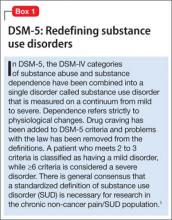

Patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) and a comorbid substance use disorder (SUD) are difficult to treat. There is a lack of high-quality clinical trials to guide management. This article focuses on current research, guidelines, and recommendations to best manage these patients. We present an analysis of recent statistics, patient characteristics, screening methods, as well as a discussion of changes to DSM-5 regarding substance abuse and addiction (Box 1).1

Opioid use and opioid-related overdoses have increased dramatically over the last decade (Box 2).2-5 Opioids are the primary medication used to treat CNCP, but their use in patients with comorbid SUDs is controversial. It is crucial for psychiatrists and other clinicians to know how to best identify, manage, and treat patients with CNCP/SUD.

Risk factors for CNCP/SUD

Evidence regarding the efficacy of screening methods to identify patients with chronic pain who are at high risk for substance misuse is insufficient. Key risk factors for developing chronic pain may include:

• elevated psychological distress

• negative beliefs and expectations about pain

• pain fear and avoidance

• disability

• anger or hostility

• maladaptive coping strategies

• catastrophic behaviors.5

In addition, these individuals may have a spouse who enables the sick role behavior.

Risk factors for developing a SUD related to prescribed opioids include:

• a history of problematic substance use

• sedative-hypnotic use

• positive family history for substance abuse

• legal problems

• heavy tobacco use

• age <50

• major depressive disorder or anxiety.5

In a review of 38 articles, Morasco et al6 found low-grade evidence with mixed results in attempt to find a correlation among sex, depression, anxiety, and tobacco use with CNCP/SUD. Other data suggest that the risk of addiction once opioids have been started increases with long refill periods and opioid morphine equivalents >120 mg.7 A history of childhood sexual abuse also may be a risk factor for chronic pain and addiction.5

Prevalence

The prevalence of opioid abuse among CNCP patients ranges from 3% to 48%; the highest rates are found among patients visiting the emergency room for opioid refills.7 These patients are more likely to exhibit aberrant behavior with their medications and may be prescribed higher opioid doses than patients who have CNCP only. Adherent CNCP/SUD patients show no difference in response to pain treatment compared with those with CNCP alone.6 Approximately 11.5% of CNCP patients taking opioids demonstrate aberrant medication use.6

Screening: Which method is best?

Data are scarce regarding the best screening methods to identify patients with CNCP/SUD. A survey of 48 patients by Moore et al8 found the combination of a clinical interview and the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) is 90% sensitive in detecting CNCP/SUD. However, a systematic review by Chou et al9 found only 2 well-designed studies showing that the SOAPP-R weakly predicts future aberrant drug behavior and only 1 study showed that a high risk categorization on the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) strongly increased the likelihood of predicting future abnormal drug-related behavior. Another well-designed study showed that the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) weakly raised the likelihood of detecting current aberrant drug behavior. No reliable data supported the efficacy of urine drug screens (UDS), pill counts, or prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) for improving clinical outcomes.9 In a systematic review Starrels et al10 found only low-quality evidence supporting the effectiveness of opioid agreement contracts and UDS.

Treatment strategies

Once a patient with CNCP/SUD has been identified, it is important to categorize the severity of his (her) pain and substance use by using the decision tree (Figure) and screening tools such as SOAPP-R, ORT, and COMM. In a Veterans Administration (VA) study, only 35% of patients with an SUD received substance abuse treatment.11 The 2009 American Pain Society/American Academy of Pain Medicine guidelines recommended that opioids should considered for patients with substance abuse, serious aberrant drug-related behaviors, or psychiatric comorbidities only if frequent monitoring and treatment plan and mental health or addiction consultation were in place.12 These guidelines also recommended discontinuing opioids if repeated atypical behavior, substance abuse, diversion, lack of progress, or intolerable side effects occur. Repeated and more serious behaviors require a multidisciplinary team, expert consultation, therapy restructuring, and possibly discontinuation of opioids.12

The U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy has created a council of federal agencies to spearhead the Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan, which includes 4 major categories to reduce prescription drug abuse: education, monitoring, proper disposal, and enforcement.13 FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg supports legislation to combine opioid education with Drug Enforcement Administration registration.14 The FDA began developing the risk evaluation and mitigation strategies in 2007 to educate physicians on proper prescribing of potentially dangerous medications.