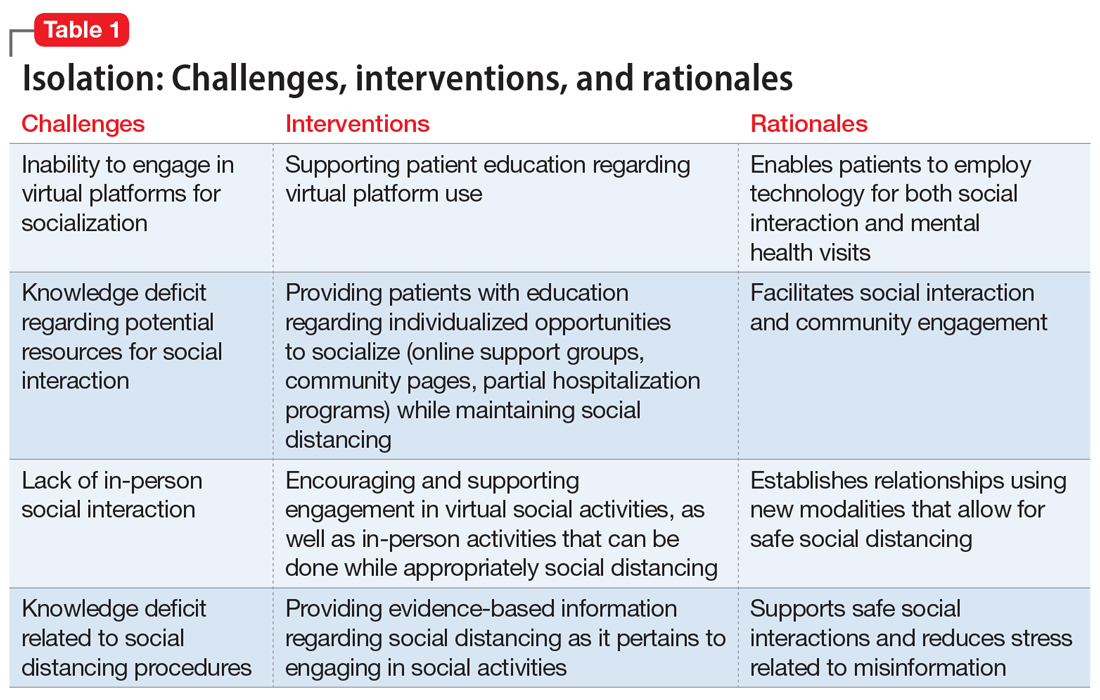

Interventions. Due to restrictions imposed to limit the spread of COVID-19, evidence-based interventions such as meeting a friend for a meal or participating in in-person support groups typically are not options, thus forcing clinicians to accommodate, adapt, and use technology to develop parallel interventions to provide the same therapeutic effects.5,6 These solutions need to be individualized to accommodate each patient’s unique social and clinical situation (Table 1). Engaging through technology can be problematic for patients with psychosis and paranoid ideation, or those with depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology or therapy visit time has to be dedicated to helping patients become comfortable and confident when using technology to access their clinicians. Patients can use this same technology to establish virtual social connections. Providing patients with accurate, factual information about infection control during clinical visits ultimately supports their mental health. Delivering clinical care during COVID-19 has required creativity and flexibility to optimize available resources and capitalize on patients’ social supports. These strategies help decrease isolation, loneliness, and exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms.

Uncertainty

Ms. L, age 42, has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea, for which she uses a continuous airway positive pressure (CPAP) device. She had been working as a part-time nanny when her employer furloughed her early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Her anxiety has gotten worse throughout the quarantine; she fears her unemployment benefits will run out and she will lose her job. Her anxiety manifests as somatic “pit-of-stomach” sensations. Her sleep has been disrupted; she reports more frequent nightmares, and her partner says that Ms. L has had apneic episodes and bruxism. The parameters of Ms. L’s CPAP device need to be adjusted, but a previously scheduled overnight polysomnography test is deemed a nonessential procedure and canceled. Ms. L has been reluctant to go to a food pantry because she is afraid of being exposed to COVID-19. In virtual sessions, Ms. L says she is uncertain if she will be able to pay her rent, buy food, or access medical care, and expresses overriding helplessness.

