Table 1

Psychiatric features associated with low cholesterol*

| Symptoms |

| Anxiety, depressed mood, emotional lability, euphoria, impulsivity, irritability, suicidal ideation, aggression |

| Syndromes |

| Anorexia nervosa, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, major depressive disorder, seasonal affective disorder |

| Behaviors |

| Suicide and suicide attempts, violence |

| *Small studies have suggested possible relationships with dissociative and panic disorders |

Effects of lipid-lowering agents

If there is a causal relationship between low cholesterol and mood disorders, then it stands to reason that using cholesterol-lowering drugs would increase the risk of depression and suicide. However, the data do not support that conclusion.

Many case reports have documented adverse psychiatric reactions to statins, including depression, suicidality, emotional lability, agitation, irritability, anxiety, panic, and euphoria.17 In an early analysis of primary prevention trials, patients receiving cholesterol-lowering treatment—mainly non-statins—were estimated to have twice the risk of death by suicide or violence compared with controls.3 However, a more recent meta-analysis of larger clinical trials of lipid-lowering agents including statins and observational studies did not reveal an association between lipid-lowering medications and suicide.15,18

In a large case-control study, statin users had a lower risk of depression (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.4, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.2 to 0.9) than patients taking non-statin lipid-lowering drugs (adjusted OR 1.0, 95% CI, 0.5 to 2.1).19 However, statins reduced cholesterol more (30% to 50%) than non-statin drugs (10% to 20%). A clinical trial of >1,000 patients with stable coronary artery disease treated with pravastatin—an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor with low lipophilicity that is less likely than other statins to cross the blood-brain barrier—revealed no changes in self-reported anger, impulsiveness, anxiety, or depression.20

This study did not exclude patients with psychiatric illness—who are at greatest risk of suicide—but other trials of lipid-lowering drugs did.21 As a result, the effects of lipid-lowering medications on psychiatric patients are unclear. A clinical trial is underway to assess the effects of pravastatin (low lipophilicity), simvastatin (high lipophilicity), or placebo on mood, sleep, and aggression.21

Low cholesterol: State or trait?

Much of the research linking low cholesterol, mood disorders, and suicidality could be confounded by depressed mood leading to reduced serum cholesterol. There has been considerable debate about whether low cholesterol predisposes patients to suicide or if depression independently leads to poor nutrition and therefore low cholesterol and increased suicide risk.6,22

Some researchers have suggested that depression lowers cholesterol and increases risk of suicide,23 but study designs have limited the ability to discern the directionality of the relationship. Attempts to control for depression-related malnutrition and weight loss—which lowers total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)24—suggest the association may be independent of these variables.25-27 These findings suggest that cholesterol may be considered a trait marker and is not entirely state-dependent. However, multiple, large, long-term randomized controlled trials have not shown increased depression and suicide with use of lipid-lowering agents in healthy populations.20

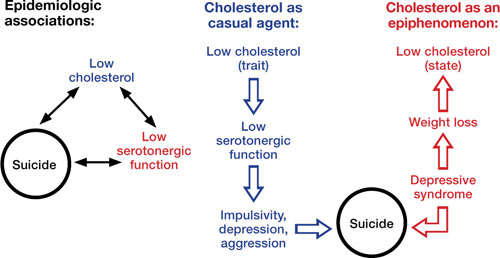

The Figure illustrates known epidemiologic associations of low cholesterol, low serotoninergic function, and suicide and contrasts conceptual models of cholesterol as a state and a trait marker. A case can be made for cholesterol as both a state and a trait marker, and these models could overlap, with depression-induced decreases in cholesterol further mediating changes in serotonergic function and related behavioral sequelae.

Figure

Cholesterol, depression, and suicide: How are they linked?

Low cholesterol may be considered a trait marker, predisposing patients to lower serotonergic function and placing them at greater risk for impulsivity, depression, aggression, and suicide. Other models suggest that lower cholesterol is a state-dependent consequence of depression, and not part of a causal chain toward suicide

Improving cardiac health

Limited epidemiologic studies suggest that patients with mood disorders may have lower levels of total cholesterol and LDL-C, but higher rates of hypertriglyceridemia compared with the general population.8 Unfortunately, psychiatric patients—who may be at increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease—may be less likely to be screened and appropriately treated for lipid abnormalities.28 To address this disparity, consider assuming an active role in assessing and managing hyperlipidemia in your patients with mood disorders. Be aware of your patients’ lipid profile and ensure that they follow monitoring recommendations.

The National Cholesterol Education Program recommends screening all adults age >20 for hyperlipidemia every 5 years using measures of total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides. If LDL-C or triglycerides exceed target values (Table 2), appropriate management includes recommending lifestyle changes and pharmacotherapy (Box 2).