Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/08/depression-in-older-adults.html#comments

Depression in older adults (age ≥65) can devastate their quality of life and increase the likelihood of institutionalization because of behavioral problems.1 Depression is a primary risk factor for suicide, and suicide rates are highest among those age ≥65, especially among white males.2 The burden of geriatric depression can extend to caregivers.1 Prompt recognition and treatment of depression could help minimize morbidity and reduce suffering in older adults and their caregivers.

Although geriatric depression varies in severity and presentation, common categories include:

- major depressive disorder (MDD)

- vascular depression

- dysthymia

- depression in the context of dementias, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and executive dysfunction.

Diagnoses in this population generally correspond with DSM-IV-TR criteria, but geriatric depression has distinct clinical manifestations.1,2 Compared with younger depressed patients, older adults are less likely to endorse depressed mood and more likely to report a lack of emotions.1,2 Older patients report feelings of irritability and fearfulness more often than sadness.1,2 Mood symptoms tend to be transient, reoccur frequently, and display either a diurnal pattern or multiple fluctuations in a single day.1,2 Other common presentations include loss of interest in usual activities, lack of motivation, social withdrawal, and decline in activities of daily living.1,2

Summary of recommendations

Age-specific recommendations for assessing and treating geriatric depression can be generated in part from evidence-based reviews, meta-analyses,3 and geriatric expert consensus guidelines.4 Such guidelines and recommendations often do not take into account the marked heterogeneity of medical, cognitive, and overall functioning in patients age ≥65, however, because they are based on studies of younger populations and patients with complicated issues often are excluded from studies. The recommendations in this article are based largely on findings from a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored project by Alexopoulos et al to develop consensus guidelines for managing geriatric depression and expert opinion from clinicians who treat geriatric patients.4

During your initial clinical evaluation, confirm the diagnosis and type, duration, and severity of depression. Seek to understand the biopsychosocial context of each patient’s presentation. Carefully consider your patient’s suicide risk. Hospitalization may be required if he or she is at high risk for suicide or has complex medical and social circumstances that cannot be managed adequately in an outpatient setting.5

Unipolar major depression

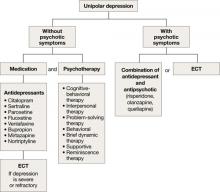

For unipolar, nonpsychotic geriatric depression, the NIH-Alexopoulos et al guidelines emphasize a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy (Algorithm 1).4 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and venlafaxine are first-line options.4,6,7 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), bupropion, and mirtazapine are alternatives.4 Among SSRIs, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline are preferred initial antidepressants. Fluoxetine is used less frequently.4 Paroxetine also is less commonly used because of its anticholinergic effects and because the drug inhibits cytochrome P4502D6,2 which metabolizes several medications commonly prescribed for older adults. Among TCAs, nortriptyline is preferred.4 Studies have shown that duloxetine improves depression and is safe and well-tolerated in older adults with recurrent MDD.8 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an option for treating severe or treatment-resistant unipolar major depression.9

For unipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, guidelines recommend a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic or ECT.4 Atypical antipsychotics are preferred over typical antipsychotics4; risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are most frequently used.4 Clinical data on aripiprazole and ziprasidone in older adults are limited. Many geriatric experts recommend continuing an antipsychotic for 6 months after symptom remission, then gradually tapering the dose.4

During acute illness, administer an anti-depressant for 6 to 12 weeks at the individually determined dose required to achieve symptom remission.6 For an older adult experiencing a first lifetime episode of major depression, continue antidepressant treatment for 1 year after remission.4 If your patient has had 2 lifetime episodes of major depression, continue the antidepressant at the same dose used to achieve remission for at least 3 years. For patients who have had ≥3 episodes of depression or whose index episode was particularly severe or involved significant suicidal thoughts or behaviors, continue maintenance treatment indefinitely.

Algorithm 1: Treatment for unipolar depression in geriatric patients

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy

Bipolar depression

Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate—as monotherapy or in combination with an antidepressant—are recommended to treat bipolar depression without psychotic symptoms in older adults (Algorithm 2).10 For bipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, a combination of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic or ECT is recommended.10

Older adults’ increased sensitivity to side effects and reduced ability to tolerate lithium may limit its use and may prompt you to consider atypical antipsychotics as alternatives to other mood stabilizers. Although quetiapine and fluoxetineolanzapine combination are well studied in younger patients,11,12 there is a lack of data to support their clinical effectiveness and tolerability in older adults. Among antidepressants, SSRIs or bupropion are preferred over TCAs to prevent a switch to mania.10 Lamotrigine is an effective maintenance treatment for bipolar depressive episodes in older adults.13