During COVID-19, anxiety and insomnia are driven by the sudden manifestation of uncertainty regarding being able to work, pay rent or mortgage, buy food and other provisions, or visit family and friends, including those who are hospitalized or live in nursing homes. Additional uncertainties include how long the quarantine will last, who will become ill, and when, or if, life will return to normal. Taken together, these uncertainties impart a pervasive dread to daily experience.

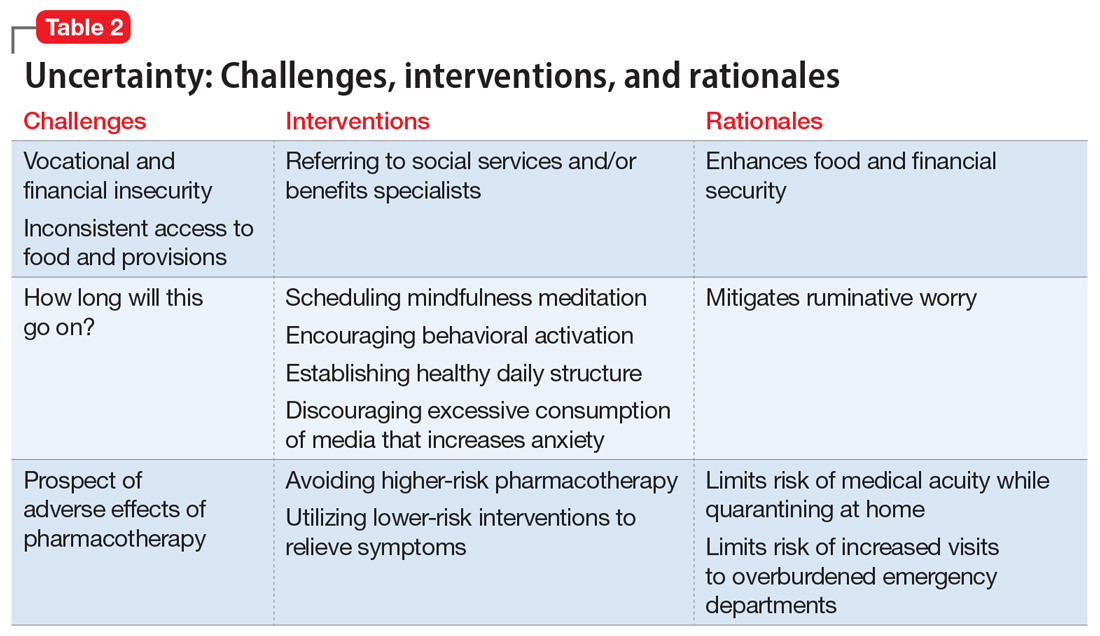

Interventions. Clinicians can facilitate access to services (eg, social services, benefits specialists) and help patients parse out what they should and can address practically, and which challenges are outside of their personal or communal control (Table 2). Patients can be encouraged to identify paralytic rumination and shift their mental focus to engage in constructive projects. They can be advised to limit their intake of media that increases their anxiety and replace it with phone calls or e-mails to family and friends. Scheduled practice of mindfulness meditation and diaphragmatic breathing can help reduce anxiety.7,8 Pharmacotherapeutic interventions should be low-risk to minimize burdening emergency departments saturated with patients who have COVID-19 and serve to reduce symptoms that interfere with behavioral activation. While the research on benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists (“Z-drugs” such as zolpidem and eszopiclone) in the setting of obstructive sleep apnea is complex, and there is some evidence that the latter may not exacerbate apnea,9 benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are associated with an array of risks, including tolerance, withdrawal, and traumatic falls, particularly in older adults.10 Sleep hygiene and cognitive-behavioral therapy are first-line therapies for insomnia.11

Household stress

Ms. M, a 45-year-old single mother with a history of generalized anxiety disorder, is suddenly thrust into homeschooling her 2 children, ages 10 and 8, while trying to remain productive at her job as a software engineer. She no longer has time for herself, and spends much of her day helping her children with schoolwork or planning activities to keep them engaged rather than arguing with each other. She feels intense pressure, heightened stress, and increased anxiety as she tries to navigate this new daily routine.

Continue to: New household dynamics...