ORLANDO – Prescribing of three or more psychotropic medications has increased among foster children enrolled in Medicaid, based on an analysis of claims data in Ohio. The findings of polypharmacy are raising red flags about oversight and monitoring of psychotropic medication use among high-risk youth.

By 2008, nearly a quarter of foster care and disabled children in the Ohio Medicaid program were prescribed three or more psychiatric medications. Nearly one-fifth of them were prescribed medications from three or more drug classes, with the most common combination being stimulants, antipsychotics, and alpha-agonists.

The findings make a powerful case for system-wide oversight and monitoring of psychotropic prescribing practices in the Medicaid population, especially for children in foster care, said Cynthia A. Fontanella, Ph.D., of the Ohio State University, Columbus, who led the study and presented her findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. "We don’t know if these kids are doing better ... The increase has "occurred despite lack of data on safety and efficacy of multiple drug combination and existing concerns about adverse effects of drug-drug interactions."

A 2012 report by the Government Accountability Office that showed 18% of foster children were taking psychotropic medications. That report additionally noted, however, that 30% of the children who may have needed mental health services hadn't received them.

The rising rates of polypharmacy, especially in children enrolled in Medicaid, have been documented in other studies. But the accumulating data implies polypharmacy is pervasive in at-risk children. "It’s a growing trend," said Susan dosReis, Ph.D., associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, who has studied psychiatric prescription patterns among youth. She was not involved in the study.

Dr. dosReis acknowledged that the issue is complex, especially in the cases of children with severe conditions. Clinicians face families who are looking for a way to manage their child or to keep them in school. "And once you have a child on a combination, and there’s improvement, the thought of taking away the medications is hard to accept, because [the family is] afraid that the condition will worsen again."

Also, follow-up has been problematic, with data that don’t clearly indicate whether the children were on several medications for a short period of time until they were stabilized, or the whether the polypharmacy lasted longer. Data for children enrolled in private insurance are lacking, and prescribing is difficult to track for children in foster care because they move frequently.

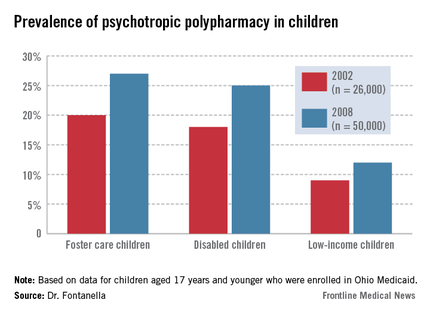

Dr. Fontanella and her colleagues compared polypharmacy patterns and rates in foster care, disabled, and low-income youth aged 17 years and younger enrolled in Ohio Medicaid between 2002 (n = 26,000) and 2008 (n = 50,000).

The two outcome measures — any polypharmacy (three or more medications) — and multiclass polypharmacy (three or more medications from different drug classes) increased over time across all three groups. Polypharmacy increased from 9% to 12% for low-income youth; from 18% to 25% in disabled youth; and from 20% to 27% in foster care youth.

Combination therapies that increased the most during the time of the study were prescriptions of two or more antipsychotics, two or more stimulants, and antipsychotics with stimulants and other psychotropic medications excluding antidepressants.

The percentage of foster children who were prescribed two or more antipsychotics increased from 5% in 2002 to 10% in 2008, compared with 6% to 9% among children with disabilities, and 3% to 5% among low-income children.

The percentage of foster children who were prescribed two or more stimulants also showed a bigger jump – from 1.5% in 2002 to 8% in 2008 – compared with 1.5% to 6% among children with disabilities, and 3% to 7% among low-income children.

Meanwhile, multiclass polypharmacy has been increasing over the years, from 14% during 1996-1999 to 20% during 2004-2007. Even when it’s indicated, polypharmacy increases the risk for adverse events and drug-drug interactions, creates a complicated drug regimen and the need for more medication, and leads to higher costs, the researchers said.

Researchers also found some within class and between-class prescribing trends.

While the prescription rates for two or more antipsychotics and stimulants increased, the rate of combination antidepressant prescribing decreased.

It’s not clear if the findings can be generalized to other states and to non-Medicaid populations, the researchers noted. Also, a 30-day window as a measure of prevalence may lead to overestimation of polypharmacy, and, prescriptions don’t necessarily translate to adherence.