For Ms. T’s case, civil commitment and involuntary medication hearings are held in probate court, which is a civil (not criminal) court. In addition to overseeing civil commitment and involuntary medications, probate courts adjudicate will and estate contests, conservatorship, and guardianship. Conservatorship hearings deal with financial issues, and guardianship cases encompass personal and health-related needs. Regardless of the court, an individual is guaranteed due process under the 5th Amendment (federal) and 14th Amendment (state).

Individuals are presumed competent to make their own decisions, but a court may call this into question. Competencies are specific to a variety of areas, such as criminal proceedings, medical decision making, writing a will (testimonial capacity), etc. Because each field applies its own standard of competence, an individual may be competent in one area but incompetent in another. Competence in medical decision making varies by state but generally consists of being able to communicate a choice, understand relevant information, appreciate one’s illness and its likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information.8

Box

Administering medications despite a patient’s objection differs from situations in which medications are provided during a psychiatric emergency. In an emergency, courts do not have time to weigh in. Instead, emergency medications (most often given as IM injections) are administered based on the physician’s clinical judgment. The criteria for psychiatric emergencies are delineated at the state level, but typically are defined as when a person with a mental illness creates an imminent risk of harm to self or others. Alternative approaches to resolving the emergency may include verbal de-escalation, quiet time in a room devoid of stimuli, locked seclusion, or physical restraints. These measures are often exhausted before emergency medications are administered.

Source: Reference 9

It is important to note that the legal process required before administering involuntary medications is distinct from situations in which medication needs to be provided during a psychiatric emergency. The Box9 outlines the difference between these 2 scenarios.

4 Legal models

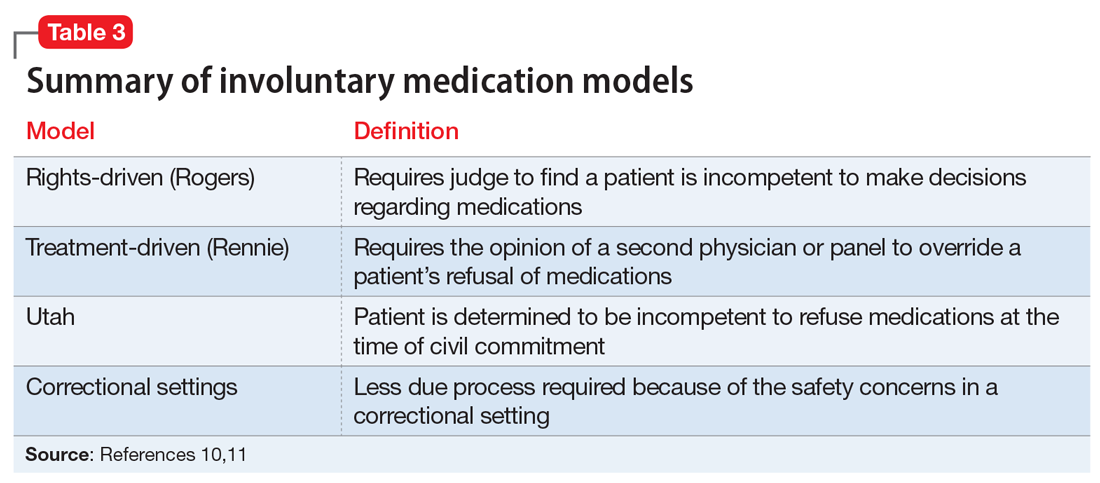

There are several legal models used to determine when a patient can be administered psychiatric medications over objection. Table 310,11 summarizes these models.

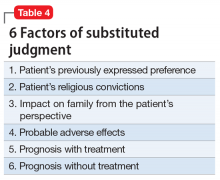

Rights-driven (Rogers) model. If Ms. T was involuntarily hospitalized in Massachusetts or another state that adopted the rights-driven model, she would retain the right to refuse treatment. These states require an external judicial review, and court approval is necessary before imposing any therapy. This model was established in Rogers v Commissioner,12 where 7 patients at the Boston State Hospital filed a lawsuit regarding their right to refuse medications. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, despite being involuntarily committed, a patient is considered competent to refuse treatment until found specifically incompetent to do so by the court. If a patient is found incompetent, the judge, using a full adversarial hearing, decides what the incompetent patient would have wanted if he/she were competent. The judge reaches a conclusion based on the substituted judgment model (Table 410). In Rogers v Commissioner,12 the court ruled that the right to decision making is not lost after becoming a patient at a mental health facility. The right is lost only if the patient is found incompetent by the judge. Thus, every individual has the right to “manage his own person” and “take care of himself.”

Continue to: An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model