Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

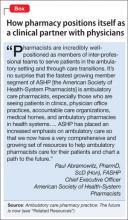

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.