There is no single guideline on how and when a neuropsychology referral is warranted.22 Insurance coverage for neurocognitive testing varies. Regardless of formal referral to neuropsychology, assessment of cognitive function is an important aspect of SRC management and is a factor in return-to-school and return-to-play decisions.3,22 Screening tools, such as the SCAT5, are useful in acute and subacute settings (ie, up to 3 to 5 days after injury); clinicians often use serial monitoring to track the resolution of symptoms.3 If pre-season baseline cognitive test results are available, clinicians may compare them to post-SRC results, but this should not be the sole basis of management decisions.3,22

Diagnosing psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC

Diagnosis of psychiatric symptoms and disorders associated with SRC can be challenging.7 There are no concussion-specific rating scales or diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders unique to patients who have sustained SRC. As a result, clinicians are left to use standard DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with SRC. Importantly, psychiatric symptoms must be distinguished from disorders. For example, Kontos et al23 reported significantly worse depressive symptoms following SRC, but not at the level to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. This is an important distinction, because a psychiatrist might be less likely to initiate pharmacotherapy for a patient with SRC who has only a few depressive symptoms and is only 1 week post-SRC, vs for one who has had most symptoms of a major depressive episode for several weeks.

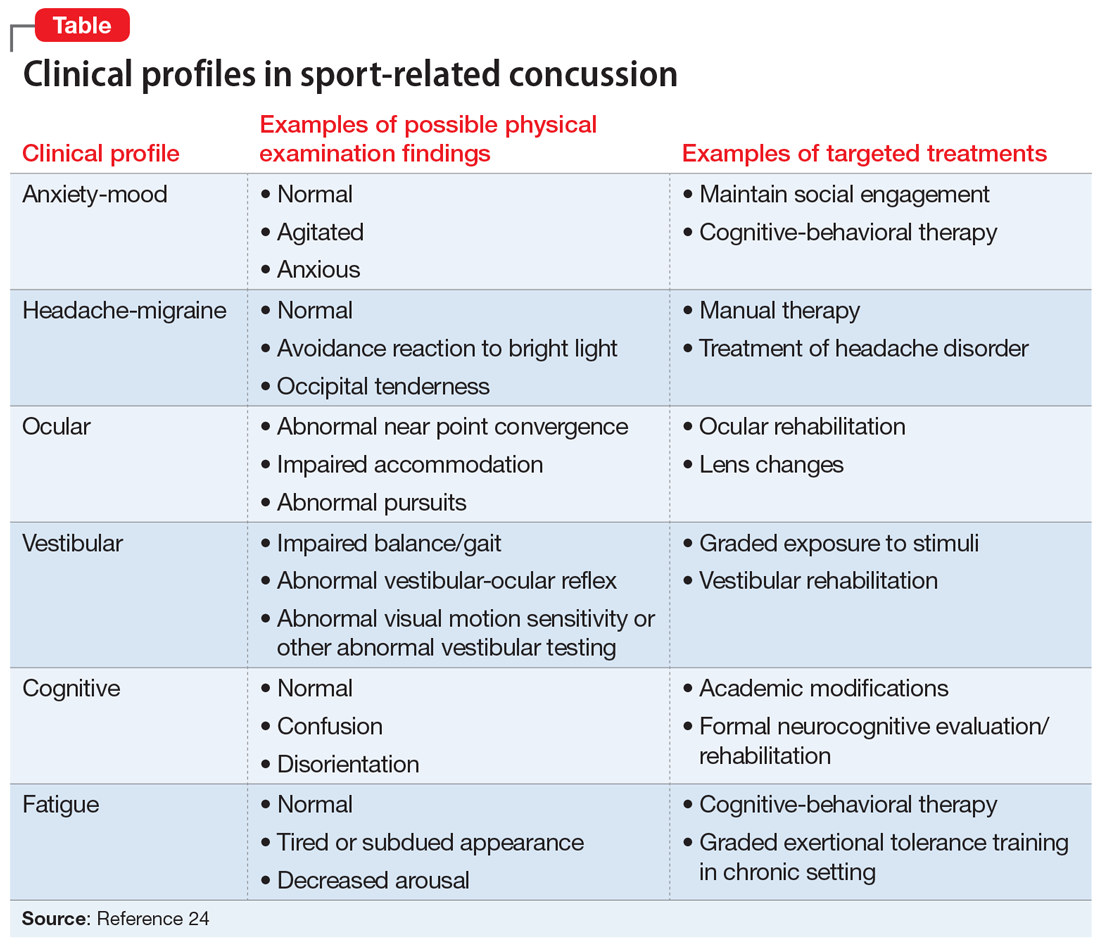

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has proposed 6 overlapping clinical profiles in patients with SRC (see the Table).24 Most patients with SRC have features of multiple clinical profiles.24 Anxiety/mood is one of these profiles. The impetus for developing these profiles was the recognition of heterogeneity among concussion presentations. Identification of the clinical profile(s) into which a patient’s symptoms fall might allow for more specific prognostication and targeted treatment.24 For example, referral to a psychiatrist obviously would be appropriate for a patient for whom anxiety/mood symptoms are prominent.

Treatment options for psychiatric sequelae of SRC

Both psychosocial and medical principles of management of psychiatric manifestations of SRC are important. Psychosocially, clinicians should address factors that may contribute to delayed SRC recovery (Box 225-30).

Box 2

- Recommend a progressive increase in exercise after a brief period of rest (often ameliorates psychiatric symptoms, as opposed to the historical approach of “cocoon therapy” in which the patient was to rest for prolonged periods of time in a darkened room so as to minimize brain stimulation)25

- Allow social activities, including team meetings (restriction of such activities has been associated with increased post-SRC depression)26

- Encourage members of the athlete’s “entourage” (team physicians, athletic trainers, coaches, teammates, and parents) to provide support27

- Educate coaches and teammates about how to make supportive statements because they often have trouble knowing how to do so27

- Recommend psychotherapy for mental and other physical symptoms of SRC that are moderate to severe or that persist longer than 4 weeks after the SRC28

- Recommend minimization of use of alcohol and other substances29,30

SRC: sport-related concussion

No medications are FDA-approved for SRC or associated psychiatric symptoms, and there is minimal evidence to support the use of specific medications.31 Most athletes with SRC recover quickly—typically within 2 weeks—and do not need medication.4,32 When medications are needed, start with low dosing and titrate slowly.33,34

Continue to: For patients with SRC who experience insomnia...