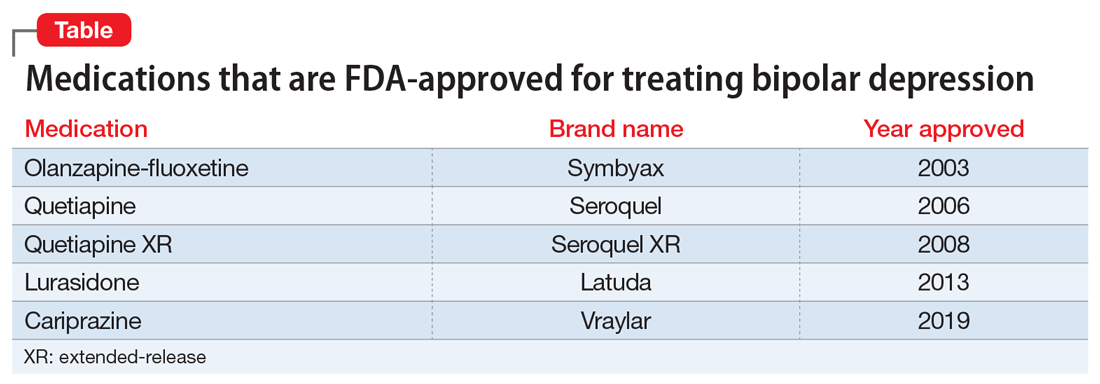

Because treatment resistance is a pervasive problem in bipolar depression, the use of neuromodulation treatments such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is increasing for patients with this disorder.1-7 Patients with bipolar disorder tend to spend the majority of the time with depressive symptoms, which underscores the importance of providing effective treatment for bipolar depression, especially given the chronicity of this disease.2,3,5 Only a few medications are FDA-approved for treating bipolar depression (Table).

In this article, we describe the case of a patient with treatment-resistant bipolar depression undergoing adjunctive TMS treatment who experienced an affective switch from depression to mania. We also discuss evidence regarding the likelihood of treatment-emergent mania for antidepressants vs TMS in bipolar depression.

CASE

Ms. W, a 60-year-old White female with a history of bipolar I disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), presented for TMS evaluation during a depressive episode. Throughout her life, she had experienced numerous manic episodes, but as she got older she noted an increasing frequency of depressive episodes. Over the course of her illness, she had completed adequate trials at therapeutic doses of many medications, including second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (aripiprazole, lurasidone, olanzapine, quetiapine), mood stabilizers (lamotrigine, lithium), and antidepressants (bupropion, venlafaxine, fluoxetine, mirtazapine, trazodone). A course of electroconvulsive therapy was not effective. Ms. W had a long-standing diagnosis of ADHD and had been treated with stimulants for >10 years, although it was unclear whether formal neuropsychological testing had been conducted to confirm this diagnosis. She had >10 suicide attempts and multiple psychiatric hospitalizations.

At her initial evaluation for TMS, Ms. W said she had depressive symptoms predominating for the past 2 years, including low mood, hopelessness, poor sleep, poor appetite, anhedonia, and suicidal ideation without a plan. At the time, she was taking clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice a day; lurasidone, 40 mg/d at bedtime; fluoxetine, 60 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg/d at bedtime; and methylphenidate, 40 mg/d, and was participating in psychotherapy consistently.

