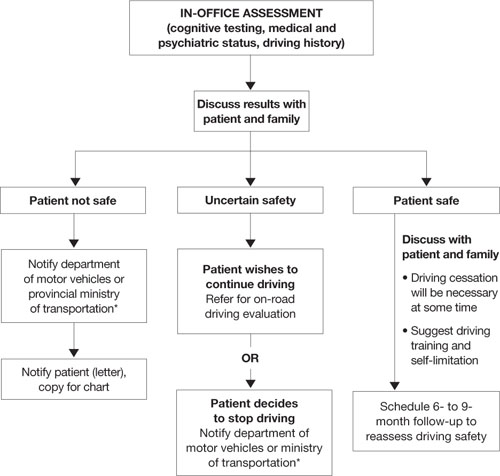

Algorithm: 3 options for drivers with dementia, based on in-office assessment

* Observe legislation or statutes that address reporting unsafe drivers to the department of motor vehicles or ministry of transportation

On-road driving tests

Because some individuals with mild dementia can drive safely for extended periods, international recommendations for assessing the driver with dementia emphasize on-road driving tests.10,13,20–22 American10 and Canadian guidelines13 suggest that a dementia diagnosis is not sufficient to withdraw licensure.

A formal driving assessment is necessary to establish road safety for patients with mild dementia except when the need for license withdrawal is evident, such as when the patient has:

- a history of major driving problems (such as crashes or driving the wrong way on a highway)

- significant contraindications to driving on the history or physical examination (such as severe inattention or psychosis).

Challenges of on-road testing. On-road tests may be the gold standard, but they are not without clinical problems.

Need to retest. Because almost all dementias are progressive and driving skills deteriorate over time, most guidelines recommend periodic retesting. For patients with dementia who pass on-road evaluations, limited evidence supports retesting every 6 months.14 Take an individual approach, however, because of the various rates at which the dementias progress.

Testing vs real world conditions. Structured on-road testing is not equivalent to unstructured real-world driving, in which the patient often must navigate without instruction or assistance.

Rural vs urban driving. Road tests conducted in urban areas assess skills associated with complex conditions and the need to respond quickly to crises. They might not assess as well rural driving, which requires sustained attention on monotonous roads.

Inaccessibility. Cost and lack of availability of on-road tests, particularly in rural areas, limit the number of patients whose performance can be evaluated.

CASE CONTINUED: Distressing results

Mr. D has a history of decline in cognition and function, objective cognitive difficulties, and a subtle history of driving problems. You refer him for a specialized on-road test, and the report indicates that he failed. Errors included wide turns, driving too slowly, getting caught in an intersection twice during red lights while attempting to turn left, driving on the shoulder, and failing to signal lane changes. You review the results with Mr. D and his wife and recommend that he cease driving immediately.

Mr. D is furious, and his wife is dismayed. He demands to know how he can continue to play golf, which is his only form of exercise and recreation. Will she have to give up her bridge club? How will they shop for food? They request permission to at least to drive to the grocery store during the daytime.

You explain that no system allows individuals to drive only at certain times, and for the sake of safety you cannot grant them special permission. You discuss alternatives, such as asking their daughter for assistance with grocery shopping and taking taxis or ride-sharing with friends who play golf and bridge.

Remain firm, but ease the blow

Driving cessation orders distress patients, families, and clinicians. A failed road test clearly indicates unsafe driving, and driving cessation is critical to public safety.

A review by Man-Son-Hing et al23 found that drivers with dementia performed worse than nondemented controls in all studies that examined driving performance (on-road, simulator, or caregiver report). Simulators showed problems such as off-road driving, deviation from posted speed, and more time to negotiate left turns.24

By comparison, only 1 of 3 studies using state crash records showed an increased risk of collisions in persons with dementia compared with controls.23 From a research perspective, however, studies that use state-reported collisions to assess driving risk are confounded by driving restrictions on persons with dementia.

Mr. D wants to continue driving with restrictions. No studies have shown reduced crash rates when drivers with dementia used compensatory strategies such as restrictions, retraining/education, having a passenger “co-pilot,” on-board navigation, or cognitive enhancers.23

If Mr. D had passed the road test, the situation would have been more ambiguous. Two studies have examined on-road driving performance over time in patients with early-stage dementia.25,26 Both studies followed drivers prospectively for 2 years, and those with mild dementia (vs very mild or no dementia) were most likely to show a decline in driving skills: