Consultation/liaison (C/L) psychiatrists assess capacity in 1 of 6 consults,1 and these evaluations must be quick but systematic. Hospital time is precious, and asking for a psychiatry consult inevitably slows down the medical team’s efforts to care for sick or injured patients.

We suggest an approach our C/L service developed to rapidly weigh capacity’s three dimensions—risks, benefits, and patient decisions—to formulate appropriate opinions for the medical team.

A standard for capacity

In most cases, capacity must be assessed and considered adequate before a patient can provide informed consent for a medical intervention. Because a patient might be capable of making some decisions but not others, the standard for determining capacity is not black and white but a sliding scale that depends on the magnitude of the decision being made.

As physicians, psychiatrists understand doctors’ frustrations when they believe a patient is making the wrong treatment choice. When the primary team turns to us, they want us to help determine the most appropriate course of action.

Capacity is determined by weighing whether the patient is competent to exercise his or her autonomy in making a decision about medical treatment. We do not assess global capacity; the goal is to provide an unbiased opinion about specific capacity for a given situation–“Does Mr. X have the ability to accept/refuse this treatment option presented to him?”

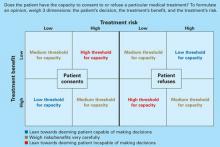

Capacity’s three dimensions. The means to achieve this goal are often complex. Roth et al2 proposed that capacity could be measured on a sliding scale. Wise and Rundell3 agreed and developed a two-dimension table to show that capacity can be evaluated at different thresholds, depending on the patient’s clinical situation. We expanded this model (Figure) to include three dimensions to consider when you evaluate capacity:

- risk of the proposed treatment (high vs. low)

- benefit of the treatment (high vs. low)

- the patient’s decision about the treatment (accept vs. refuse).

If a treatment’s benefits far outweigh the risks and the patient accepts that treatment, he is probably capable of making that decision and a lenient (low) threshold to establish capacity applies. If the same patient refuses the high-benefit, low-risk treatment, then he might be incapable of making that decision and a stringent (high) threshold to establish capacity comes into play. Our C/L service often uses this model when discussing capacity evaluations with the primary team. It explains why some capacity evaluations—when a patient agrees to a low-risk, high-benefit procedure—might take minutes, whereas others—those that fall into the medium threshold for capacity—take hours. Consider the following cases.

Figure 3-dimension model for evaluating capacity

Three cases: Is capacity evaluation needed?

Mr. X, age 25, was in a motor vehicle accident that caused trauma to his esophagus. He requires a feeding tube because he will be unable to eat for several weeks. The risk of the procedure (feeding tube placement) is low, and the benefit (getting possibly life-saving nutrition) is high.

If Mr. X refuses the feeding tube, he may be incapable of making this decision and would require a rigorous capacity evaluation (high-threshold capacity). If he consents, he is making a choice with which most reasonable people would agree, and establishing capacity would be less important (low-threshold capacity).

Mr. J, age 95, has congestive heart failure, diabetes, and liver disease. If he consents to a liver transplant—a treatment likely to be low-benefit and high-risk—he would require a rigorous capacity evaluation. If he refuses this surgical intervention, then more-lenient capacity criteria would apply.

Mrs. F, age 59, has breast cancer with metastases. Her oncologist is recommending bilateral mastectomy, radiation, chemotherapy, and an experimental treatment that has shown favorable results. The risk of treatment is high, and the benefit is unknown but most likely high. Since this is a high-risk, high-benefit intervention, the capacity threshold is medium. Whether she consents to or refuses treatment, you must weigh risks and benefits very carefully with her.

The primary team’s role

A common myth holds that only psychiatrists can determine capacity, but any physician can.4 The primary team may feel comfortable deciding a patient’s capacity without seeking consultation after asking the screening questions in Table 1.5,6 A patient who gives consistent and appropriate answers to these screening questions usually also can answer the more detailed questions psychiatrists would ask and thus has sufficient capacity.

When uncertainties remain after screening, we recommend that the primary team ask psychiatry for an opinion. Knowing what the primary team is thinking about a difficult case often helps the psychiatric consultant. So when consulting with psychiatry, we suggest that the primary team: