Acute psychosis is a symptom that can be caused by many psychiatric and medical conditions. Psychotic patients might be unable to provide a history or participate in treatment if they are agitated, hostile, or violent. An appropriate workup may reveal the etiology of the psychosis; secondary causes, such as medical illness and substance use, are prevalent in the emergency room (ER) setting. If the patient has an underlying primary psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia or mania, illness-specific intervention will help acutely and long-term. With agitated and uncooperative psychotic patients, clinicians often have to intervene quickly to ensure the safety of the patient and those nearby.

This article focuses on the initial evaluation and treatment of psychotic patients in the ER, either by a psychiatric emergency service or a psychiatric consultant. This process can be broken down into:

- triage or initial clinical assessment

- initial psychiatric stabilization, including pharmacologic interventions and agitation management

- diagnostic workup to evaluate medical and psychiatric conditions

- further psychiatric evaluation

- determining safe disposition.1

Triage determines the next step

Initial clinical assessment and triage are necessary to select the appropriate immediate intervention. When a patient arrives in the ER, determine if he or she requires urgent medical attention. Basic initial screening should include:

- vital signs

- finger stick blood glucose

- medical history

- signs or symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal

- signs of trauma (eg, neck ligature marks, gunshot wounds, lacerations)

- asking the patient to give a brief history leading up to the current presentation.

A review of medical records may reveal patients’ medical and psychiatric history and allergies. Collateral documentation—such as ambulance run sheets or police reports—may provide additional information. If no immediate medical intervention is warranted, determine if the patient can wait in an open, unlocked waiting area or if he or she needs to be in an unlocked area with a sitter, a locked open area, or a secluded room with access to restraints. In general, psychotic patients who pose a threat of harm to themselves or others or cannot care for themselves because of their psychosis need locked areas or observation.

Initial psychiatric stabilization

Agitation is diagnostically unspecific but can occur in patients with psychosis. Psychotic patients can become unpredictably and impulsively aggressive and assaultive. Rapid intervention is necessary to minimize risk of bodily harm to the patient and those around the patient. Physicians often must make quick interventions based on limited clinical information. It is important to recognize early signs and symptoms of agitation, including:

- restlessness (pacing, fidgeting, hand wringing, fist clenching, posturing)

- irritability

- decreased attention

- inappropriate or hostile behaviors.2

Pharmacologic interventions. The initial goals of pharmacologic treatment are to calm the patient without oversedation, thereby allowing the patient to take part in his or her care and begin treatment for the primary psychotic illness.3,4 Offering oral medications first and a choice of medications may help a patient feel more in control of the situation. If a patient has to be physically restrained, pharmacotherapy may limit the amount of time spent in restraints.

Medication choice depends on several factors, including onset of action, available formulation (eg, IM, liquid, rapidly dissolving), the patient’s previous medication response, side effect profile, allergies or adverse reactions to medications, and medical comorbidities.3 If a patient has a known psychotic illness, it may be helpful to administer the patient’s regular antipsychotic or anxiolytic medication. Some medications, such as lithium, are not effective in the acute setting and should be avoided. Additionally, benzodiazepines other than lorazepam or midazolam should not be administered IM because of erratic absorption.

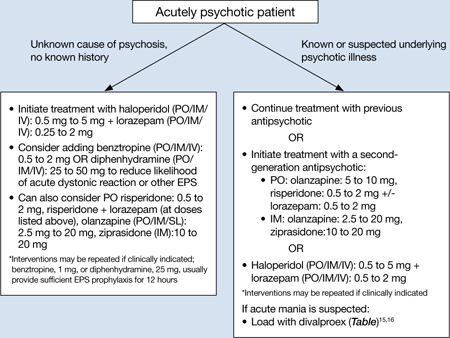

Antipsychotics can be used for psychotic patients with or without agitation. Benzodiazepines may treat agitation, but are not specific for psychosis. Haloperidol can be used to treat acute psychosis and has proven efficacy for agitation. Benzodiazepines can decrease acute agitation and have efficacy similar to haloperidol, but with more sedation.5 A combination of lorazepam and haloperidol is thought to be superior to either medication alone.6 Lorazepam helps maintain sedation and decreases potential side effects caused by haloperidol. Consensus guidelines from 2001 and 2005 recommend combined haloperidol and lorazepam for first-line treatment of acute agitation.3,7 High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol have an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), particularly acute dystonic reactions—involuntary, sustained muscle contractions—in susceptible patients (eg, antipsychotic-naïve patients); consider starting diphenhydramine, 25 to 50 mg, or benztropine, 0.5 to 2 mg, to prevent EPS from high-potency antipsychotics (Algorithm 1).

Algorithm 1: Treating acute psychosis: Choosing pharmacologic agents

EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms; PO: by mouth; SL: sublingual

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) increasingly have been used for managing acute agitation in patients with an underlying psychotic disorder. Guidelines from a 2012 American Association for Emergency Psychiatry workgroup recommend using an SGA as monotherapy or in combination with another medication instead of haloperidol to treat agitated patients with a known psychotic disorder.8 Clinical policy guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians recommend antipsychotic monotherapy for agitation and initial treatment in patients with a known psychiatric illness for which antipsychotic treatment is indicated (eg, schizophrenia).9 For patients with known psychotic illness, expert opinion recommends oral risperidone or olanzapine.3,8 The combination of oral risperidone plus lorazepam may be as effective as the IM haloperidol and IM lorazepam combination.10 Patients who are too agitated to take oral doses may require parenteral medications. Ziprasidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole are available in IM formulations. Ziprasidone, 20 mg IM, is well tolerated and has been shown to be effective in decreasing acute agitation symptoms in patients with psychotic disorders.11 Olanzapine is as effective as haloperidol in decreasing agitation in patients with schizophrenia, with lower rates of EPS.12 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder decreased within 2 hours of IM olanzapine administration.13 Both IM ziprasidone and olanzapine have a relatively rapid onset of action (within 30 minutes), which makes them reasonable choices in the acute setting. Olanzapine has a long half-life (21 to 50 hours); therefore, patients’ comorbid medical conditions, such as cardiac abnormalities or hypotension, must be considered. If parenteral medication is required, IM olanzapine or IM ziprasidone is recommended.8 IM haloperidol with a benzodiazepine also can be considered.3