MONTREAL – The brains of children who have been recently diagnosed with both epilepsy and anxiety are markedly different from those children who have seizures but are anxiety free, a study has shown.

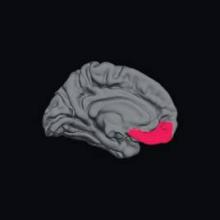

These differences include significantly larger left amygdala, and prefrontal cortices that are thinner in the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right front pole regions – a pattern known to be associated with anxiety and mood disorders in the general population.

Since these children have been diagnosed with epilepsy recently, — and thus have not had years of seizures – these findings may shed new light on the "chicken or egg" association of epilepsy and anxiety, Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., said at the 30th International Epilepsy Conference.

"Seizures are unpredictable, frightening, and are often viewed as a significant factor precipitating anxiety," said Dr. Jones of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "In contrast, these results suggest the presence of abnormal underlying neurobiology affecting subcortical and cortical regions implicated in anxiety in the general population."

She and her colleagues used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine brain structure in a cohort of 139 children aged 8-18 years: 25 with epilepsy and anxiety, 64 with epilepsy and no anxiety, and 50 healthy age-matched controls. The children’s average age was 13 years, with an average age of seizure onset of 12 years in those without anxiety and 11 years in those with anxiety. Most were taking one antiepileptic medication, but six in each group were not taking any. Two in the epilepsy/anxiety group were taking multiple antiepileptic medications.

In the epilepsy-only group, most (56%) had an idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome; 42% had a localization-related syndrome, and one was unclassified.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 68% had a localization-related syndrome and 32%, an idiopathic generalized syndrome.

All of the patients were assessed within 12 months of their epilepsy diagnosis. They all had a normal neurologic exam and a normal clinical MRI. They completed the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia questionnaire. The T1-weighted MRI scans were analyzed with the Free Surfer image analysis program.

In the epilepsy/anxiety group, 11 children had a specific phobia, 8 had separation anxiety disorder, 6 had a social phobia, 5 had generalized anxiety disorder, and 3 had an anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Eight children had a diagnosis of more than one anxiety disorder.

The control group had a significantly higher average IQ (108) than did the epileptic children with and without anxiety (99.8 and 101.4, respectively). Only 10% of the control subjects had academic problems – children with epilepsy had significantly more academic problems in both groups (44% in the epilepsy/anxiety group and 50% of the epilepsy-only group).

Structural brain measurements showed differences between the two patient groups, relative to the healthy control group. The children with epilepsy and anxiety had significantly larger left amygdala volume than did the epilepsy-only group.

Dr. Jones also found significant differences in cortical thickness in several key areas of the prefrontal cortex. In the epilepsy/anxiety group, the left medial orbital, right lateral orbital, and right frontal pole regions of cortex were significantly thinner than in the epilepsy-only group.

These observations support previous findings in children with disorders such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and phobias in the general population, and may be indicative of an abnormal system of emotion regulation involving top-down control of the amygdala via prefrontal cortical connections, Dr. Jones said in an interview.

Her group is currently examining this brain circuitry using diffusion tensor imaging, which allows researchers to image connective fibers in the brain. "Perhaps most importantly, these results suggest that it is important to recognize and treat anxiety early in the course of epilepsy, particularly because there is a relationship between anxiety in childhood leading to ongoing mental health issues in adulthood," she said.

Dr. Jana Jones said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal