By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy

The ATRQ examines the efficacy (improvement from 0% [not improved at all] to 100% [completely improved]), and adequacy (adequate duration and dose) of any antidepressant treatment in a step-by-step procedure.1,8,9 For a copy of the ATRQ, click here.

While conducting the interview, clinicians ask about treatment adherence to each medication trial. A treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, from monotherapy to combination to augmentation.10 For each trial, the ATRQ systematically reviews 4 strategies to enhance treatment response:

- increasing the initial antidepressant dosage11

- combining the initial antidepressant with another antidepressant, typically from another class12

- augmenting the initial antidepressant with a nonantidepressant12

- switching from the initial antidepressant to another antidepressant.13

These strategies also are applied in cases of lost sustained antidepressant efficacy or depressive relapse/recurrence, although empirical evidence supporting these strategies is lacking, with the possible exception of dose increase.14,15

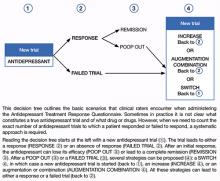

In the convention our group adopted, an adequate antidepressant trial must be ≥6 weeks in total length, with a dose within an adequate range as specified in the medication’s package insert. In addition, for the purposes of conducting TRD trials, we have considered a patient treatment-resistant if response to adequate dose and duration is <50%. On the ATRQ, 50% improvement refers to 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission. In an initial clinical trial that lasts ≥6 weeks, any dose increase (for ≥4 weeks) represents optimization and is not considered a new or separate trial, whereas augmentation or combination therapy (for ≥3 weeks) or a switch to another antidepressant (for ≥6 weeks) are considered new trials/treatments.

Decision tree for ATRQ. Because antidepressant treatment always is constrained by personal (eg, adherence, insurance coverage, etc.) and clinical (eg, contraindications due to comorbid conditions, side effects, etc.) considerations, we propose a decision tree to help clinicians determine the number of failed antidepressant trials their patient experienced (Figure). Although this tree does not represent all treatment scenarios, we hope it could help clinicians implement TRD treatment strategies because it highlights proper assessment of treatment duration, dosage, and changes before applying a TRD diagnosis.

The ATRQ meticulously examines patients’ antidepressant history to identify:

- pseudo-resistance, to guide adequate dosing and/or duration, and

- resistance, to propose next-step treatment.

Pseudo-resistance refers to treatment failures that can be attributed to factors such as inadequate treatment dosing or duration, atypical pharmacokinetics that reduce agents’ effectiveness, patient nonadherence (eg, due to adverse effects), or misdiagnosis of the primary disorder (ie, other mood disorders or depressive subsets such as dysthymia or minor depression mistreated as unipolar depression).16,17 Studies show that many patients with MDD referred to specialty settings are undertreated and receive inadequate antidepressant doses,18 which suggests that many referrals for TRD are in fact pseudo-resistance.19 Despite the lack of consensus on criteria for TRD,1 standardization of what constitutes treatment adequacy during antidepressant trials (eg, adherence, dose, duration) is indispensable.

Clinical application of the ATRQ. Because TRD may require specific interventions, we first need to properly identify treatment resistance. Also, systematic use of a classification system enhances the ability of clinicians and patients to provide meaningful descriptions of antidepressant resistance.

In clinical practice, choice of treatment strategy is based on factors that include partial or nonresponse, tolerability, avoiding withdrawal symptoms, the need to target side effects of a current antidepressant by administering another drug, cost, avoiding drug-drug interactions, and patient preference. Because a treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, it is essential to obtain information about all treatments to determine the number of failed clinical trials a patient may have had for the current MDD episode and lifetime episodes. The importance of asking about adherence to each trial cannot be overemphasized.

Figure: Using the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire: A decision tree