Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

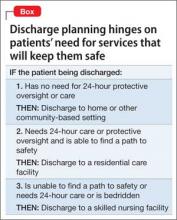

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility