CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

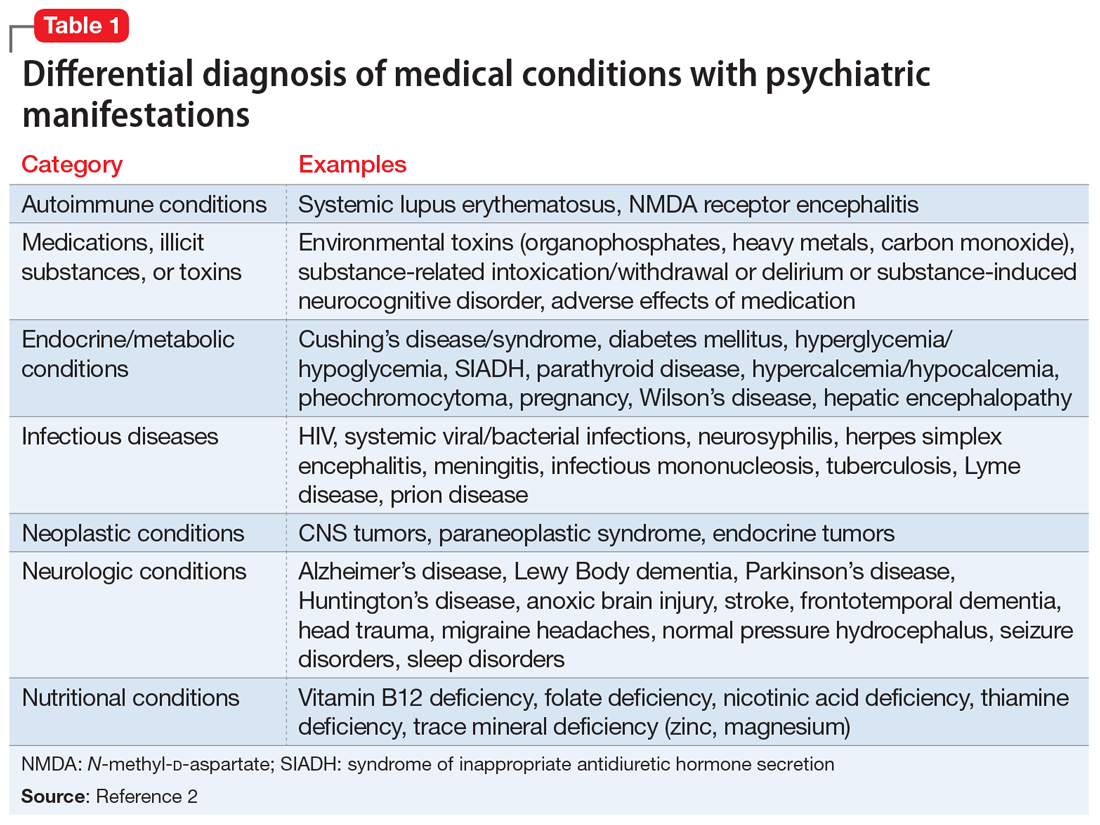

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...