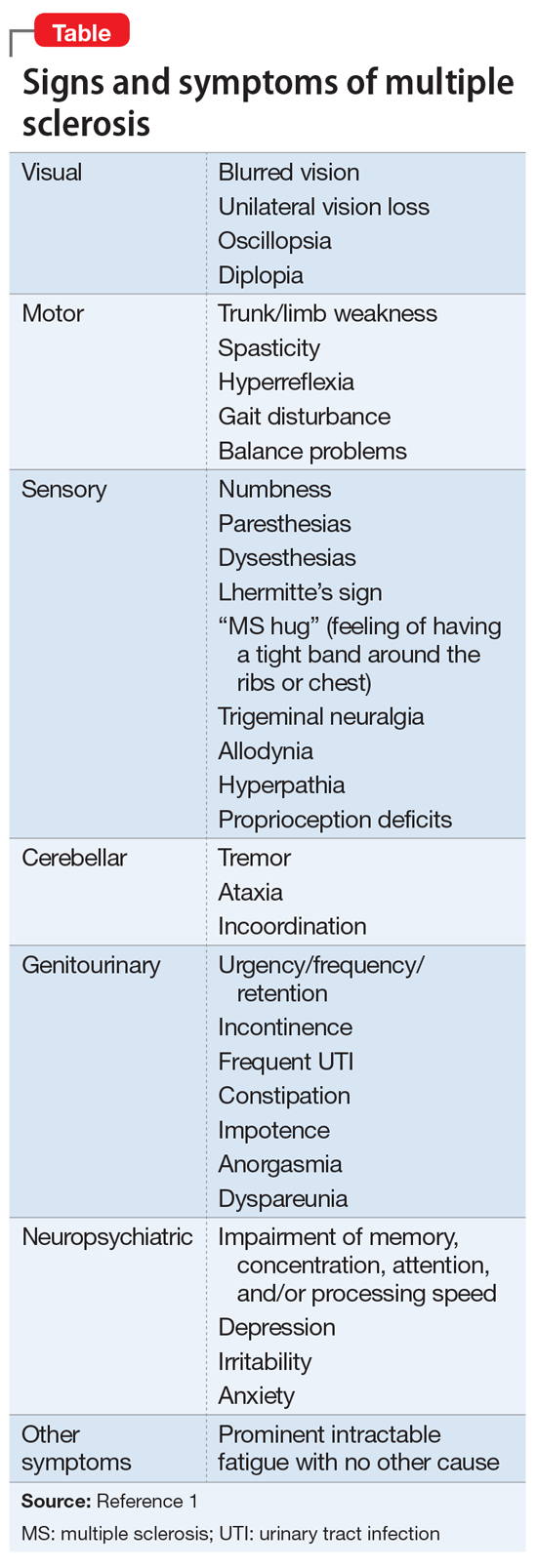

While MS is defined by neurologic episodes resulting from CNS demyelination (Table1), psychiatric symptoms are also highly prevalent in patients with MS but can be overlooked in clinical settings. MDD seems to be particularly common, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 50% in patients with MS,2,3 along with a lifetime prevalence of suicide 7.5 times higher than in the general population.4 Some studies have found that depressive symptoms supersede physical disability and cognitive dysfunction as significant determinants of quality of life in MS patients.5 Additionally, in patients with MS, bipolar disorder and psychosis have a lifetime prevalence 2 to 3 times that of the general population.2 While past literature has described a subgroup of patients with MS who present with euphoria as the predominant mood state, contemporary researchers regard this presentation as rare and most likely reflecting a change in the definition of euphoria over the past century.6 Although MDD is the most prevalent and most studied MS-associated psychiatric diagnosis, other mood symptoms can be similarly disruptive to daily functioning. Therefore, early recognition and management of psychiatric manifestations in patients with MS is essential, because psychiatric conditions such as depression can predict morbidity, treatment adherence, and overall quality of life.7

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...