Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Off-label prescribing (OLP)—prescribing a medication in a manner different from that approved by the FDA—is common and can be clinically beneficial. A survey of 200 British psychiatrists found that 65% had prescribed a medication off-label within the previous month.1 However, OLP often is not supported by strong evidence and carries clinical risks, such as adverse effects and unproven efficacy. A 2006 study found that only 4% of off-label prescriptions of psychiatric medications were supported by strong scientific evidence.2

OLP may become unavoidable for several reasons, including:

- lack of data from quality trials on a specific indication or patient population

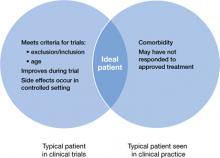

- patients seen in clinical practice vary from those evaluated in clinical trials (Figure 1)

- the need to treat patients who do not respond to first-line therapies or have treatment-resistant conditions.

At times, OLP may be a psychiatrist’s only option: >80% of DSM-IV-TR diagnoses have no FDA-approved medication.3

No practice guidelines are available to help clinicians decide when OLP is appropriate. Psychiatrists must rely on multiple, sometimes-conflicting sources to determine whether evidence is sufficient to support off-label use in a specific clinical scenario. This article looks at types of OLP and offers suggestions for clinicians who are considering prescribing a medication outside of its approved use.

Figure 1: Clinical trial patients vs ‘real world’ patients

The FDA’s role

Once the FDA approves a medication for a specific indication, physicians legally are permitted to prescribe that drug for indications, patient populations, or dosages not included on the FDA-approved label.2,4 The FDA oversees and regulates pharmaceutical companies, not physicians.4 Currently, pharmaceutical companies cannot market a drug for an indication not included on the label, but physicians are free to use the drug for any condition or disease.5

When is OLP used?

According to Baldwin et al,6 prescribing that is considered off-label generally falls into 1 of the following 4 categories:

Indication. This type of OLP is prescribing a medication for an indication other than those included on the FDA-approved label. The off-label indication may be a logical extension of an approved indication. For example, a medication approved for treating erectile dysfunction might be prescribed to a patient who is experiencing antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.

If a pharmaceutical company wishes to expand the indications of a medication they must seek supplemental approval from the FDA. This is a long, expensive process. In certain situations, it may be in the patient’s best interest to prescribe a medication off-label until that indication becomes approved. When clinicians identify new uses for existing medications while they care for patients, it is considered field discovery, and this innovative process may occur years before such indications receive FDA approval.

Dosage. The most common example of this type of OLP in psychiatry is prescribing higher-than-approved dosages of antidepressants or antipsychotics for patients who do not respond to the maximum approved dosages. The effectiveness of this strategy is unknown.6

Duration. This typically entails prescribing a medication for a period of time longer than specified on the label. For example, many antidepressants are approved only for treating depressive illness. Therefore, continuing an antidepressant as maintenance therapy for a patient who is in remission could be considered off-label. Benzodiazepines are approved primarily for short-term management of anxiety, but commonly are prescribed for patients with chronic, disabling anxiety disorders who do not respond to other medications.6

Patient age. The FDA approves medications for use in patients within a specified age range based on patients evaluated in clinical trials, and most trials of psychotropics include patients age 18 to 65. However, it is highly unlikely that a 17-year-old patient’s drug metabolism changes substantially when he or she reaches age 18, or when a 65-year-old turns 66. Research has demonstrated that medications can be effective outside of strict age ranges. For example, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that antidepressants are efficacious in treating depression in geriatric patients, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are efficacious in treating obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in children and adolescents.6

Few medications have been approved for treating geriatric patients with psychiatric illness. For example, no drugs are approved for treating psychotic, behavioral, and mood symptoms that may accompany dementia. For this reason, clinicians often prescribe psychotropics off-label to these patients.

The rate of psychotropic prescriptions to children and adolescents—particularly antidepressants and antipsychotics—has been increasing.7-9 The British Association for Psychopharmacology suggested that it may be reasonable to apply what we know regarding adults’ responses to drug treatment to children and adolescents with schizophrenia or OCD, but more caution is required in young patients with mood or anxiety disorders.10