A review of pharmacotherapy for aggression in children found the largest effects for methylphenidate for aggression in ADHD (mean effect size=0.9, combined N=844).13 Our clinical experience has been that pediatric patients with ADHD or ODD with ADHD often have high levels of reactive aggression that presents as mood swings, and aggressively treating ADHD often results in improved mood and other ADHD symptoms.

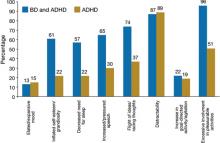

Figure 2 Symptoms that differentiate BD from BD with comorbid ADHD

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder

Source: Reference 11

Anxiety disorders

The estimated prevalence of child and adolescent anxiety disorders is 10% to 20%14; in our sample the prevalence was 15%. These disorders include GAD, separation anxiety disorder, social phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Often, children with GAD worry excessively and become upset during transitions when things don’t proceed as they expect, with resultant angry outbursts and mood swings. Mood swings and difficulty sleeping are common in children with anxiety disorders or BD. Anxiety disorders often will be missed unless specific triggers of the mood swings or angry outbursts—as well as differentiating symptoms such as excessive fear, worry, and psychosomatic symptoms—are assessed.

In our clinical experience, simply asking a child if he or she is anxious is not sufficient to uncover an anxiety disorder. Although the CPRS-L:R will screen for anxiety disorders, we have found that the Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) developed by Birmaher et al15 is more specific. This tool can be used in patients age ≥8. The parent and child versions of the SCARED contain 41 items that measure 5 factors:

- general anxiety

- separation anxiety

- social phobia

- school phobia

- physical symptoms of anxiety.

The SCARED takes 5 minutes to fill out and is available in parent and child versions.

Secondary mood disorders

Many patients in our sample had a mood disorder secondary to the neurologic effects of alcohol on the developing brain. For more about maternal alcohol use, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, and mood swings, visit this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

What BD looks like in children

In our sample, 12% of patients referred for mood swings were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder (BDI), bipolar II disorder (BDII), or bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified (BD-NOS). In the United States, lifetime prevalence of BDI and BDII in adolescents age 13 to 17 is 2.9%.16 No large epidemiologic studies have looked at the lifetime prevalence of BD in children age <13.

How often a clinician sees BD in children and adolescents largely depends on the type of setting in which he or she practices. Although in the general population BD is relatively rare compared with other childhood psychiatric disorders, on child/adolescent inpatient units it is common to find that 30% to 40% of patients have BD.17

The best longitudinal study to date of the phenomenology, comorbidity, and outcome of BD in children and adolescents is the National Institute of Mental Health-funded Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study (COBY).18 In this ongoing, longitudinal study, 413 youths (age 7 to 17) with BDI (N=244), BDII (N=28), or BD-NOS (N=141) were rigorously diagnosed using state-of-the-art measures, including the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present version19 and re-evaluated every 9.4 months for 4 years. When organizing this study, investigators found that DSM-IV criteria for BD-NOS were too vague to be useful and developed their own criteria (Table 2).18

For BDI patients in the COBY study, the mean age of onset for bipolar symptoms was 9.0±4.1 years and the mean duration of illness was 4.4±3.1 years. Researchers reported that at the 4-year assessment approximately 70% of patients with BD recovered from their index episode, and 50% had at least 1 syndromal recurrence, particularly depressive episodes.20 Analyses of these patients’ weekly mood symptoms showed that they had syndromal or subsyndromal symptoms with numerous changes in symptoms and shifts of mood polarity 60% of the time, and psychosis 3% of the time. During this study, 20% of BDII patients progressed to BDI, and 25% of BD-NOS patients converted to BDI or BDII.

Further analysis of the COBY data revealed that onset of mood symptoms preceded onset of clear bipolar episodes by an average of 1.0±1.7 years. Depression was the most common initial and most frequent episode for adolescents; mood lability was seen more often in childhood-onset and adolescents with early-onset BD. Depressed children had more severe irritability than depressed adolescents, and older age was associated with more severe and typical mood symptomatology.21