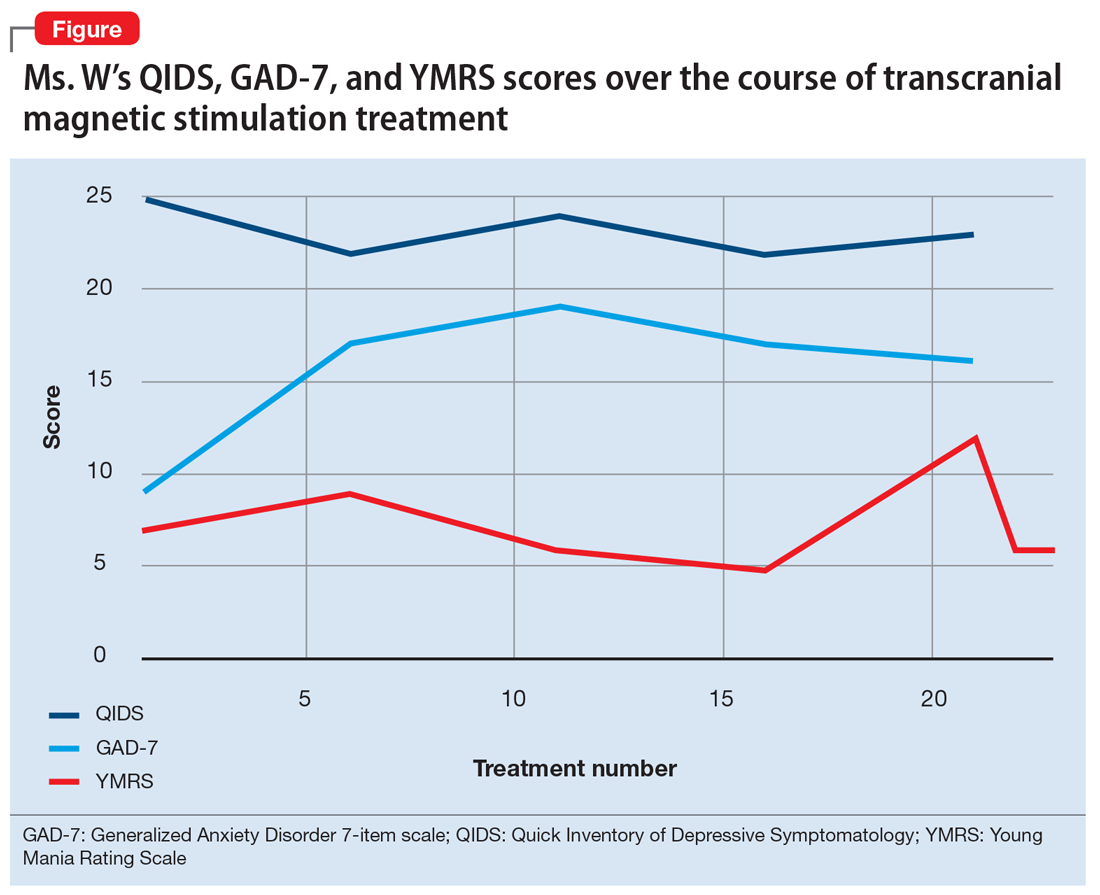

After Ms. W and her clinicians discussed alternatives, risks, benefits, and adverse effects, she consented to adjunctive TMS treatment and provided written informed consent. The treatment plan was outlined as 6 weeks of daily TMS therapy (NeuroStar; Neuronetics, Malvern, PA), 1 treatment per day, 5 days a week. Her clinical status was assessed weekly using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) for depression, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) for anxiety, and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) for mania. The Figure shows the trends in Ms. W’s QIDS, GAD-7, and YMRS scores over the course of TMS treatment.

Prior to initiating TMS, her baseline scores were QIDS: 25, GAD-7: 9, and YMRS: 7, indicating very severe depression, mild anxiety, and the absence of mania. Ms. W’s psychotropic regimen remained unchanged throughout the course of her TMS treatment. After her motor threshold was determined, her TMS treatment began at 80% of motor threshold and was titrated up to 95% at the first treatment. By the second treatment, it was titrated up to 110%. By the third treatment, it was titrated up to 120% of motor threshold, which is the percentage used for the remaining treatments.

Initially, Ms. W reported some improvement in her depression, but this improvement was short-lived, and she continued to have elevated QIDS scores throughout treatment. By treatment #21, her QIDS and GAD-7 scores remained elevated, and her YMRS score had increased to 12. Due to this increase in YMRS score, the YMRS was repeated on the next 2 treatment days (#22 and #23), and her score was 6 on both days. When Ms. W presented for treatment #25, she was disorganized, irritable, and endorsed racing thoughts and decreased sleep. She was involuntarily hospitalized for mania, and TMS was discontinued. Unfortunately, she did not complete any clinical scales on that day. Upon admission to the hospital, Ms. W reported that at approximately the time of treatment #21, she had a fluctuation in her mood that consisted of increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, and increased frivolous spending. She was treated with lithium, 300 mg twice a day. Lurasidone was increased to 80 mg/d at bedtime, and she continued clonazepam, trazodone, and methylphenidate at the previous doses. Over 14 days, Ms. W’s mania gradually resolved, and she was discharged home.

Continue to: Mixed evidence on the risk of switching