When Kanner first described autism,1 the disorder was believed to be an uncommon condition, occurring in 4 of every 10,000 children. Over the past few years, however, the rate of autism has increased substantially. Autism is now regarded as a childhood-onset spectrum disordera characterized by persistent deficits in social communication, with a restricted pattern of interests and activities, occurring in approximately 1% of children.3

In DSM-IV-TR, Asperger’s disorder (AD), first described as “autistic psychopathy,”4 is categorized as a subtype of ASD in which the patient, without a history of language delay or mental retardation, has autistic social deficits that do not meet full criteria for autism.

DSM-5 eliminated AD as an independent category, including it instead as part of ASD.5 The label “high-functioning autism” is sometimes used to refer to persons with autism who have normal intelligence (usually defined as full-scale IQ >70), whereas those who have severe intellectual and communication disability are referred to as “low-functioning.” I use “high-functioning autism” and “Asperger’s disorder” interchangeably.

Violent crime and ASD/AD

Reports in the past 2 decades have described violent behavior in persons with ASD/AD. Because of the sensational and unusual nature of these criminal incidents, there is a perception by the public that persons with these disorders, especially those with AD, are predisposed to violent behavior. (Incidents allegedly committed by persons with ASD include the 2007 Virginia Tech campus shooting and the 2012 Newtown, Connecticut, school massacre.6)

Yet neither the original descriptions by Kanner (of autism) and Asperger, nor follow-up studies based on the initial samples studied, showed an increased prevalence of violent crime among persons with ASD/AD.7

In this article, I examine the evidence behind the claim that people who have ASD/AD are predisposed to criminal violence. At the conclusion, you should, as a physician without special training in autism, have a better understanding of when to suspect ASD/AD in an adult who is involved in criminal behavior.

When should you suspect ASD/AD in an adult?

Although autism is a childhood-onset disorder, its symptoms persist across the life

span. If the diagnosis is missed in childhood, which is likely to happen if the person has normal intelligence and relatively good verbal skills, he (she) might come to medical attention for the first time as an adult.

Because most psychiatrists who treat adults do not receive adequate training in the assessment of childhood psychiatric disorders, ASD/AD might be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. What clues help identify underlying ASD/AD when a patient is referred to you for psychiatric evaluation after allegedly committing a violent crime?

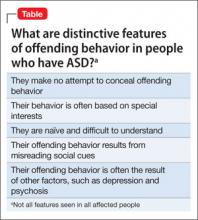

Clue #1. He makes no attempt to deny or conceal the act. The behavior appears to be part of ritualistic behavior or excessive interest (Table).

Often, the alleged crime occurs when the patient’s excessive interests “get out of control,” perhaps because of an external event. For example, a teenager with AD who is fixated on video games might stumble upon pornographic web sites and begin making obscene telephone calls. Particular attention should be paid to a history of rigid, restricted interests beginning in early childhood.

These restricted interests change over time and correlate with intelligence level: The higher the level of intelligence, the more sophisticated the level of fixation. Examples of fixations include computers, technology, and scientific experiments and pursuits. Repeated acts of arson have been reported to be part of an autistic person’s fixation with starting fires.8

Clue #2. He appears to lack sound and prudent judgment despite normal intelligence.

Although most patients with ASD score in the intellectually disabled or mentally retarded range, at least one-third have an IQ in the normal range.9 Examine school records and reports from other agencies when evaluating a patient. Pay attention to a history of difficulty relating to peers at an early age, combined with evidence of rigid, restricted fixations and interests.

It is important to obtain a reliable history going back to early childhood, and not rely just on the patient’s mental status; presenting symptoms might mask underlying traits of ASD, especially in higher-functioning adults. (I once cared for a young man with ASD who had been fired a few days after landing his first job selling used cars because he was “sexually harassing” his colleagues. When questioned, he said that he was only trying to be “friendly” and “practicing his social skills.”)

Clue #3. He has been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia without a clear history of hallucinations or delusions.

Differentiating chronic schizophrenia and autism in adults is not always easy, especially in those who have an intellectual disability. In patients whose cognitive and verbal skills are relatively well preserved (such as AD), the presence of intense, focused interests, a pedantic manner of speaking, and abnormalities of nonverbal communication can help clarify the diagnosis. In particular, a recorded history of “childhood schizophrenia” or “obsessive-compulsive behavior” going back to preschool years should alert you to possible ASD.