Red flags flying

Mr. K’s case highlights several red flags that should raise suspicion of malingering (Table 1)3,4:

- A conditional statement by which a patient threatens to harm himself or others, contingent upon a demand—for example, “If I don’t get A, I’ll do B.”

- An overly dramatic presentation, in which the patient is quick to endorse

distressing symptoms. Consider Mr. K: He was quick to report that he saw Big Bird, and that this Sesame Street character “was 100 feet tall.” Patients who have been experiencing true psychotic symptoms might be reluctant to speak of their distressing symptoms, especially if they have not experienced such symptoms in the past (the first psychotic break). Mr. K, however, volunteered and called attention to particularly dramatic psychotic symptoms. - A subjective report of distress that is inconsistent with the objective presentation. Mr. K’s report of depression—a diagnosis that typically includes insomnia and poor appetite—was inconsistent with his behavior: He slept and he ate all of his meals.

Atypical (vs typical) psychosis

Malingering can occur in various arenas and take many different forms. In forensic settings, such as prison, malingered conditions more often present as posttraumatic stress disorder or cognitive impairment.5 In non-forensic settings, such as the ER, the most commonly malingered conditions include suicidality and psychosis.

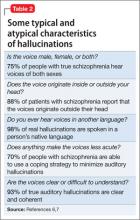

To detect malingered psychosis, one must first understand how true psychotic symptoms manifest. The following discussion describes and compares typical and atypical symptoms of psychosis; examples are given in Table 2.6,7No single atypical psychotic symptom is indicative of malingering. Rather, a collection of atypical symptoms, when considered in clinical context, should raise suspicion of malingering and prompt you to seek additional collateral information or perform appropriate testing for malingering.

Hallucinations

Typically, hallucinations take three forms: auditory, visual, and tactile. In primary psychiatric conditions, auditory hallucinations are the most common of those three.

Tactile hallucinations can be present during episodes of substance intoxication or withdrawal (eg, so-called coke bugs).

Auditory hallucinations. Patients who malinger psychosis are often unaware of the nuances of hallucinations. For example, they might report the atypical symptom of continuous voices; in fact, most patients who have schizophrenia hear voices intermittently. Keep in mind, too, that 75% of patients who have schizophrenia hear male and female voices, and that 70% have some type of coping strategy to minimize their internal stimuli (eg, listening to music).6,7

Visual hallucinations are most often associated with neurologic disease, but also occur often in primary psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia.

Patients who malinger psychotic symptoms often are open to suggestion, and are quick to endorse visual hallucinations. When asked to describe their hallucinations, however, they often respond without details (“I don’t know”). Other times, they overcompensate with wild exaggeration of atypical visions—recall Mr. K’s description of a towering Big Bird. Asked if the visions are in black and white, they might eagerly agree. Research suggests, however, that patients who have schizophrenia more often experience life-sized hallucinations of vivid scenes with family members, religious figures, or animals.8 Furthermore, genuine visual hallucinations typically are in color.

Putting malingering in the differential

Regardless of the number of atypical symptoms a patient exhibits, malingering will be missed if you do not include it in the differential diagnosis. This fact was made evident in a 1973 study.9

In that study, Rosenhan and seven of his colleagues—a psychology graduate student, three psychologists, a pediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter, and a housewife—presented to various ERs and intake units, and, as they had been instructed, endorsed vague auditory hallucinations of “empty,” “hollow,” or “thud” sounds—but nothing more. All were admitted to psychiatric hospitals. Once admitted, they refrained (again, as instructed) from endorsing or exhibiting any psychotic symptoms.

Despite the vague nature of the reported auditory hallucinations and how rapidly symptoms resolved on admission, seven of these pseudo-patients were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and one was given a diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis. Duration of admission ranged from 7 to 52 days (average, 19 days). None of the study participants were suspected of feigning symptoms.

It’s fortunate that, since then, mental health professionals have developed more structured techniques of assessment to detect malingering in inpatient and triage settings.

Testing to identify and assess malingering

The ER is a fast-paced environment, in which treatment teams are challenged to make rapid clinical assessments. With the overwhelming number of patients seeking mental health care in the ER, however, overall wait times are increasing; in some regions, it is common to write, then to rewrite, involuntary psychiatric holds for patients awaiting transfer to a psychiatric hospital. This extended duration presents an opportunity to serially evaluate patients suspected of malingering.