The authors’ observations

Psychotic symptoms occurring during long-distance trips have been well described in psychiatric literature. Westbound travel could exacerbate depression. Emerging mania has been documented in eastbound flights, which could be related to sleep deprivation.12,13 The incidence of psychotic exacerbations is correlated with the number of time zones crossed.12

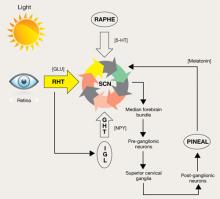

A change in environment, unfamiliar surroundings, presence of strangers, physical inactivity, and a sense of isolation all contribute to jet lag syndrome. Long-distance air travel also disrupts zeitgebers, environmental cues that induce adjustments in the internal body clock.12,14 The body clock is controlled mainly by the SCN in the hypothalamus, which is primarily regulated by the light/dark cycle via melatonin secretion (Figure).

Endogenous changes in circadian rhythms and melatonin secretion abnormalities are present in the pathophysiological mechanism of several psychiatric disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Trbovic hypothesized that in essence schizophrenia could be a sleep disorder and SCN dysfunction may contribute to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.15 Several research findings support this hypothesis (Table 2). Recent evidence suggests that abnormal circadian melatonin metabolism may be directly related to the schizophrenia pathophysiology.16 Because melatonin production is regulated by the SCN and jet lag resets the melatonin cycle, a defective SCN may not respond well to such adjustments.

Mr. F’s symptomatology is illustrative of the jet lag scenario. His auditory hallucinations became “more supportive” and helpful during his eastbound flight, whereas after his return to the United States, depression was the predominant mood symptom. Psychotic exacerbation also was noticeable after his return.

There are no recommended treatments for psychosis related to jet lag. Antipsychotics often are used, although there is no accepted agent of choice. Treatment of jet lag includes addressing sleep loss and desynchronization.17 Medications suggested for treatment of sleep loss are antihistamines (H1 receptor antagonists), benzodiazepines, and imidazopyridines (zolpidem, zopiclone). Light therapy or administration of melatonin, ramelteon, or agomelatine can help jet-lagged patients resynchronize with the environment.

Figure: Pathways for light: Circadian timing system

Photic information reaches the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) through the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), which uses glutamate (GLU) as a neurotransmitter. A multisynaptic indirect pathway also carries photic information to the SCN. This indirect route arises from the RHT, projects through the intergeniculate leaflet (IGL) of the lateral geniculate nucleus, and finally, the geniculohypothalamic tract (GHT). Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is the neurotransmitter of the GHT. Serotoninergic (5-HT) input to the SCN arrives from the dorsal raphe nuclei. Melatonin, produced in the pineal gland, exerts its effect on circadian timing by feeding back onto the SCN.

Source: Reprinted with permission from reference 14Table 2

Suprachiasmatic nucleus dysfunction may have a role in schizophrenia

| Consequences of SCN dysfunction | Findings relevant to schizophrenia |

|---|---|

| Circadian pattern abnormalities | Individuals with schizophrenia do not have a characteristic circadian pattern of melatonin secretiona Actigraphic studies confirm that patients with schizophrenia have abnormal circadian rhythm activitiesb-d |

| Dopaminergic system abnormalities | The fetal dopaminergic system and D1 dopamine receptors may be involved in the process of synchronizing the SCNe,f |

| Jet lag symptomatology | Jet lag can exacerbate psychiatric disorders,g which suggests that in these patients the SCN is not capable of adjustment |

| Pathologic daytime sleep | Saccadic eye movements in patients with schizophrenia suggest they may be experiencing remnants of REM sleep, supporting the notion that these patients may have dream states during wakefulness |

| REM: rapid eye movement; SCN: suprachiasmatic nucleus | |

| Source: a. Bersani G, Mameli M, Garavini A, et al. Reduction of night/day difference in melatonin blood levels as a possible disease-related index in schizophrenia. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2003;24(3-4):181-184. b. Poyurovsky M, Nave R, Epstein R, et al. Actigraphic monitoring (actigraphy) of circadian locomotor activity in schizophrenic patients with acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;10(3):171-176. c. Haug HJ, Wirz-Justice A, Rössler W. Actigraphy to measure day structure as a therapeutic variable in the treatment of schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000;(407):91-95. d. Martin JL, Jeste DV, Ancoli-Israel S. Older schizophrenia patients have more disrupted sleep and circadian rhythms than age-matched comparison subjects. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(3):251-259. e. Strother WN, Norman AB, Lehman MN. D1-dopamine receptor binding and tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactivity in the fetal and neonatal hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;106(1-2):137-144. f. Viswanathan N, Weaver DR, Reppert SM, et al. Entrainment of the fetal hamster circadian pacemaker by prenatal injections of the dopamine agonist SKF 38393. J Neurosci. 1994;14(9):5393-5398. g. Katz G, Durst R, Zislin J, et al. Jet lag causing or exacerbating psychiatric disorders. Harefuah. 2000;138(10):809-812, 912. | |