HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – A manualized psychosocial intervention known as customized adherence enhancement coupled with long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication produced marked improvement in adherence to concomitant oral medication as well as in psychiatric symptoms and functional status in urban homeless people with schizophrenia in a small prospective observational study.

Moreover, the intervention also achieved an impressive improvement in a domain not often considered in psychiatric studies, but one of great practical value to patients and their families: housing conditions, Dr. Martha Sajatovic said at a meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health

The mean time spent in suboptimal housing – living outdoors or in jail – changed from 56% during the 6 months prior to study enrollment to 41% in the first 3 months of the intervention and a mere 14% in the second 3 months of the study, reported Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

"What I think is most interesting about our study are the housing data. Our intervention did not include anything about housing – no housing placement or outreach or anything like that. People used whatever was available in the community. And Cleveland has the dubious distinction of being one of the poorest cities in America, so we have services, but not a lot of them," she noted.

Customized adherence enhancement (CAE) is a needs-based, flexibly dosed psychosocial intervention originally developed by Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues to improve medication adherence in individuals with bipolar disorder receiving antipsychotic therapy. Following a 6-month study demonstrating its benefits in this population (Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:291-300), the investigators adapted the manualized CAE program for application in a particularly challenging patient population: homeless people with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and poor adherence to their prescribed oral antipsychotic medication.

This 6-month, observational, uncontrolled study involved 30 homeless schizophrenic patients. The CAE consisted of once-monthly brief interventions matched to core adherence vulnerabilities identified at baseline. The CAE entailed psychoeducation, modified motivational enhancement therapy, and coaching on communication with providers and medication routines.

At the time of the monthly CAE session, patients also received a dose of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication. Because the study was funded by a small nonprofit charitable organization, investigators employed the least expensive long-acting antipsychotic available: intramuscular haloperidol decanoate. This resulted in a high rate of side effects, most prominently restlessness because of akathisia in 40% of subjects, dry mouth in 33%, and muscle twitching in 33%. The mean monthly dose at 24 weeks was 68 mg, with a range of 50-100 mg.

The study population was typical of homeless individuals with major mental illness. Their mean age was 42 years, roughly half were women, 97% had a history of substance abuse, 97% had a history of incarceration, most subjects had not finished high school, and 70% were single or never married.

All patients remained on oral medication in addition to their new long-acting injectable antipsychotic regimen. Adherence to oral medication improved dramatically during the 6-month intervention: At baseline, patients had missed 46% of their oral medication during the past month, compared with just 10% at week 25. Adherence to long-acting injectable therapy was good: 76% at 6 months.

Twenty of 30 patients completed the 6-month study. Of the 10 nonfinishers, 3 were incarcerated, 2 relocated elsewhere, 1 discontinued because of drug-induced akathisia, and 4 were lost to follow-up.

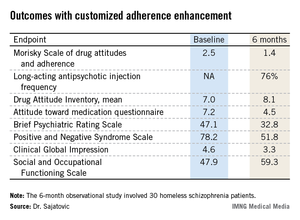

Participants showed significant improvement in numerous measures of adherence behavior, treatment attitudes, psychiatric symptoms, and functioning (see chart).

For Dr. Sajatovic, the take-home message from this study was clear: "I would say that when we think about adherence, we can talk about relapse, but it’s very hard to have relapse as an outcome measure in these kinds of patients. They start out in relapse. So we should also consider those outcome components that patients and families really value, like functioning and housing."

Discussant Dr. Stephen R. Marder concurred: "Adherence is not necessarily the goal; it’s the path to better outcomes. And looking at things that are distal to relapse and symptoms – things like housing – shows an advantage. We need to tell patients that preventing relapse is just one of the reasons to be adherent. Long-term outcomes, whether it’s housing, work, school, or independent living, seem to be better for people who are adherent to medication. With adherence, rehabilitation can start.

"Without adherence, it’s really impossible to do," commented Dr. Marder, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of the section on psychosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute.