For many years now, we have been lamenting the shortage of psychiatrists practicing in the United States. At this point, we must identify possible solutions.1,2 Currently, the shortage of practicing psychiatrists in the United States could be as high as 45,000.3 The major problem is that the number of psychiatry residency positions will not increase in the foreseeable future, thus generating more psychiatrists is not an option.

Medicare pays about $150,000 per residency slot per year. To solve the mental health access problem, $27 billion (45,000 x $150,000 x 4 years)* would be required from Medicare, which is not feasible.4 The national average starting salary for psychiatrists from 2018-2019 was about $273,000 (much lower in academic institutions), according to Merritt Hawkins, the physician recruiting firm. That salary is modest, compared with those offered in other medical specialties. For this reason, many graduates choose other lucrative specialties. And we know that increasing the salaries of psychiatrists alone would not lead more people to choose psychiatry. On paper, it may say they work a 40-hour week, but they end up working 60 hours a week.

To make matters worse, family medicine and internal medicine doctors generally would rather not deal with people with mental illness and do “cherry-picking and lemon-dropping.” While many patients present to primary care with mental health issues, lack of time and education in psychiatric disorders and treatment hinder these physicians. In short, the mental health field cannot count on primary care physicians.

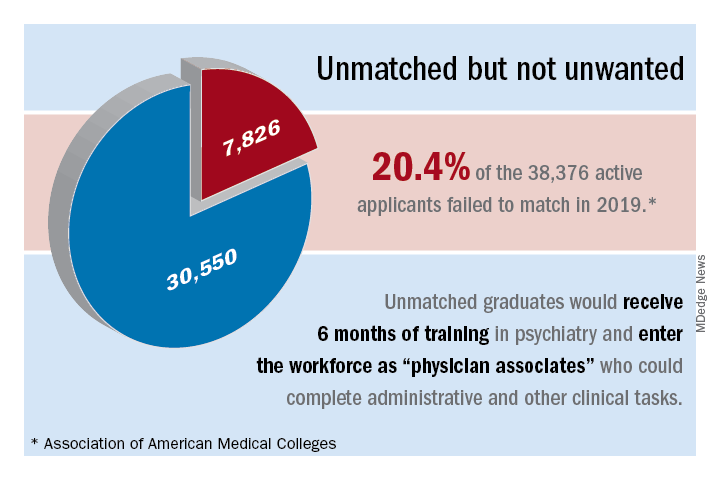

Meanwhile, there are thousands of unmatched residency graduates. In light of those realities, perhaps psychiatry residency programs could provide these unmatched graduates with 6 months of training and use them to supplement the workforce. These medical doctors, or “physician associates,” could be paired with a few psychiatrists to do clinical and administrative work. With one in four individuals having mental health issues, and more and more people seeking help because of increasing awareness and the benefits that accompanied the Affordable Care Act (ACA), physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists so that they can deliver better care to more people. We must take advantage of these two trends: The surge in unmatched graduates and “shrinking shrinks,” or the decline in the psychiatric workforce pool. (The Royal College of Physicians has established a category of clinicians called physician associates,5 but they are comparable to physician assistants in the United States. As you will see, the construct I am proposing is different.)

The current landscape

Currently, psychiatrists are under a lot of pressure to see a certain number of patients. Patients consistently complain that psychiatrists spend a maximum of 15 minutes with them, that the visits are interrupted by phone calls, and that they are not being heard and helped. Burnout, a silent epidemic among physicians, is relatively prevalent in psychiatry.6 Hence, some psychiatrists are reducing their hours and retiring early. Psychiatry has the third-oldest workforce, with 59% of current psychiatrists aged 55 years or older.7 A better pay/work ratio and work/life balance would enable psychiatrists to enjoy more fulfilling careers.

Many psychiatrists are spending a lot of their time in research, administration, and the classroom. In addition to those issues, the United States currently has a broken mental health care system.8 Finally, the medical practice landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, and those changes undermine both the effectiveness and well-being of clinicians.

The historical landscape

Some people proudly refer to the deinstitutionalization of mental asylums and state mental hospitals in the United States. But where have these patients gone? According to a U.S. Justice Department report, 2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in U.S. federal and state prisons and county jails in 2013.9 In addition, 4,751,400 adults in 2013 were on probation or parole. The percentages of inmates in state and federal prisons and local jails with a psychiatric diagnosis were 56%, 45%, and 64%, respectively.

I work at the Maryland correctional institutions, part of the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. One thing that I consistently hear from several correctional officers is “had these inmates received timely help and care, they wouldn’t have ended up behind bars.” Because of the criminalization of mental illness, in 44 states, the number of people with mental illness is higher in a jail or prison than in the largest state psychiatric hospital, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. We have to be responsible for many of the inmates currently in correctional facilities for committing crimes related to mental health problems. In Maryland, a small state, there are 30,000 inmates in jails, and state and federal prison. The average cost of a meal is $1.36, thus $1.36 x 3 meals x 30,000 inmates = $122,400.00 for food alone for 1 day – this average does not take other expenses into account. By using money and manpower wisely and taking care of individuals’ mental health problems before they commit crimes, better outcomes could be achieved.

