SSRIs. All selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors except sertraline are associated with hyperprolactinemia and can lead to amenorrhea in some patients.12

Table 2

Differential diagnosis of secondary amenorrhea

Ovarian causes

|

Hypothalamic causes

|

Hyperprolactinemia

|

Uterine causes

|

| * Turner’s syndrome: A rare chromosomal disorder characterized by short stature, lack of sexual development at puberty. |

| † Asherman’s syndrome: Endometrial adhesions, scar tissue that develop after uterine curettage or infections. |

Anticonvulsants used as mood stabilizers to treat bipolar disorder may cause menstrual irregularities, although most data relate to women with seizure disorders.

Valproic acid has been associated with PCOS in patients with epilepsy,13 although it is unknown whether the agent’s androgenizing effects vary with age. Carbamazepine, which increases sex hormone-binding globulin, may also lead to menstrual disorders by decreasing bioavailability of circulating estrogen.14 Consider switching a patient with disrupted menses to lithium, lamotrigine, or oxcarbazepine, which have not been associated with menstrual dysfunction.

MEDICAL CAUSES

Pregnancy is the most common cause of menses cessation, followed by ovarian, hypothalamic, pituitary, or uterine dysfunction (Table 2). Hypothalamic and pituitary dysfunction often cause amenorrhea in psychiatric patients, whereas ovarian causes are common among all patients with secondary amenorrhea.15

Ovarian. In PCOS, the ovaries and sometimes the adrenal glands produce excess androgens, leading to infrequent or light periods (oligomenorrhea) or amenorrhea.

Patients with depression are prone to ovarian failure in their 30s or 40s, possibly because of chronic HPA disruption.4 Premature ovarian failure also is common among patients with Turner’s syndrome, a rare chromosomal disorder characterized by short stature and lack of sexual development at puberty. Ovarian failure also can occur spontaneously.

Hypothalamic. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea occurs in mood and eating disorders. Emotional stress, excessive physical exercise, and nutritional deficiencies reduce LHRH secretion by the hypothalamus, which interrupts the reproductive cycle. Cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cancer, and other acute and chronic medical illnesses can cause significant physiologic stress, thus leading to HPA dysfunction. Hypothalamic amenorrhea is treated by targeting the underlying psychiatric or medical condition.

Pituitary. Prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors, such as a pituitary adenoma, must be ruled out in patients whose prolactin levels remain high after a medication change.15 Hypothyroidism also can trigger hyperprolactinemia by causing pituitary gland hyperplasia.

Uterine. Women who have had uterine curettage or infections can develop adhesions and scar tissue that ablate the endometrial lining. This condition, called Asherman’s syndrome, is the most common uterine cause of menstrual disruption.

EVALUATING SECONDARY AMENORRHEA

When a patient presents with secondary amenorrhea, immediately rule out pregnancy because psychiatric disorders often are managed differently in pregnant than in nonpregnant women.16

Next, take a thorough patient history to determine whether referral is necessary. Ask about weight loss (intentional or unintentional), increased stressors, or a medical illness that may point to functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Galactorrhea or vision changes—particularly loss of peripheral vision—could suggest a pituitary tumor. Skin changes, cold intolerance, fatigue, or constipation could indicate hypothyroidism.

Menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness could point to premature ovarian failure. Galactorrhea may indicate high prolactin levels. Obesity, hirsutism, or acne could point to PCOS. Consider Asherman’s syndrome in patients with endometritis or who have had a uterine dilation and curettage.

Laboratory testing. Once pregnancy is ruled out, measure prolactin. If it exceeds 25 ng/mL by 15 ng/mL or more, do a confirmative second prolactin test. If a patient is taking a prolactin-raising medication and her prolactin was not gauged before treatment, change to a prolactin-sparing agent, then measure her prolactin 2 weeks later.17

When to refer. If prolactin persistently exceeds 50 ng/mL even after changing medications, refer the patient for brain MRI to rule out a pituitary tumor.

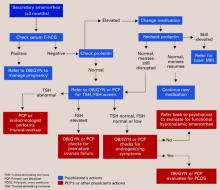

Tests for other underlying medical causes of secondary amenorrhea—and when to perform them—are shown in the algorithm. Psychiatrists can give these tests or refer the patient to her primary care physician.

Algorithm Laboratory evaluation of secondary amenorrhea

Communication between care team members is key to determining treatment. If a medical problem arises during psychiatric treatment, call the patient’s primary care physician or send a letter describing the problem. Also send the referring physician available lab reports.

CASE CONTINUED: TREATMENT CHANGE

Ms. J’s psychiatrist tapered risperidone to 1 mg/d for 2 weeks, then switched to olanzapine, 5 mg/d. Three weeks later, her prolactin decreased to 25 ng/mL. She continued fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and tolerated the change in antipsychotics.

Ms. J’s bipolar disorder remains well-controlled, but menses had not resumed for another 2 months, so the psychiatrist referred Ms. J back to her primary care physician. Androgenizing and pituitary tumors were ruled out based on normal TSH, prolactin, and testosterone levels. Ms. J was diagnosed as having PCOS based on her constellation of signs and symptoms. She was started on metformin, an insulin sensitizer used to treat PCOS, and was referred to a dietitian to help her lose weight.