CASE Paranoid and hallucinating

Ms. S, age 30, is an unmarried graduate student who has been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, paranoid type, during inpatient hospitalization that was prompted by impairment in school functioning (difficulty turning in assignments, poor concentration, making careless mistakes on tests), paranoid delusions, and multisensory hallucinations. She says that her roommate and classmates are working together to make her leave school, and recalls seeing them “snare and smirk” as she passes by. Ms. S says that she feels her classmates are calling her names and talking badly about her as soon as she is out of sight.

Ms. S is antipsychotic-naïve and has a baseline body mass index of 17.8 kg/m2, indicating that she is underweight. We believe that olanzapine, 20 mg/d, is a good initial treatment because of its propensity for weight gain; however, she experiences only marginal improvement. Ms. S does not have health insurance, and cannot afford a brand name medication; therefore, she is cross-tapered to perphenazine, 8 mg, and benzatropine, 0.5 mg, both taken twice daily (olanzapine was not available as a generic at the time).

At discharge, Ms. S does not report any hallucinatory experiences, but is guarded, voices suspicions about the treatment team, and asks “What are they doing with all my blood?”—referring to blood draws for laboratory testing during hospitalization.

As an outpatient, Ms. S is continued on the same medications until she has to be switched because she cannot afford the out-of-pocket cost of the antipsychotic, perphenazine ($80 a month). Clozapine is recommended, but Ms. S refuses because of the mandatory weekly blood monitoring. She briefly tries fluphenazine, 2.5 mg/d, but it is discontinued because of malaise and lightheadedness without extrapyramidal symptoms.

Clozapine is again recommended, but Ms. S remains suspicious of the necessary blood draws and refuses. After several trials of antipsychotics, Ms. S starts paliperidone using samples from the clinic, titrated to 6 mg at bedtime. Once tolerance and therapeutic improvement are observed, she is continued on this medication through the manufacturer’s patient assistance program.

Within 3 months, Ms. S and her family find that she has improved significantly. She no longer reports hallucinatory experiences, is less guarded during sessions, and has followed through with paid and volunteer job applications and interviews. She soon finds a job teaching entry-level classes at a community college and is looking forward to a summer trip abroad.

During a follow-up appointment, Ms. S reports that she had missed 2 consecutive menstrual cycles without galactorrhea or fractures. A urine pregnancy test is negative; the prolactin level is 72 μg/L.

Hyperprolactinemia in women is defined as a plasma prolactin level of

a)>2.5 µg/L

b) >5 µg/L

c) >10 µg/L

d) >20 µg/L

e) >25 µg/L

The authors’ observations

A prolactin level >25 μg/L is considered abnormal.1 A level of >250 μg/L may identify a prolactinoma; however, levels >200 μg/L have been observed in patients taking an antipsychotic.1 Given Ms. S’s clinically significant elevation of prolactin, she is referred to her primary care physician. We decide to augment her regimen with aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, because this drug has been noted to help in cases of hyperprolactinemia associated with other antipsychotics.2,3

Prolactin serves several roles in the body, including but not limited to lactation, sexual gratification, proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells, surfactant synthesis of fetal lungs at the end of pregnancy, and neurogenesis in maternal and fetal brains (Figure 1 and Figure 2). A 2004 review reported secondary amenorrhea, galactorrhea, and osteopenia as common symptoms of hyperprolactinemia.5 Hyperprolactinemia has been seen with most antipsychotics, both typical and atypical. Although several studies document prolactin elevation with risperidone, fewer have examined the active metabolite (9-hydroxyrisperidone) paliperidone.5-7

In women, a high prolactin level can cause

a) menstrual disturbance

b) galactorrhea

c) breast engorgement

d) sexual dysfunction

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

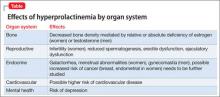

Acutely, hyperprolactinemia can cause menstrual abnormalities, decreased libido, breast engorgement, galactorrhea, and sexual dysfunction in women.8 In men, the most common symptoms of hyperprolactinemia are loss of interest in sex, erectile dysfunction, infertility, and gynecomastia. Osteoporosis has been associated with chronic elevation of the prolactin level8 (Table).

TREATMENT Adjunctive aripiprazole

After 8 weeks of adjunctive aripiprazole, Ms. S’s prolactin level decreases to 42 μg/L, but menses do not return. Because her family and primary care providers are eager to have the prolactin level return to normal, reducing her risk of complications, we decide to decrease paliperidone to 3 mg at bedtime.

Eight weeks later, Ms. S shows functional improvement. A repeat test of prolactin is 24 μg/L; she reports a 4-day period of spotting 1 week ago. One month later, the prolactin level is 21 μg/L, and she reports having a normal menstrual period. She continues treatment with paliperidone, 3 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, experiences regular menses, and continues teaching.

Pharmacotherapy of hyperprolactinemia includes