I used to work for MedOptions Inc. doing psychiatry consults at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists and nurse practitioners, especially in the suburbs and rural areas, those patients could not be seen in a timely manner even for their 3-month routine follow-ups. As my colleagues and I have written previously, many elderly individuals with major neurocognitive disorders are not on the Food and Drug Administration–approved cognitive enhancers, such as donepezil, galantamine, and memantine.10 Instead, those patients are on benzodiazepines, which are associated with cognitive impairments, and increased risk of pneumonia and falls. Benzodiazepines also can cause and/or worsen disinhibited behavior. Also, in those settings, crisis situations often are addressed days to weeks later because of the doctor shortage. This situation is going to get worse, because this patient population is growing.

Child and geriatric psychiatry shortages

Child and geriatric psychiatrist shortages are even higher than those in general psychiatry.11 Many years of training and low salaries are a few of the reasons some choose not to do a fellowship. These residency graduates would rather join a practice at an attending salary than at a fellow’s salary, which requires an additional 1 to 2 years of training. Student loans of $100,000–$500,000 after residency also discourage some from pursuing fellowship opportunities. We need to consider models such as 2 years of residency with 2 years of a child psychiatry fellowship or 3 years of residency with 1 year of geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Working as an adult attending physician (50% of the time) and concurrently doing a fellowship (50% of the time) while receiving an attending salary might motivate more people to complete a fellowship.

In specialties such as radiology, international medical graduates (IMGs) who have completed residency training in radiology in other countries can complete a radiology fellowship in a particular area for several years and can practice in the United States as board-eligible certified MDs. Likewise, in line with the model proposed here, we could provide unmatched graduates who have no residency training with 3 to 4 years of child psychiatry and geriatric psychiatry training in addition to some adult psychiatry training.

Implementation of such a model might take care of the shortage of child and geriatric psychiatrists. In 2015, there were 56 geriatric psychiatry fellowship programs; 54 positions were filled, and 51 fellows completed training.12 “It appears that a reasonable percentage of IMGs who obtain a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry do not have an intent of pursuing a career in the field,” Marc H. Zisselman, MD, former geriatric psychiatry fellowship director and currently with the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, told me in 2016. These numbers are not at all sufficient to take care of the nation’s unmet need. Hence, implementing alternate strategies is imperative.

Administrative tasks and care

What consumes a psychiatrist’s time and leads to burnout? The answer has to do with administrative tasks at work. Administrative tasks are not an effective use of time for an MD who has spent more than a decade in medical school, residency, and fellowship training. Although electronic medical record (EMR) systems are considered a major advancement, engaging in the process throughout the day is associated with exhaustion.

Many physicians feel that EMRs have slowed them down, and some are not well-equipped to use them in quick and efficient ways. EMRs also have led to physicians making minimal eye contact in interviews with patients. Patients often complain: “I am talking, and the doctor is looking at the computer and typing.” Patients consider this behavior to be unprofessional and rude. In a survey of 57 U.S. physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics, results showed that during the work day, 27% of their time was spent on direct clinical face time with patients and 49.2% was spent on EMR and desk work. While in the examination room with patients, physicians spent 52.9% of their time on direct clinical face time and 37.0% on EMR and desk work. Outside office hours, physicians spend up to 2 hours of personal time each night doing additional computer and other clerical work.13

Several EMR software systems, such as CareLogic, Cerner, Epic,NextGen, PointClickCare, and Sunrise, are used in the United States. The U.S. Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) use the computerized patient record system (CPRS) across the country. VA clinicians find CPRS extremely useful when they move from one VAMC to another. Likewise, hospitals and universities may use one software system such as the CPRS and thus, when clinicians change jobs, they find it hard to adapt to the new system.

Because psychiatrists are wasting a lot of time doing administrative tasks, they might be unable to do a good job with regard to making the right diagnoses and prescribing the best treatments.When I ask patients what are they diagnosed with, they tell me: “It depends on who you ask,” or “I’ve been diagnosed with everything.” This shows that we are not doing a good job or something is not right.

Currently, psychiatrists do not have the time and/or interest to make the right diagnoses and provide adequate psychoeducation for their patients. This also could be attributable to a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, time constraints, cynicism, and apathy. Time constraints also lead to the gross underutilization14 of relapse prevention strategies such as long-acting injectables and medications that can prevent suicide, such as lithium and clozapine.15

Other factors that undermine good care include not participating in continuing medical education (CME) and not staying up to date with the literature. For example, haloperidol continues to be one of the most frequently prescribed (probably, the most common) antipsychotic, although it is clearly neurotoxic16,17 and other safer options are available.18 Board certification and maintenance of certification (MOC) are not synonymous with good clinical practice. Many physicians are finding it hard to complete daily documentation, let alone time for MOC. For a variety of reasons, many are not maintaining certification, and this number is likely to increase. Think about how much time is devoted to the one-to-one interview with the patient and direct patient care during the 15-minute medical check appointment and the hour-long new evaluation. In some clinics, psychiatrists are asked to see more than 25 patients in 4 hours. Some U.S.-based psychiatrists see 65 inpatients and initiate 10 new evaluations in a single day. Under those kinds of time constraints, how can we provide quality care?