Clinicians also need to consider the patient’s prognosis in their decision-making. For example, an extremely depressed or suicidal patient may not benefit from psychiatric hospitalization if she (he) has progressive neurovegetative symptoms and a prognosis of only a few weeks to live. These situations often are challenging and require a careful, informed discussion of the risks and benefits of all proposed interventions.

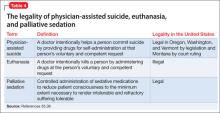

Clinicians also should be familiar with distinctions among ethical issues in end-of-life care, including physician-assisted suicide, euthanasia, and palliative sedation (Table 4).35,36

In Oregon, requests for physician-assisted suicide and hastened death through the state’s Death with Dignity Act often are short lived, and may not persist when clinicians offer patients good symptom management and psychological support.37 Requests for a hastened death often are motivated by loss of control, inability to find meaning in death, indignity from being dependent, and concern for future suffering and burden on loved ones.37

Carefully evaluate requests for hastened death in a manner that balances your personal and professional integrity. To preserve personal integrity, clearly communicate therapeutic interventions that you can and cannot provide. To ensure the patient does not feel abandoned, identify factors that contribute to the patient’s suffering and express a desire to search for alternative care approaches that will be mutually acceptable to the patient and to you.

Advance care planning and palliative care consultations may help in these circumstances. A randomized trial comparing advance care planning vs standard care in hospitalized geriatric patients found that advance care planning was more likely to lead to end-of-life wishes that were recognized by clinicians, and was associated with less distress, anxiety, and depression as reported by bereaved family members.38

Clinicians can assist patients with advanced care planning by helping them fill out advance directives, such as durable health care power of attorney documents and a living will. Palliative care clinicians can offer specialty-level assistance in advance care planning, provide focused assessments of physical and psychosocial symptoms, develop appropriate clinical goals, and assist in coordinating individualized care plans for seriously ill patients.2

Bottom Line

Depression commonly is encountered in hospice and palliative care patients and is associated with morbidity and distress. Validated screening tools can help you distinguish major depressive disorder from depressive symptoms in this population. Several psychotherapeutic techniques have been shown to be beneficial. In addition to traditional antidepressants, psychostimulants or ketamine may help address acute depressive symptoms in patients who have days or weeks to live.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www.aahpm.org.

- Death with Dignity National Center. www.deathwithdignity.org.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. www.nhpco.org.

- Oregon Health Authority. Death with Dignity Act. http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evaluationresearch/deathwithdignityact/Pages/index.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Modafinil • Provigil

Ketamine • Ketalar Selegiline (transdermal) • EMSAM

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin Mirtazipine • Remeron

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.