Psychotic depression is difficult to recognize and treat, even for clinicians with advanced training. For example:

- only 2 of 52 psychotic depressed patients were determined to have been adequately treated before referral to a National Institute of Mental Health-supported study of ECT15

- only 3 of 46 psychotic depressed patients had been adequately treated prior to enrollment in the Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) study.9

The three most useful diagnostic criteria are spelled out in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale:

- any sign of psychosis is sufficient for designating a major depression as “psychotic”

- one well-developed sign is sufficient to prescribe treatment for psychotic depression

- well-developed vegetative signs also indicate the need to treat psychotic depression.14

ROADBLOCKS TO WIDER USE OF ECT

Many eligible patients never receive ECT, despite its track record of producing high remission rates in psychotic depression. Reasons include:

Limited access. Few psychiatrists—less than 8%—offer ECT as a treatment option, and most who do offer it practice in private hospitals.12-14

Academic low regard. Psychiatry’s academic lecturers largely ignore ECT’s efficacy in psychotic depression and therapy-resistant depression. This low regard for ECT is codified in expert algorithms, which cite ECT as an option of last resort.

Social stigma. In a recent essay summarizing medication’s weak effect in treating psychotic depression, Schatzberg states, “While ECT is a remarkably effective treatment for psychotic depression, requirements for its use are stringent, and public perception about the overall appropriateness of shock treatment is negative.”8

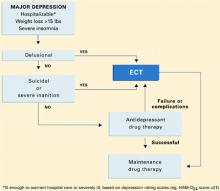

Algorithm Treatment of major depression, with or without psychotic features

ALGORITHM FOR MAJOR DEPRESSION

Because patients with psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression clearly require different treatments, differentiating between these two types is critical. Although psychotic depression can be difficult to diagnose,15,16 commonly recognized criteria are listed in the Table

Assessment. Assess each severely depressed patient for psychotic features, such as delusions and hallucinations. A useful assessment guide is the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Box).17 Also treat those with melancholia, inanition, severe weight loss and insomnia, concentration and memory difficulty, stupor, or suicidal ideation as if they had psychotic depression. These symptoms and signs are evidence that the patient’s neuroendocrine system is disturbed, an indication of severe depression that responds poorly to antidepressant drugs alone.

Treatment. Nonpsychotic depressed patients are best offered antidepressants—tricyclics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—as recommended by conventional guidelines. Insufficient response to two adequate trials calls for a careful assessment for psychosis and, if found, treatment with effective drug combinations or ECT (Algorithm).18 For patients with psychotic depression—especially those who fail medication trials or whose severe symptoms would likely respond to ECT as a primary treatment—bilateral ECT is the effective standard.19

ECT is the appropriate first option for hospitalized patients with psychotic depression—especially those who are suicidal or require supplementary feeding and sedation. It may also be considered the first option in patients who have:

- attempted suicide

- lost more than 10% of body weight (approximately 15 lbs for adults) in the weeks of their illness

- or show signs of severe melancholia, such as catatonia or pseudodementia.

TREATING NONPSYCHOTIC DEPRESSION

When medications are first-line treatment for nonpsychotic depression, how long should a trial be continued before taking another tack? How many courses should you try before you declare therapy resistance and consider ECT?

Studies of clozapine provide a useful model.20 Because of clozapine’s association with agranulocytosis and induced seizures, patients with schizophrenia usually do not receive this antipsychotic unless two 4- to 6-week trials of other neuroleptics have proven ineffective. Ethicists have deemed two failed medication trials to be sufficient before a more hazardous treatment is offered.

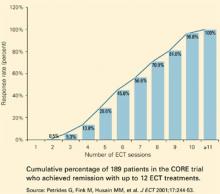

Figure Remission of major depression with ECT

We can apply a similar standard when considering ECT in patients first treated with medication.18 A patient’s depression could be defined as therapy-resistant after an inadequate response to 4-week courses (in either order) of:

- an SSRI at dosages equivalent to fluoxetine, 40 mg/d

- a tricyclic at 200 mg/d.

In depressed patients with bipolar disorder, a trial of lithium or an anticonvulsant may replace an antidepressant.

ECT is appropriate when debilitating depression persists after two adequate medication trials. Only after an adequate ECT trial has failed—and such failure is infrequent—is it reasonable to offer poorly tested augmentation and combination strategies.

What is ‘adequate’ ECT? For patients with major depression, the definition of an adequate ECT trial is complex. Although many doctors expect six ECT sessions to be sufficient, the CORE studies are finding that only 45% of patients remitted with six ECT, 81% with nine ECT, and almost all with 12 ECT sessions (Figure).9 These patients were treated with bitemporal electrode placement, the more effective form of ECT. When unilateral electrode placements are used, ECT courses may be inadequate, as this form requires special attention to electrical dosing.