Although clinicians and patients generally are cautious when prescribing or using antipsychotics during pregnancy, inadequately controlled psychiatric illness poses risks to both mother and child. Calculating the risks and benefits of antipsychotic use during pregnancy is limited by an incomplete understanding of the true effectiveness and full spectrum of risks of these medications. Ethical principles prohibit the type of rigorous research that would be needed to achieve clarity on this issue. This article reviews studies that might help guide clinicians who are considering prescribing an atypical antipsychotic to manage psychiatric illness in a pregnant woman.

Antipsychotic efficacy in pregnancy

All atypical antipsychotics available in the United States are FDA-approved for treating schizophrenia; some also have been approved for treating bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, or symptoms associated with autism (Table 1). Atypical antipsychotics frequently are used off-label for these and other categories of psychiatric illness, including unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

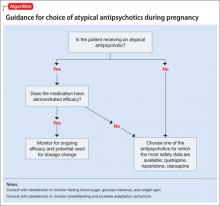

Studies of pharmacotherapy in pregnant women tend to focus more on safety rather than efficacy. Clinical decisions for an individual patient are best made based on knowledge about which medications have been effective for that patient in the past (Algorithm).

However, safety concerns in pregnancy may require modifying an existing regimen. In other cases, new symptoms arise during pregnancy and necessitate new medications. Additionally, a drug’s effectiveness may be affected by physiologic changes of pregnancy that can alter drug metabolism,1 potentially necessitating dose changes (Box 1).

Risks of treatment vs illness

Complete safety data on the use of any psychotropic medication during pregnancy are not available. To date, studies of atypical antipsychotics do not support any increased risk for congenital malformations large enough to be detected in medium-sized samples,2-4 although it is possible that there are increases in risk that are below the detection limit of these studies. Data regarding delivery outcomes are conflicting and difficult to interpret.

Several studies2-4 have yielded inconsistent results, including:

• risks for increased birth weight and large for gestational age3

• risks for low birth weight and small for gestational age2

• no significant differences from controls.4

Atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of gestational diabetes, whereas typical antipsychotics do not appear to increase this risk.4

Until recently, research has been limited by difficulties in separating the effects of treatment from the effects of psychiatric illness, which include intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, preterm birth, low Apgar scores, and congenital defects.5 In addition, most studies address early and easily measurable outcomes such as preterm labor, birth weight, and congenital malformations. Researchers are just beginning to investigate more subtle and long-term potential behavioral effects.

Several recent studies have explored outcomes associated with antipsychotic use during pregnancy while attempting to separate the effects of treatment from those of disease (Box 2).

Data on atypicals

Aripiprazole. Case reports of aripiprazole use during pregnancy have reported difficulties including transient unexplained fetal tachycardia that required emergent caesarean section6 and transient respiratory distress.7 Several small case series were not powered to detect risks related to aripiprazole.8,9

Animal data suggest teratogenic potential at dosages 3 and 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.10,11 Two studies7,12 that measured placental transfer of aripiprazole found cord-to-maternal serum concentration ratios ranging from 0.47 to 0.63, which is similar to the ratios for quetiapine and risperidone and lower than those for olanzapine and haloperidol.13

There are insufficient data to identify risks related to aripiprazole compared with other drugs in its class, and fewer reports are available than for other atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine and olanzapine. Placental transfer appears to be on the lower end of the spectrum for drugs in this class. Aripiprazole would be an acceptable choice for a woman who had a history of response to aripiprazole but likely would not be a first choice for a woman requiring a new medication during pregnancy.

Clozapine. In case reports, adverse effects associated with clozapine exposure during pregnancy include major malformations, gestational metabolic complications, poor pregnancy outcome, and perinatal adverse reactions. In one case, neonatal plasma clozapine concentrations were found to be twice that found in maternal plasma.14 Animal data have shown no evidence of increased teratogenicity at 2 to 4 times the maximum recommended human dosages.15 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with clozapine (11 exposures). Four other series2-4,16 were underpowered to detect concerns related specifically to clozapine.

There are insufficient data to identify risks related specifically to clozapine use during pregnancy. However, the rare but severe adverse effects associated with clozapine in other patient populations—including agranulocytosis and severe constipation17—could be devastating in a pregnant patient, which suggests this medication would not be a first-line treatment.