Mr. N, age 55, has a long, documented history of schizophrenia. His overall baseline functioning has been poor because he is socially isolated, does not work, and lives in subsidized housing paid for by the county where he lives. His psychosocial circumstances have limited his ability to afford or otherwise obtain nutritious food or participate in any type of regular exercise program. He has been maintained on olanzapine, 20 mg nightly, for the past 5 years. During the past year, his functioning and overall quality of life have declined even further after he was diagnosed with hypertension. Mr. N’s in-office blood pressure was 160/95 mm Hg (normal range: systolic blood pressure, 90 to 120 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure, 60 to 80 mm Hg). He says his primary care physician informed him that he is pre-diabetic after his hemoglobin A1c came back at 6.0 mg/dL (normal range <5.7 mg/dL) and his body mass index was 32 kg/m2 (normal range 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). Currently, Mr. N’s psychiatric symptoms are stable, but his functional decline is now largely driven by metabolic parameters. Along with lifestyle changes and nonpharmacologic interventions, what else should you consider to help him?

In addition to positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, schizophrenia is accompanied by disturbances in metabolism,1 inflammatory markers,2 and sleep/wake cycles.3 Current treatment strategies focus on addressing symptoms and functioning, but the metabolic and inflammatory targets that account for significant morbidity and mortality remain largely unaddressed.

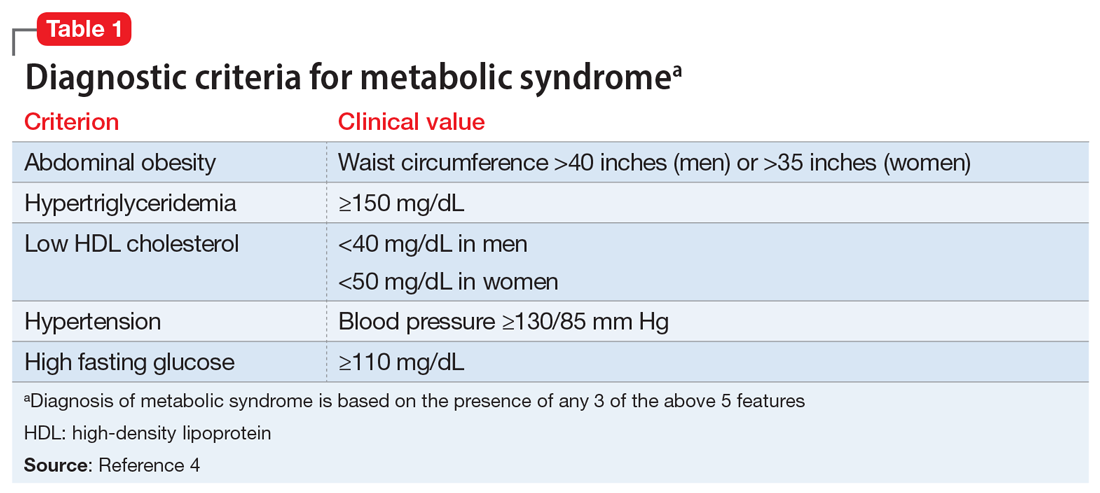

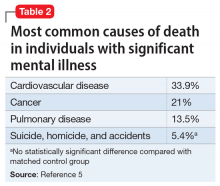

Some patients with schizophrenia meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions—including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension—that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Table 14). Metabolic syndrome and its related consequences are a major barrier to the successful treatment of patients with schizophrenia, and lead to increased mortality. Druss et al5 found that individuals with significant mental illness died on average 8.2 years earlier than age-matched controls. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (Table 25).

“Off-label” prescribing has been used in an attempt to delay or treat emerging metabolic syndrome in individuals with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, comprehensive strategies with a uniform application in clinical settings remain elusive. In this article, we review 3 off-label agents—metformin, topiramate, and melatonin—that may be used to address weight gain and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia.

Metformin

Metformin is an oral medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It works by decreasing glucose absorption, suppressing gluconeogenesis in the liver, and increasing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. It was FDA-approved for use in the United States in 1994. In addition to improving glucose homeostasis, metformin has also been associated with decreased body mass index (BMI), triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in individuals at risk for diabetes.6

Recent consensus guidelines suggest that metformin has sufficient evidence to support its clinical use for preventing or treating antipsychotic-induced weight gain.7 A meta-analysis that included >40 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) found that metformin8-11:

- reduces antipsychotic-induced weight gain (approximately 3 kg, up to 5 kg in patients with first-episode psychosis)

- reduces fasting glucose levels, hemoglobin A1c, fasting insulin levels, and insulin resistance

- leads to a more favorable lipid profile (reduced triglycerides, LDL, and total cholesterol, and increased HDL).

Not surprisingly, metformin’s effects are augmented when used in conjunction with lifestyle interventions (diet and exercise), leading to further weight reductions of 1.5 kg and BMI reductions of 1.08 kg/m2 when compared with metformin alone.11 The mechanism underlying metformin’s attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain is not fully understood, but preclinical studies suggest that it may prevent olanzapine-induced brown adipose tissue loss,12,13 alter Wnt signaling (an assortment of signal transduction pathways important for glucose homeostasis and metabolism),13 and influence the gut microbiome.14

Continue to: Metformin is generally...